Psychiatric residential treatment facilities: the struggle to get care

Kaia was just a scared 13-year-old girl the first time she was admitted to Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital for anorexia and self harm. She was compliant with her treatment — eating everything she was instructed to — and wanted to get better.

Kaia was admitted to Yale twice. They recommended a residential facility to her family so she could continue inpatient treatment.

“It was the worst decision we could have possibly have made,” her mother Gina said. “Why would you take a girl who has never been to any program or had extensive therapy and put her into an inpatient facility where she’s seeing 16 and 17 year olds on [feeding] tubes?”

That was the start of Kaia’s two-year, nationwide journey through residential treatment programs. Since then, Kaia has visited at least 10 facilities across the U.S. in hopes of receiving care. When she could not find long-term placement in her home state of Connecticut, Gina tried sending her daughter to other facilities in Massachusetts, Chicago, Denver, Arizona — all the way to Hawaii.

None were able to effectively care for Kaia. Gina said every facility kicked Kaia out for not eating, self harming or not having the capacity to put her on a feeding tube.

“I feel almost numb from it all now,” Gina said.

Kaia’s anorexia was greatly influenced by her home circumstances. With divorced parents, Gina said the back-and-forth pushed her eating disorder to the level of needing care at Yale. Although Gina believes the family connection plays a key role in treating eating disorders and family-based therapy is crucial, Kaia’s home was simply not the best option for her to recover.

The first facility Kaia visited was just south of Boston. It was the only one that admitted her under her father’s HUSKY care, Connecticut’s public insurance. Gina described it as “one of the worst places for anybody, most likely because it’s on public insurance.”

“After that, I switched her to private insurance,” Gina said. “And then everything kind of opened up for her.”

With each facility Kaia attended, Gina found there was a certain philosophy surrounding treatment of eating disorders: the body and mind are too starved to deal with the issues causing the problem.

“I can honestly say in the two years that Kaia was in and out of treatment centers, she probably got less therapy than she would have if she had done two weekly sessions,” Gina said. “That’s why I say it’s more of like a holding space, because they don’t try to dive into the root, core causes.”

Gina said Backcountry Wellness in Greenwich, Conn., was the best program Kaia was in, with a small bed size of about 10 and higher standards of care. While Backcountry is in-network with multiple insurance providers, Gina commented that the facility takes a lot of private care or out of network exceptions.

While Kaia struggled with anorexia, she also self-harmed. Gina said that in facilities geared towards eating disorders, Kaia was kicked out for self-harm incidents. If she was admitted to another facility for self-harm, she would stop eating. It seemed as if no facility could appropriately care for her needs, even though eating disorders are a form of self-harm and often go hand-in-hand with one another.

During one eight-month period, Kaia did not put a single piece of food in her mouth.

She was in this limbo space quite often of nobody wanting her. It was kind of this cycle of not being able to actually get her the help that she needed.

— Gina

When Kaia did not eat in a facility, Gina recalls certain privileges were taken away; Kaia was not allowed to go outside with other residents or participate in activities.

“It’s like punishing you for the reason that you’re there,” Gina said. “They’re not privileges, they’re what makes people happy and healthy. It’s going outside.”

Gina said almost every facility operated this way. The only one that did not — the second-best program Kaia attended — was Ai Pono in Hawaii. In a small house near the beach, Kaia was able to freely go inside and out.

Ai Pono was also the only program that combined both youth and adults, which Kaia found to be helpful. In adolescent programs, a sense of competition can kick in to see who can be the ‘worst’ in a group. But with the adults, Kaia said they at least wanted to recover a bit more, serving as more positive role models for younger residents.

Kaia has borderline personality traits, which can result in wanting to be absorbed by whatever is around her. When she has positive influences, this can go a long way. But in many of these facilities, where there is a lot of time spent in group therapy, she was learning behaviors she did not exhibit before.

Gina recalls when Kaia was at the Center for Discovery in Arizona, she began purging and expressing suicidal ideations, neither of which were part of her diagnosis. By connecting with other parents through blogs, Gina found that Kaia’s behaviors were mirroring another girl’s in the facility.

The last facility Kaia attended was the Eating Recovery Center (ERC) in Denver. Gina said the facility was supposed to be one of the best in the country, but that was far from her and Kaia’s experience.

They are not alone. In recent months, the facility has been called out twice for punitive treatment and ignoring repeated suicide attempts.

With a strong emphasis on family therapy, ERC asked Gina to move out to Denver during the time of Kaia’s treatment. Gina said she would just sit in a room with her daughter and do the feeding herself, alone. When Kaia was no longer eating, they asked Gina to stop coming in and no longer utilized her, even though she went across the country to support her daughter per the facility’s request.

The facility was so understaffed on the weekends, Kaia knew they could not properly care for her.

“They couldn’t hold her down and restrain her and force feed the tube, which at points that’s what was needed so she wouldn’t die,” Gina said.

She would starve herself to the point of no food, no water, that she would end up in the hospital every weekend because they couldn’t give her the care that she needed.

— Gina

Kaia was eventually kicked out of ERC because Gina “traveled too much.” But Gina thinks it was because Kaia had a significant self-harm incident, and the facility was afraid of the liability.

ERC told Gina that Kaia was able to lock herself in her room and self-harm. Gina said there was no “locking herself in her room.”

“All she did was go in her room, but somehow she cut her arm 30 times and needed stitches,” Gina said. “They booted her out without any place to go, without any protocol. They just kicked her out.”

It was not the first time Gina experienced this when Kaia was discharged from a facility.

“They just say good luck and I’m scrambling trying to find the next place for her,” she said.

***

Across the country, youth are trying to get help for their psychiatric or behavioral health needs. Placed in treatment centers, therapeutic boarding schools or other programs that claim to provide rehabilitation, adolescents are sometimes traumatized even further by the care they are supposed to be receiving.

Their accounts are harrowing — so much so, the bipartisan Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act was introduced in Congress in April 2023. The goal of this bill is to increase oversight and transparency of institutional treatment facilities, with more robust communication between states for best practices and care and preventing abuse.

“Right now, over 100,000 children are at risk of abuse, neglect, and even death due to a complete lack of transparency in the so-called ‘troubled-teen industry,’” said California Congressman Ro Khanna in a statement about the proposed legislation. “We cannot allow this to continue.”

Ava was adopted by a single mom when she was 11 months old. She is diagnosed with autism and an intellectual disability.

By the time she was 13, Ava had broken mirrors and chased caregivers with the shards. She pulled her sister’s hair out to the point of bleeding and had a hole in her bedroom door.

After alternative schools turned her away and multiple hospital visits, Ava made her way to Albert J. Solnit Center in Hartford, Conn. for two weeks before they attempted to discharge her. Her mother did not think it was safe for Ava to leave and refused to pick her up.

Eventually, Solnit cared for her for about five months.

Read more about Ava's story from Connecticut Public Radio.

Amari was 11 months old when her 18-year-old mother handed her over to an aunt to be cared for. She was prescribed ADHD medication at 4 years old and worked with social workers and therapists through her pre-teen years, struggling with feelings of abandonment and coping mechanisms for social skills.

At 10 years old, her biological mother stopped returning her calls. That same spring of 2019, Amari told her aunt she was molested by a cousin’s boyfriend.

When she was 11, Amari told clinicians a “bad emoji” would tell her to run out into the street or jump out of cars. She also threatened to stab her babysitter with a knife.

It took months for Amari to be admitted into a psychiatric program near her home in Rochester, N.Y. It took even longer for her to be placed in a more appropriate intensive residential program. She was out of her home for over two years.

Read more about Amari's story from ProPublica.

M, who goes by their first initial, watched his father abuse his mother growing up on Long Island. After his parents split, he became violent with his mother, to the point of threatening to kill her. At 12 years old, he was admitted into a group home.

When he was 16, M's mother and family advocates submitted applications for him to be admitted into a residential treatment facility, with an intensive care level he notably needed. His providers said treatment was urgent — he needed it before he became an adult.

Unfortunately, M aged out of the system. He moved into an adult housing program, but can be kicked out for disruptive behavior. If that happens, he would be sent to a homeless shelter. Or, he could possibly end up in prison.

Read more about M's story from ProPublica.

The New York tri-state area is no different. Adolescents are struggling to receive mental health care in Connecticut, New York and New Jersey, whether from admission difficulties, rising healthcare costs or an overall lack of adequate treatment in residential facilities.

Since 2000, states have decreased the number of youth in residential care, closing facilities in each state and moving minors to more outpatient and community-centered care models.

For youth in underserved communities, options can be even more limited. If youth cannot find bed placements or some sort of effective care, families often have to pay for frequent hospitalizations, various medications or other outpatient services to keep their child stabilized.

And for families, facilities and state agencies, residential care can be an extensive cost.

For Kaia, when she was kicked out for the last time, Gina put together her own team of sorts for Kaia’s treatment. She finally turned a corner.

Gina worked on eating with Kaia at home and was able to get her back on track with her eating. Within two weeks, Kaia gained about eight pounds. Gina credits some of this to a friend Kaia made at ERC who was a positive influence on her, struggling with many of the same issues.

Now, at almost 16 years old, Kaia is enrolled in a therapeutic boarding school in New Hampshire. She gets all A’s in her classes — despite receiving little to no education during her years of residential treatment — and is mostly able to be on her own.

Although her school district offered tutoring when she first began her treatment, she did not receive much while moving around to different facilities or at the severity of her state.

“They did some schooling here and there in the facilities, but not really,” Gina said. “She just happens to be an avid reader, so she must have read like 20 books in those two years.”

Gina thinks the systems in place seem as if they are unsure of how to care for the youth in their care.

“I feel like none of them have figured out or even have a clue on the right path or the right way to go about dealing with eating disorders,” she said. Kaia was put on drugs like ketamine and lithium, some of which helped her eat after a certain point, but did not provide any long-term solutions.

“She’s been on everything under the sun and nothing has helped her,” Gina said. “They even wanted to do electric shock therapy on her.”

Kaia recently had a flare up last month that brought Gina to New Hampshire to help her finish the semester, but overall she is doing significantly better than before. She visited her friend from ERC over Thanksgiving weekend in California and is close to completing the semester at school.

Gina says the residential care was necessary in some ways for Kaia to be outside of her home situation and see things differently, but ultimately would not recommend residential treatment to families in similar situations to hers.

“She’s lost two years of her life,” she said.

Residential treatment facilities underwent changes in the late 1990s, as Connecticut began to provide more treatment for youth in a subacute level of care. Following psychiatric hospitalizations, youth required more intensive care in structured settings with higher supervision.

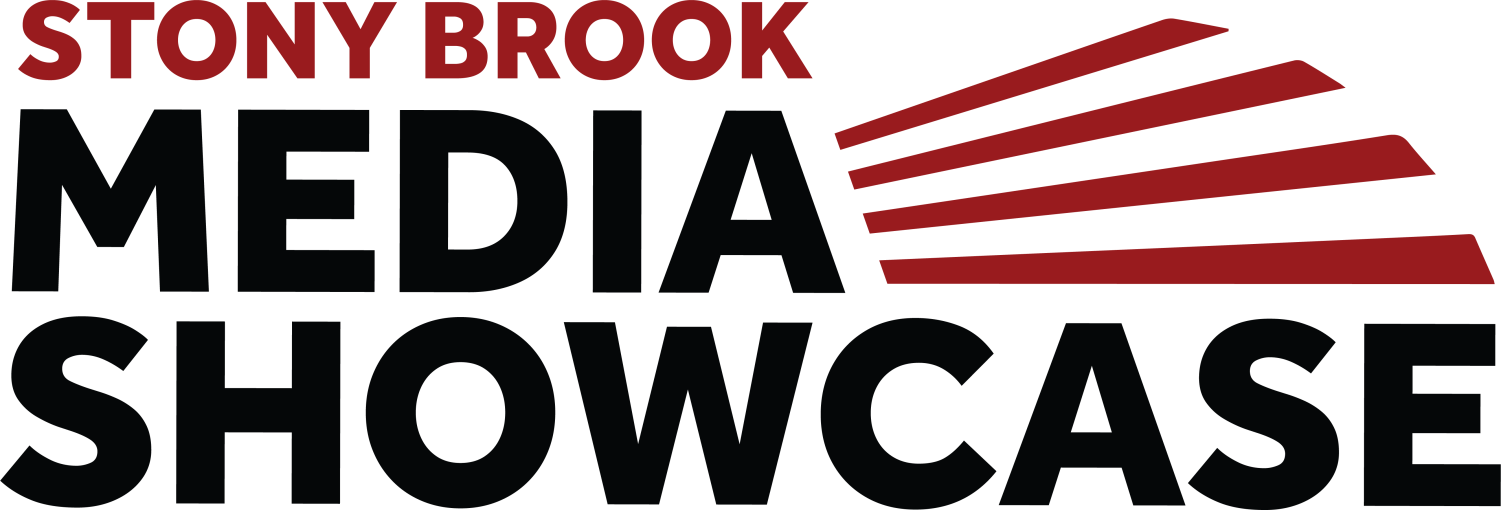

The Department of Children and Families (DCF) licenses five different types of Child Caring Facilities, defined as congregate residential settings for out-of-home placement of children or youth under age 18. These facilities are classified as: group homes, residential treatment centers, residential education facilities, temporary shelters and Short Term Assessment and Respite Home (STAR) homes.

Residential treatment centers (RTC) meet long-term placement needs. Clinical treatment is provided on-site, in a therapeutic setting, for psychiatric, behavioral and emotional disorders. Medical care is provided by nurses on site, child care staff, community-based medical professionals or hospitals.

These differ from therapeutic group homes, which are designed to serve children with significant behavioral health or developmental issues. Clinical services are provided by licensed mental health professionals, with monitoring of psychotropic medications on-site by a psychiatrist. Limited nursing services are provided with community-based medical services.

An October report from the Office of the Child Advocate, an independent oversight agency, was released following a story from CT Inside Investigator that described serious incidents at a Harwinton STAR home, which prompted visits from law enforcement and emergency medical services. Concerns were raised about young girls at risk of domestic sex trafficking, behaviors of the adult staff towards youth, fighting and frequent runaways.

The report said that over the past 12 years, Connecticut has “dramatically reduced capacity in residential treatment settings.” Providers and advocates worry that the state did not appropriately reinvest in 24/7 treatment settings to replace the old residential models, resulting in struggles to receive timely access to effective care.

The state currently operates or licenses five psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTFs) that provide subacute care to youth. The OCA report found the average wait for adolescent girls to be admitted into these facilities is over three months.

Even for in-home care, the waitlist for Intensive In-Home Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services is typically about 400-500 families. OCA reported that each level of care has been impacted by workforce shortages and staffing challenges.

“The decades-long underfunding of the mental health care delivery system has now left children in crisis without access to timely care,” the report said.

Kaylee

Kaylee was 22 years old and living in Florida with her boyfriend when she began experiencing episodes of psychosis, following a traumatic car accident and increased marijuana use.

During those episodes, Kaylee thought people were following her. She thought everything she ate was poisoned. She was worried her boyfriend was going to kill her.

After two hospitalizations, she knew she needed help. She decided to come home to Connecticut to receive better care under her family’s insurance.

She was admitted to the Institute of Living in Hartford for 12 days where she lived with other patients 18 years old and over.

For Kaylee, regulating her medication was critical to her well-being. Diagnosed with bipolar disorder and experiencing periods of psychosis, the right medication was able to help stabilize her. She was given sheets explaining the medication she was on, but said sometimes patients would have to ask for them.

“They cared if you cared,” Kaylee said. “Some people you could tell that they did not want to be there, they did not want to help themselves. But if you wanted to help yourself, the nurses pretty much reciprocated.”

But one nurse stuck in Kaylee’s mind after her stay — her energy seemed to bring the environment down. Residents often complained about that particular nurse, but nothing appeared to come of it.

“You could tell she didn’t want to be there, and that did not feel the best knowing you probably didn’t want to be there either,” Kaylee said. “You’re supposed to make this experience better for me.”

Kaylee was very involved at the Institute, helping organize the main lobby with some activities such as a craft station and talking frequently with other residents about their struggles. In one instance, she even convinced a peer not to sign himself out of the facility and continue his care journey.

“You’re not in the right mindset and you don’t know what’s going on,” she said. “Then you start meeting people that have the same feeling. It’s very comforting.”

Kaylee said the Institute was not always organized — some activities never happened, the calendar was not updated or they did not go outside three times a day as they were supposed to.

People that would have mental breakdowns in there, they kind of just treated them almost like an animal. I really just wish they cared more on a human level than an employee level.

— Kaylee

She recalled one particular resident who would have frequent struggles.

“I know he loved music. If they just played his favorite song, he would literally calm down,” she said. “Don’t just strap him down. That was kind of hard to see.”

Kaylee, now 23, is still on her mental health journey. She is part of a psychosis group and seeing a psychiatrist to continue regulating her medication.

She reminds herself everyday of where she was, and where she could be.

Albert J. Solnit Center

The Albert J. Solnit Center is one of the only state-run psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTF) in Connecticut, operated by the Department of Children and Families (DCF).

Beginning in 2006, when Solnit was then known as Riverview Hospital, multiple problems were found with the facility. Because the program was run by DCF, it was not required to be licensed by the Department of Public Health (DPH), and then-Governor M. Jodi Rell subjected the facility to monitoring of an outside source.

The necessity of Riverview Hospital was re-evaluated in 2011, with legislators and DCF Commissioner Joette Katz proposing a bill to close the facility and explore alternate ways to meet childrens’ needs.

Despite significant problems found with its operation, the bill did not pass.

In 2012, the facility was renamed the Albert J. Solnit Center and the PRTF split into two campuses: North Campus in Windsor and South Campus in Middletown. Solnit North is for boys ages 13-17 and Solnit South spans three PRTF cottages for girls ages 13-17, in addition to the psychiatric hospital for youth under 18 years old. The OCA report from October 2023 showed the wait for Solnit South was around 112 to 140 days between 2022 and 2023.

As of September 2023, the psychiatric hospital had 20 out of 42 beds filled, despite being licensed to accommodate for 50. The PRTF cottages had 12 out of 21 beds in use.

Before licensure, Solnit South was only required by Medicaid law to be subject to outside inspection once every five years, or upon a serious occurrence.

According to records obtained in freedom of information requests, between November 2017 and July 2018, there were seven suicide attempts at the facility. DPH did not conduct site visits until after the third attempt.

When the visit was conducted, DPH found deficiencies in the facility that placed youth residents in “immediate jeopardy of harm.” DPH staff reported that immediate jeopardy findings in PTRFs are rare — so much so, they were only able to provide information for one other occurrence in the five years prior.

There were two immediate jeopardy findings before one resident at Solnit South died by suicide.

On June 28, 2023, 16-year-old resident Destiny G. took her own life the day before she was supposed to be discharged. She was eight months pregnant at the time of her death.

-

Feb. 2018: assessed and admitted

Destiny’s initial assessment at admission reported that with a family history of suicide attempts, she was at a higher risk for this and depression. She expressed wanting a better life for herself and her child through treatment at Solnit. She was admitted on Feb. 6, 2018.

-

April-June: refusing to engage

Two months later, Destiny was starting to refuse engaging with her clinician. April 24 was her last documented individual clinical session. Throughout May and June, her progress notes were less frequent, if entered at all.

-

June 7-15: safety risk

On June 7, a nursing note stated Destiny “presented significant safety risk to herself and staff members.” The following week, she refused to eat.

“I’m tired of people telling me that it will be ok,” she said, according to a nursing note on June 15. “I’m tired of trying.”

-

June 23: five days before death

Five days before her death, Destiny verbally threatened others and expressed she did not care if she was pregnant. Still, she was set to discharge at the end of the week.

The Village for Children and Families was the agency supporting Destiny’s therapeutic foster home. Her referral packet to the agency contained little information on her clinical profile, and any depressive behavior patterns were not communicated.

-

June 27: day before death

Two days before her discharge — the day prior to her death — little details were still known about Destiny’s next placement. Email exchanges between the DCF caseworker and Solnit clinician revealed parts of her case plan unresolved, unmet treatment needs, a history of high risk behaviors and persistent hopelessness. There was no referral for her to continue out-patient therapy after her discharge.

A month later, when the Hartford Courant reported the deficiency findings after Destiny’s death, it was the first time the findings or corrective actions were made public, despite the involvement of DCF, DPH and Department of Social Services (DSS).

Moreover, family members of residents were not informed of the findings. Legislators and the DCF State Advisory Committee were just as unaware.

The OCA investigated Solnit South from January 2017 through June 2018. In addition to the seven suicide attempts and one suicide, they also found over 60 additional “DCF Significant Events,” including absent without official leaves (AWOLs), attempts of self harm, altercations between residents and accidental injuries.

With all of this brought to light, Solnit was required to obtain proper DPH licensure in 2021 and the DPH commissioner had to adopt regulations for licensing these facilities. PRTFs were then defined as “a non hospital facility with a provider agreement with the Department of Social Services to provide inpatient services to Medicaid-eligible individuals under age 21.”

In order to obtain licensure, Solnit North had to hire 10 more nurses and one more psychologist, as well as renovate one of their cottages. Solnit South fulfilled licensing requirements after the DPH investigations in 2018.

The estimated cost to the state for this licensure was projected to be over $1.5 million in fiscal year 2022 and over $1.3 million the following year.

A special act also called for DCF and DPH to create regulations for licensing of PRTFs. The law found there was no licensure category for such institutions, with DCF acknowledging that the child-caring facility regulations did not reflect PRTF care level.

Neither DCF nor Solnit could be reached for comment.

Barrins and Associates was the independent monitoring consultant that helped work with Solnit and DPH to ensure compliance with the state. The current principles of the organization did not share any information on the work Barrins and Associates performed with Solnit, but said they provide general consultation in the behavioral health care industry.

“It varies from organization to organization, depending on what’s needed,” one of the principals, Julia Finken, said. “They contract with us and it could be in response to some compliance issues with the state or with an accreditor.”

The October OCA report also recommended that DCF strengthen its incident and program oversight for timely interventions or modifications to occur, supporting the safety and better outcomes for affected youth.

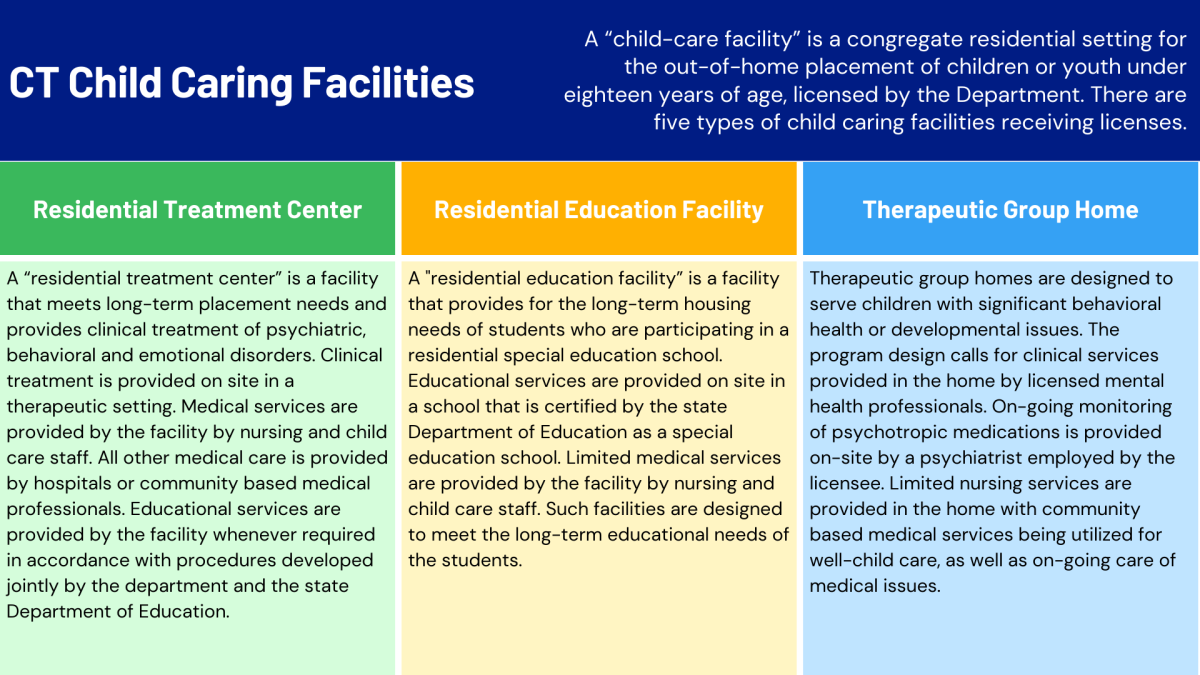

New Jersey’s Children’s System of Care (CSOC) was redesigned in the late 1990s, around the same time as Connecticut restructured its residential care.

PerformCare is now New Jersey’s one-point access center to the CSOC. Parents, caregivers and providers can call for help. They get an assessment and referral to whichever level of care is most appropriate for their youth.

Care Management Organizations (CMOs) are a crucial part of this system as well, with nonprofit organizations that coordinate the services to families through the Child/Family team process and wraparound approach. They provide assessments, comprehensive planning and develop strategies to help sustain the stabilization of youth.

The new care structure in New Jersey also includes Family Support Organizations (FSOs) across the state to serve as peer support resources for families of children with mental health, emotional or behavioral challenges. FSOs connect families to care services in their communities, offer assistance and response to family’s needs and provide necessary resources to keep families together.

Stephanie Marcello oversees the state training contract for the entire CSOC, including the training and certifications, as well as recertifications, for psychiatric screeners. She is also the chief psychologist for Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care (UBHC).

Marcello said the system is mainly viewed as a step-down approach that ultimately depends on what level of care the youth and family may need.

“We’re really focused on the voice of youth, the voice of families,” Marcello said. “It’s not a bunch of people who aren’t working in these services making decisions, it’s really made with the voices of the people that we serve.”

Rutgers UBHC itself has various levels of care: inpatient, psychiatric, outpatient, educational programs, behavioral support and in-home providers or therapy.

The number of New Jersey youth in out of home placements has decreased over the past decade, following other trends seen in the tri-state area.

Youth are assessed for what level of care they may be best suited for with the Child and Adolescent Strengths and Needs Assessment. All CSCO employees operate from this inventory, as the adopted tool works to determine where children need to be placed within the system.

“New Jersey actually has one of, I would say, the strongest systems of care. We tend to be models for other states because of honestly the leadership over at the Division of Children and Families (DCF),” Marcello said.

Marcello said evaluations and assessments of the workforce are constantly done to identify topics that are not being covered. DCF funds about 30 free trainings each month to anyone who works within the CSOC. Different training sessions are offered every month and learning module curriculums are updated annually, changing to include topics such as working with LGBTQ youth, understanding behavior therapy through positive support, creating clinical safety plans and cultural considerations. Coaching is offered for how to implement these best practices.

The CSOC works with the state of New Jersey to obtain federal grants to support this implementation. Much of the CSOC’s latest endeavors include topics of trauma-informed care, creating healing communities for kids and working around trauma and social determinants.

Our mission is always to serve the children and families in New Jersey. And to keep learning, growing and doing a better job at what we’re doing.

— Stephanie Marcello

Marcello said the CSOC has moved away from seclusion and restraint, instead focusing on other techniques such as positive behavior support and positive psychology. New York has adopted the same approach as well.

Specialized certifications are required for many of the roles that exist within the CSOC, with over 10 programs offered through training and coaching. Marcello highlights that the CSOC staff is diverse and often later in their career, meaning they have extensive experience in the specific roles they hold.

Aside from residential care, other services are offered. The Children's Crisis Intervention Services are short-term treatment options for struggling youth, lasting about seven to 10 days for kids who need a higher level of care. There are also Early Intervention Support Services for more intensive support while adolescents transition into other levels of care if they do not have to go to a screening center, or acute psychiatric services.

Marcello said from her interpretation, the CSOC focuses on keeping children with their families whenever possible and providing the family with resources.

“That’s a really strong philosophy of a lot of people working in the state of New Jersey,” Marcello said. “The idea is really that wrap-around — to wrap them in other needed, necessary services to keep the children in the home with the parents.”

Accessibility of care

De Lacy Davis is the executive director of Union County’s FSO, but multiple of his adopted children have received out-of-home psychiatric care.

Davis is a retired police sergeant, author and activist, and found many of the children he adopted, fostered or cared for while on the job. During his time on the force, he said there were far less mental health services in the state than there are today.

He advocates that states should invest in mental health services on the front end and provide children with the treatment and support they need earlier on, otherwise they run a higher risk of being incarcerated or homeless in their adult lives.

But he has seen the effects of investment on the back end as well. Davis has two adopted daughters who spent time in residential care. One of them was in residential placements at different points of her life, and Davis said he can see the attachment issues she experienced from the absence of her mother and father in her life.

For his other daughter, who is diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, residential care gave her life.

“I would be remiss if I didn’t say if it were not for residential and the people there, she would not have gotten to 34,” he said. “That’s the reality.”

But for other youth in underprivileged communities — whether it be in different counties or even states — psychiatric care is not as accessible.

Wilfred Farquharson, IV used to work as a psychologist at Madonna Heights in Dix Hills, N.Y., a residential treatment facility for girls ages 13–17 run by SCO Family of Services.

“Sometimes the hospitalizations will say, ‘Oh look, you’re running out of insurance and you’re relatively stable, we got to get you out of here,’” said Farquharson, who now is the director of Child and Adolescent Outpatient Services at Stony Brook University. “There’s that push to get people back home based off of those factors. We don’t love to talk about it, but it’s true.”

As a parent, I would argue that every residential program is not made equal. It depends on the zip code. It depends on the staff. It depends on the program business model.

— De Lacy Davis

Farquharson also said that zip code matters, with one of the primary reasons being schools.

“The way I used to say it is that the district would pay for the desk and the county would pay for the bed,” Farquharson said. “The school district paid for education programming — also costly but very important — but the county would pay for all the other things in the milieu.”

Because of this, Farquharson describes school-referrals as “direct correlation to zip code.”

“That school district also is going to have more resources, they can send more kids and they can place more kids if they need to,” Farquharson said.

The more youth placed in facilities, the more money it costs the district. And with the school board approving referrals, there is more scrutiny in ensuring the referred students absolutely need the care.

For the mental health care system to be equitable, Farquharson said it would take effort from all sides. Even though there are conversations happening about the issue, the ongoing discussions Farquharson has with his colleagues will not solve the problem — it would have to be a system-level change.

“It would take a lot of empathy from all the people in positions of power,” Farquharson said.

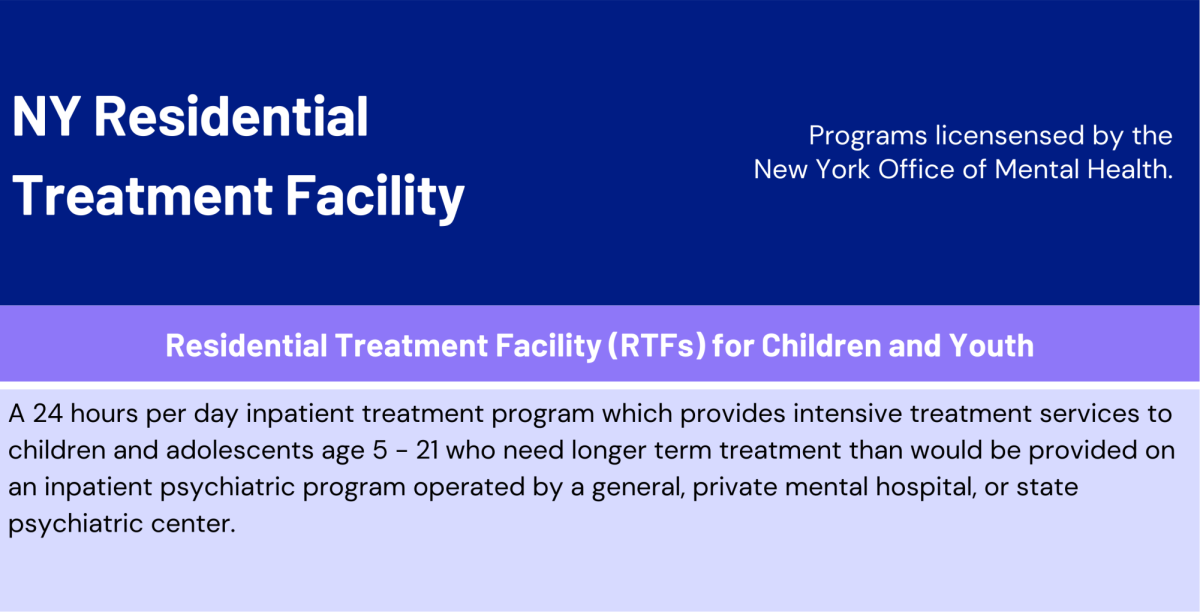

New York has one distinct type of residential treatment program for children and youth: residential treatment facilities (RTFs) provide 24-hour intensive treatment services for adolescents ages 5–21 who need longer term treatment than would be provided on an inpatient psychiatric program operated by a general, private mental hospital or state psychiatric center.

In the past decade, the number of residential treatment facilities (RTF) across New York has fallen. From 2000 to 2014, New York had 19 RTFs. Since then, that number has dropped to 11.

The census of these facilities has decreased as well. From 2010 to 2017, there were about 900 residents each year in adolescent RTFs. That has since decreased to 339, as of September 2023.

This number is still significantly less than New Jersey placements — in 2010, there were over 3,200 youth placed in different intensities of residential care in. As of 2022, there were more than 1,300 New Jersey youth placed, over three times as many as New York.

But that does not mean adolescents or families have stopped trying to receive care in New York RTFs. ProPublica reported that applications have increased since 2018, but approval rates dropped from 70% in 2018 to 50% in 2021. Denials rose from 16% to 29%, nearly doubling.

Even of those admitted, not all actually receive bed placement. In 2020, 444 applications were approved, but only 364 youth were admitted. The New York Office of Mental Health (OMH) could not be reached for comment on this.

Similarly to PerformCare in New Jersey, OMH has a Single Point of Access application for state employees and representatives of providers to make referrals, schedule consults and provide case management services.

In February 2023, Governor Kathy Hochul announced details of a $1 billion overhaul of New York’s mental health care system. New psychiatric emergency programs and behavioral health clinics are set to open across the state for “New Yorkers of all ages and insurance status.”

New legislation will be introduced surrounding school-based services, requiring commercial insurance providers to pay for services that are equal to the upper Medicaid rate. This will ideally “ensure timely access for all children” struggling with their mental health needs.

“It provides us with new policies and programs that will increase access to housing and to outpatient and inpatient services and gives us the tools we need to expand school-based mental health clinics, reduce racial inequities in healthcare and close gaps in insurance coverage for mental health services,” said New York OMH Commissioner Dr. Ann Sullivan in a statement.

The proposed increase includes:

- $20 million for mental health services in schools, with a 25% raise in Medicaid rates for school-based programs. Over $5 million for 137 school-based mental health clinic sites throughout the state, with 82 at high-needs schools where over half of students are deemed from “economically disadvantaged households.”

- $10 million for expanding school-based wraparound services.

- $12 million for expanding home-based crisis intervention and HealthySteps program.

- $10 million for grants to suicide prevention programs for at-risk youth.

- $30 million operating and $18 million capital funds will be dedicated to expanding inpatient beds.

Lauri Cole, executive director at the New York State Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, said insurance reimbursement rates, Medicaid managed care and delayed or denied payments have created a rigid system that is unable to adapt to the changing needs of adolescents.

Advocates with the Campaign for Healthy Minds Healthy Kids said they believe a $195 million investment into behavioral health services could help with some of these issues, as providers could hire over 1,300 clinicians to serve over 26,000 more youth.

Years ago, youth would stay in inpatient hospital care for months before returning home or to step-down outpatient programs.

“Residential treatment is not a hospital. The staffing is less intense, it’s less well trained, doesn’t have the medical supervision,” said Dr. Gabrielle Carlson, founder and former director of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Stony Brook Hospital. “That’s how it can be cheaper.”

Carlson oversaw the division from 1986 to 2013. She began the inpatient psychiatric program there, which ran robustly for many years before policy changes interfered.

When Carlson first started on Long Island, her inpatient unit used to have kids ages 6–12 that stayed about two to three months. During that time, Carlson said medications could be tested to see what was effective and what was not, behavioral programs were in place so youth could learn alternative behaviors and there were skilled staff members to provide care.

When the unit first opened in the 1980s, kids were even allowed to get a pass home overnight to practice the skills they learned, like getting on the school bus in the morning. She said the kids knew what they had to do to get home and wanted to be successful.

“It was successful until it got dismantled because of policy changes,” Carlson said. “The emergency room basically wanted a way to get kids in the hospital and out of the emergency room, and that took precedence over how therapeutic the inpatient unit could be.”

Though she describes the new policies as “well-intentioned,” Carlson said those on the frontlines had a difficult time figuring out the reasons for them.

Another problem is the lack of research to back up the need and effectiveness of inpatient hospital treatment. Carlson has done extensive research herself, but said there is no real way to conduct a study to show the effectiveness of treatment since the hospital loses control once the patient is discharged. Even in programs with multiple step-down programs and services, adolescents can be seen at multiple stages of the process many times.

I don’t know that I can demonstrate to you whether or not those kids would be better off. And because I couldn’t do that, Office of Mental Health said, ‘I’m not going to continue to fund this,’ and the insurance company said, ‘I’m not going to continue to pay for this,’ and so it went.”

— Dr. Gabrielle Carlson

Carlson said the kids that require the most treatment are the ones who pose the greatest risk to themselves and others — they require long periods of time, supervision, well-trained staff who know what they are doing and people who can ensure treatment continues.

She believes another issue is a lack of honest conversation surrounding kids who need the most care: those who are violent against others, habitually are attempting to harm themselves, trying to starve themselves or are experiencing psychosis to the point of doing things over and over not because they are angry, but because voices are telling them to.

“To some extent, we are our worst enemy here by not being candid about what it is that we’re trying to take care of,” Carlson said. “We know what they need, we don’t know how to fix what they’ve got.”

Another common issue is the lack of supervision at facilities. At the Timothy Hill Children’s Ranch in Riverhead, N.Y., a concerning number of residents were running away from the facility, even after a 16-year-old who escaped was found murdered in a Centereach backyard. There was video evidence found of youth outside the facility in the middle of the night, unsupervised, running in the snow with no shirt, shoes or even socks. There were also videos of youth choking and slapping each other in their sleep as part of internet ‘challenges.’

Instances of lack of supervision are not uncommon. Amari, an 11-year-old from Rochester, was also unsupervised outside the facility she was placed in until the morning. The investigation into Solnit South in Connecticut found multiple AWOLs went completely unreported.

“The ambiance that you have in a place where [the kids] know you can’t take care of them is much scarier and much less therapeutic than an environment where the kid feels, ‘Okay, they do know what they’re doing. I can trust them,’” Carlson said.

Carlson places an emphasis on the importance of relationships in these therapeutic settings. Positive relationships can have a significant impact on patients, which are harder to form when spending a short amount of time in various facilities.

And with a cost for some facilities like Solnit South of $2,000 per bed, per day — totaling over $1 million a year — it can be expensive to keep youth there long-term.

“You’re supposed to care about the kids,” Carlson said. “But then people aren’t necessarily willing to put their money where their mouth is.”