Congratulations, Long Island. You win the prize for creating the perfect habitat for sharks to thrive in – not the ones made infamous by Stephen Spielberg’s movie Jaws – but for smaller ones.

After Spielberg introduced Bruce, the great white in his 1975 film, getting attacked and killed by a shark while swimming in the ocean very much became a simultaneously real and unrealistic concern for the summer ocean beachgoers – even here on Long Island’s beaches.

But this was just the first in a long line of shark-scare movies in Hollywood that detrimentally changed public perception of these 16 foot-long fish. Suddenly, sharks were no longer viewed as part of the marine ecosystem, or as the cunning apex predators that they are, but as giant underwater mass murderers whose only goal is to hunt down humans.

A major problem arises when this fear becomes so great that the species suffers from a lack of public awareness and care about their importance in our ecosystem. It’s a struggle mostly derived from these films–even though it’s been nearly 50 years since the movie was released– because we still fear sharks as if we are perpetually living in a Jaws nightmare.

On Long Island, sharks have brutally suffered from overfishing, and in some cases have even become endangered–something that’s not unique just to our waters.

More than anything else, this is why shark science and shark conservation remains an integral part of marine studies, despite popular public opinion. It comes down to one factor alone: without sharks, the ecosystem is in grave danger and without conservation to protect them, sharks are at a loss.

History

What many people don’t know about Long Island is that being a home to sharks is a “prize” long-held on the island. Sharks are nothing new to the marine ecosystems off the coast. Although Long Island has seen more action and interactions between people and sharks in recent years, particularly in the summer of 2022 when there were 6 shark attacks on the south shore, Long Island has been a home to sharks since the 1800s. That’s only just how long their existence has been documented on Long Island; there’s every possibility that they’ve been here for significantly longer than the time spanning the early 19th century.

Chris Paparo is the Marine Sciences Manager at Stony Brook University’s School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences, or SOMAS, in Southampton, NY. As someone who has been studying sharks for more than 20 years, Paparo said that sharks are actually nothing new to the Long Island ecosystem.

“There’s actually been speculation going back as far as 1800 on that idea that these sharks might use this [Long Island],” he said.

Despite what seems like a new appearance of sharks on Long Island, SOMAS Ph.D. student, Brittney Scannell, said the same: that for hundreds of years, Long Island has been a home to sharks.

“Sharks have been coming to Long Island for a really really long time,” she said.

Though this is true, there was still a time when sharks were driven away from the island by human actions and human interactions with the environment.

“But then we–as, you know, just the human species–we grow; we polluted the waters and we drove out all the food,” she added. “And we overfish them.”

According to the 2022 Impact Report from the Shark Conservation Fund, the loss of sharks to the marine ecosystem is absolutely detrimental, and affects more than just the other marine life in the ocean. Yes, humans too are affected by the loss of sharks.

It is crucial that sharks remain a living part of the marine ecosystem.

“We just don’t know enough about them,” Paparo said. “And being an apex predator, they’re extremely important in the bigger picture. Without sharks, we don’t have all the other fish.”

So Why Long Island?

Long Island itself is a unique location for shark populations to gather because it forms the northern border of a theoretical body of water; one that is not actually new, but simply refers to the Atlantic Ocean. This triangular body of water is called the “New York Bight, which is an area from Montauk to Cape May, New Jersey,” Paparo said. The New York Bight includes the south shore of Long Island and the east coast of New Jersey, both of which border the North Atlantic Ocean. In New Jersey, it also cuts into part of the Delaware Bay, off of the southwestern coast of Cape May.

This is one of the reasons why Long Island is such a hotspot for sharks. Its place in the New York Bight makes it a distinctive habitat for sharks– so much so that the populations that move through the New York Bight are often studied by scientists to gather multitudes of information about habits of the species.

“We want to know how are they using it,” Paparo said. “Are they using it as a nursery ground? Or, mating/breeding ground? Are they using it just as a pass-through– like they’re only here certain times a year? What temperatures do they like?”

These are just some of the questions that scientists are trying to answer through shark research off of Long Island.

So why does the New York Bight make Long Island particularly habitable for sharks? Well, the answer lies in the marine ecosystem found off the southern coast of the island.

Similar to the way in which sharks are populating the New York Bight, their food source is also swarming the area in droves. Bunker, more commonly known as Menhaden, are medium-sized silvery fish that inhabit the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Long Island. Though they can grow to be only 15 inches long, according to the NOAA Fisheries Species Directory, they taste quite delicious to a predator species like sharks and they attract sharks to congregate in certain areas.

“The main reason that there are more sharks in Long Island waters these last few years, is primarily because there’s more of their food,” Greg Metzger said. “That food is the Menhaden, or the Bunker.”

Metzger not only works on shark science research with Paparo, but he also is the volunteer Field Coordinator for the South Fork Natural History Museum’s shark program. The museum’s shark program is significant, as it heavily contributes to progression in shark conservation and shark research in national marine studies.

“That’s the primary driver for all of the sharks that we’ve been seeing,” Metzger said. “There’s more Bunker in our waters, and the predators follow the prey.”

Bunker, in particular, is one of the most significant factors that plays a role in bringing sharks to our shores.

“Actually, Bunker is probably the most important fish in our waters,” Paparo said. “Even though you can’t eat it, it’s still one of the most important because everything else does.”

The New York Bight provides a plentiful amount of food for apex predators like the sharks. The particular geographical situation of the New York Bight means that it sits right in the middle of two coast lines– where food for predators at the top of the food chain is found most readily.

“There’s an abundance of food,” Paparo said. “The New York Bight, it’s close to shore, you have a lot of nutrients.”

Aside from the prosperity of the New York Bight as a whole in terms of being a good food source, just Long Island waters alone provide an immense amount of food for these local sharks.

“Fish is what they’re primarily eating: Bunker, Mackerel, different types of schooling fish,” Paparo said. “That’s all stuff that’s very abundant in our waters.”

But the food source here isn’t the only reason why Long Island is the perfect home for sharks. Many of them also use the New York Bight as a nursery for their young.

“It’s one of the busiest metropolitans in the world, you know, New York harbor is in the center of it,” Paparo said. “But with some of the research we’ve been doing, we found that that area is an important nursery ground for young-of-the-year white sharks– the great white.”

“Young-of-the-year” is a marine-specific term for the ways in which fish are categorized by age; it refers particularly to “all of the fish of a species younger than one year of age,” as defined by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. For baby sharks, a nursery is the perfect place to live because they are ‘enclosed’ in a metaphorical safety net in the New York Bight.

“They’re in a habitat where it’s protected, and [with] a lot of food, so it’s a nursery for them,” Paparo explained. “It’s a place where they’re ‘safe’.”

Paparo himself, along with a team of researchers, was actually the one to confirm that the New York Bight was a breeding ground.

“The data came back that, yeah, they’re using the coastline of Montauk to Cape May,” he said. “It changes with the season, they’ll go a little further east later in the summer.”

But it wasn’t just a shocking or fascinating local discovery. It was an extremely significant one in the field of shark science.

“That’s one of the only nurseries–one of few nurseries–known of the White Shark in the world,” Paparo said. “That was a pretty special find.”

Types of Long Island Sharks

The sharks that are on Long Island are not the kinds that are portrayed in movies as mindless killing machines. Luckily, Long Island isn’t a permanent home to adult great whites–even if they have been spotted occasionally off of the coast–particularly because of the lack of their favorite meal: seals.

“Especially in the summer months, we don’t have a large population of seals,” Paparo said. “They’re here in the wintertime, and there have been sightings of adult White sharks off our coast in the wintertime.”

However, despite the lack of adult great whites year-round, there are several other species of sharks that consistently inhabit Long Island waters, and have been doing so for years. That’s not to say that there aren’t any great white sharks on Long Island either. The difference is in their age. Long Island is typically home to Young-of-the-Year great white sharks, which inhabit the nurseries.

“I believe the number is about 26 different species of sharks, skates, and rays that are in New York waters throughout the course of the year,” Metzger said. “The list of sharks that we catch typically include Sand tiger sharks, Sandbar sharks, Dusky sharks, young-of-the-year white sharks, Common thresher shark[s], Spinner sharks.”

The list doesn’t even stop there. There are countless different kinds of sharks in Long Island waters, totalling “about a dozen different species of coastal sharks,” Metzger said.

“Smooth hammerhead sharks are another one, the Shortfin mako,…the Blue shark, are ones that we will typically encounter when we’re out during our field season,” he said.

It’s important to note too that the field season for Long Island shark researchers like Metzger runs mostly in the summertime. This is a direct response to the kinds of sharks that they are looking for, which follow specific migratory patterns.

“Typically the sharks that we target arrive in our waters around mid-May, and are here through the end of October,” he said. “It’s basically temperature that primarily drives their arrival and departure.”

So the ultimate question to be asked is why are sharks so important to our marine ecosystem? Why does it matter that Hollywood made people so afraid of sharks? It comes down to one simple answer: they are what helps the marine ecosystem function properly. Without sharks, should they ever be overfished to extinction, the entire marine ecosystem collapses.

Lucas Iudica, an undergraduate research tech in SOMAS’s Peterson Lab, discussed what he has learned as a student working in this area with the shark scientists.

“These upper echelons of the trophic system, or the food web, have a very strong impact on everything below them,” he said. “But sharks as, you know, major predators in the systems, are a very good indicator of the system’s health.”

There’s a very clear correlation between the success or health of the shark populations and that of the rest of the marine ecosystem.

Sharks themselves become an indicator for scientists about the state of the local marine ecosystem and can often inform them as to the problems going on within.

“Having those top predators, they keep things within check,” Paparo said. “They get rid of the sick, and injured…they’re going to take out the weak, keeping the other population strong.”

For Long Island, then, it’s a good sign that sharks are populating the waters off of the southern coast so abundantly, contrary to what many people might initially assume.

“Long Island in general is rich in marine life,” Paparo said. “We have all sorts of sharks, we have all sorts of fish, [in] wintertime we have all sorts of marine birds that come down from the high tundra to spend their winters here.”

The number of sharks living in the New York Bight–as well as the number of sharks returning each year during their migration–means that Long Island’s ecosystem is thriving.

“These signs are actually really good signs for the ecosystem that we’re seeing more sharks,” Scannell said. “It means that the ecosystem is functioning better than it was in the past decade.”

This just adds to the long list of reasons why Long Island is a prime location for sharks. Essentially, Long Island is simply unique in its quality of life for sharks and all kinds of marine life.

“We have a really awesome environment around us,” Paparo added. “I think people just don’t appreciate what’s in our backyard.”

Sharks play a massive role in keeping our environment as “awesome” as it is. Without sharks, it’s clear that the other marine populations below them in the food chain would erupt into utter chaos.

Local conservationist and ecologist Carl Safina emphasized this importance of sharks to the ecosystem–not just on Long Island.

“Sharks do eat other things,” Safina said. “First of all, the things they eat would probably become more abundant…so in that case, if the things they eat become more abundant, then the other things that those things eat would get less abundant because of what is called a trophic cascade.”

Cascade is a fitting term for the image that is conjured up by that scenario. It’s easy to imagine how a loss of sharks in their entirety could cause a mass ripple effect through the marine ecosystem and a cascade of destruction along with it. Of course, Safina didn’t discount the fact that these imaginary scenarios or predictions based on prior facts are all that can come out of asking questions like, what happens if sharks go extinct?

“It’s not clear what would happen because things are very complex,” he said. “Nobody exactly knows.”

However, one thing to mention is that there is a possibility that each species of shark could cause a different impact in their ecosystem if they were to go extinct.

“I would say with confidence that it would vary from shark to shark and from ecosystem to ecosystem,” Safina said. “It’s probably a different thing on the east coast here than it would be on a coral reef in the South Pacific.”

Still, there is no doubt that sharks themselves are crucial to the marine ecosystem and uphold the structure and function of it in everyday life.

“Use of these marine predators as indicators of system health has sort of been a very important topic over the last you know, 10, 15 years,” Iudica said.

Scannell most strongly emphasized that sharks in the ecosystem are just, “important apex predators.”

Climate Change

When talking about sharks in the marine ecosystem, the conversation about climate change can’t go untouched. Since a part of climate change involves warming waters, the effect that these changes have on marine life, like sharks, is undoubtedly in question.

“Often people are blaming climate change…climate change is a hot topic and it’s happening and we’re seeing results of climate change,” Paparo said. “Climate change is going to have an effect on all marine life.”

However, it’s generally understood across the board that shark population numbers are not directly affected by climate change.

“As of right now, the science isn’t there to support any sort of statements about climate change and their impacts on sharks or their populations,” Metzger said.

The frequent appearance of sharks on Long Island is not a direct reflection of climate change either. It comes down to the species of sharks on Long Island that have actually been altered from climate change.

“With the sharks, climate change necessarily isn’t going to make us have more sharks here, ” Paparo added. “It’s going to change the diversity of sharks that are here.”

The variety of sharks on Long Island has expanded as climate change has worsened across the globe. Again, with warmer temperatures come tropical marine life that are more conditioned to that warmer water. Similarly, in reverse, the marine life that’s more suited to colder water moves further away from the incoming warm temperatures.

“As water temperatures rise, our typical local species–makos, blue sharks, white sharks–they like cooler water,” Paparo explained. “If the water starts to get too warm, they’re going to shift north. The species that are further south, it’s going to get too warm for them [so] they’re going to shift north.”

That is the number one visible impact that can be seen from climate change on shark populations. Their migration patterns are changing, extending further and further north.

“What you’re going to see first is things moving north,” Paparo said. “Eventually the ones that migrate are still going to run out of room. There’s only so far you can go before it starts getting too warm there too.”

Climate change more generally affects oceans and marine life as a whole, as it isn’t so clear how it affects one particular species.

“Global climate change as a whole is changing so many systems that are so wildly interconnected, that it’s very, very difficult to pick out, okay, this one factor is affecting this one species,” Iudica said. “It’s very inconclusive.”

This process of seasonally targeting sharks off of Long Island’s coast isn’t just a fun past-time or hobby for these researchers. It serves an incredible purpose and an extremely important role in shark science as a whole. The scope of knowledge about sharks is limited, and part of the effort in conservation and research is to tag the sharks that are found in Long Island waters.

“There’s a tremendous amount of information that we don’t know about sharks,” Metzger said. “The original tags were basically non-electronic, plastic tags that would be inserted into the shark, and it would give you a sense of where the shark was in place and time.”

Tagging sharks off of Long Island, and in other parts of the world, can help scientists to understand more about what the day-to-day life of a shark looks like. While tagging has been a practice long instated in shark science, technological innovations have undoubtedly aided in the ease of this process.

“Thankfully technology’s advancing in all areas including tags,” Metzger said. “We have satellite tags which will go onto the shark…that follows the shark, stays on the shark, and records the temperature of the water [and] the depth of the water every 10 seconds for 28 days. It then releases from the shark and can relay that information via satellite to our computers.”

Since technology has advanced so dramatically from those early days of shark-tagging, it’s become significantly more efficient to collect the data from these sharks.

“We don’t have to get the tags back to get a tremendous amount of data from that shark,” he added. “It’s become very sophisticated.”

Tagging in particular is so important to shark science because in general, it can be very unclear why sharks populate certain areas at certain times. Tagging at least provides some insight into the different possible answers.

“There’s many reasons why we could have sharks here,” Paparo said. “There are many reasons, nobody knows for sure. There are hypotheses on what’s causing it and there’s new research going out to confirm these.”

Like Paparo spoke about, some of these hypotheses pose possible answers for why sharks are inhabiting Long Island waters, such as the immense improvement in conservation efforts to protect the local sharks and, mainly, an abundance and resurgence of their food source.

But additionally, a massive part of the conservation efforts put in place to protect sharks concerns one of their most harmful threats: overfishing. Without any kind of regulations on licenses for fishing, sharks are vulnerable to being caught and killed, which overtime can slowly depleting the population.

However, the United States is one place where that isn’t necessarily the case anymore, now that there have been certain governmental regulations put in place on different species of sharks to protect them from becoming endangered. Shark populations in the U.S. in particular are protected by the government and our fisheries are monitored closely.

“It’s managed properly and there are regulations in place,” Paparo said. “But [in] other parts of the world, that’s not always the case.”

This protection goes so far that there are even some instances in which fishermen can’t catch a certain species because they are so vulnerable and need to be left completely untouched in order to remain alive.

“Locally, makos are a completely prohibited species,” Paparo added. “Even on our permits, we’re not allowed to retain them…we’d have to get special permitting for that– they’re that protected.”

Mako sharks are the prime example of how U.S. regulations on fishing have helped in conserving the species. Before the regulations were put in place, the species was in dire straits.

“So makos…are really big sport fishing sharks that people are looking to–and you can actually take, and people eat–but makos declined super, super heavily,” Scannell said. “It is really interesting to see actual regulations start to go into place; and you couldn’t fish for mako this summer, which was really cool.”

The regulations have proven effective too, as species that were previously vulnerable and depleted have regained a larger population standing in the United States.

“There’s several species of sharks that have shown increased populations, based on all of the available data since the early ‘90s, which is when a major shark regulation was put in place by the federal government,” Metzger said. “So there are more sharks in our waters because of positive conservation efforts…30 years later, we’re starting to finally see some increase in shark populations.”

Yet, the thing to understand still about conservation is that although there have been changes and improvements made to shark populations, “it’s far from recovered,” as Metzger said.

These governmental regulations are controlled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, which plays the most important role in this entire process by setting up rules and regulations that U.S. fishermen have to abide by.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Conservation plays a huge role in increasing the number of shark populations both locally and globally. Conservation efforts have not only been implemented on Long Island, but also at a national level. NOAA is the government organization responsible for putting marine conservation practices in place on a national scale for all different kinds of marine species under many different divisions and departments within NOAA.

Tobey Curtis, the Fishery Management Specialist in NOAA’s Atlantic Highly Migratory Species Management Division, said in an email interview that the Highly Migratory Species (HMS) Management Division particularly focuses on “conservation and fisheries management of over 50 species of sharks, tunas, and billfish in U.S. Atlantic waters, from Maine to Texas and the U.S. Caribbean.”

Sharks themselves are considered a highly migratory species, as they tend to travel based on water temperature, in which “their migrations generally track that preferred temperature ‘envelope’,” Curtis said.

“It’s not about finding warmer or colder water, it’s about always staying within that comfortable temperature zone,” he explained.

Even the NOAA participates in similar conservation efforts to what scientists and researchers are doing on Long Island for local sharks. A huge part of the NOAA’s role in shark conservation comes down to numbers, once again.

“NOAA and academic scientists collect data on numerous shark populations up and down the coast,” Curtis wrote. “We conduct longline surveys, collect biological samples, compile data from fishermen, conduct tagging studies, and other efforts that support population assessments.”

The big impact of the NOAA compared to local conservation organizations is that it is a government organization, therefore, it can work closely with and petition to alter U.S. conservation law. This makes a massive difference in national shark conservation.

“The HMS Management Division helps convert that science into sustainable fisheries management regulations consistent with U.S. law,” Curtis explained.

When talking about conservation, the question that always comes to mind is: do we need conservation because the species is considered endangered? So then, are sharks endangered? Well, there’s actually no definite answer to that question. Sharks are too numerous with too many species varieties to determine in a black-and-white manner whether they are endangered or not. Each species is very different and should be treated as such, Curtis said.

“It is important not to lump all ‘sharks’ into one basket when you’re talking about conservation, biology, or beach safety,” he commented. “Some species are overfished while others are not. Some species are more dangerous to swimmers than others.”

The fisheries management work that the NOAA does and the conservation laws, such as the Endangered Species Act, help to significantly improve the number of sharks nationally. While Curtis mentioned that different shark species are “threatened or endangered with extinction,” while other shark species are not, there is no denying that on a global scale, “about one third of sharks and rays are considered threatened,” he said referring to data taken from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Distinctly, it is clear that efforts put in place by the U.S. government to protect our waters and our marine life have been effective. Due to the fact that the government implemented the Endangered Species Act, sharks have been saved from extinction, at least in the north-Atlantic region.

“There are no sharks from the northeastern U.S. that are ‘endangered’ under the Endangered Species Act,” Curtis wrote. “This is mainly because responsible fisheries management that began in the 1990s has prevented species from becoming endangered.”

Again, there is a distinction to be made between going extinct and becoming severely depleted as a population. For the most part, sharks take up the role of the latter, as overfishing was one of the main problems for any kind of dip in shark populations.

“Many shark populations are recovering from overfishing that occurred in the 1970s-1990s, but they are not endangered,” Curtis said.

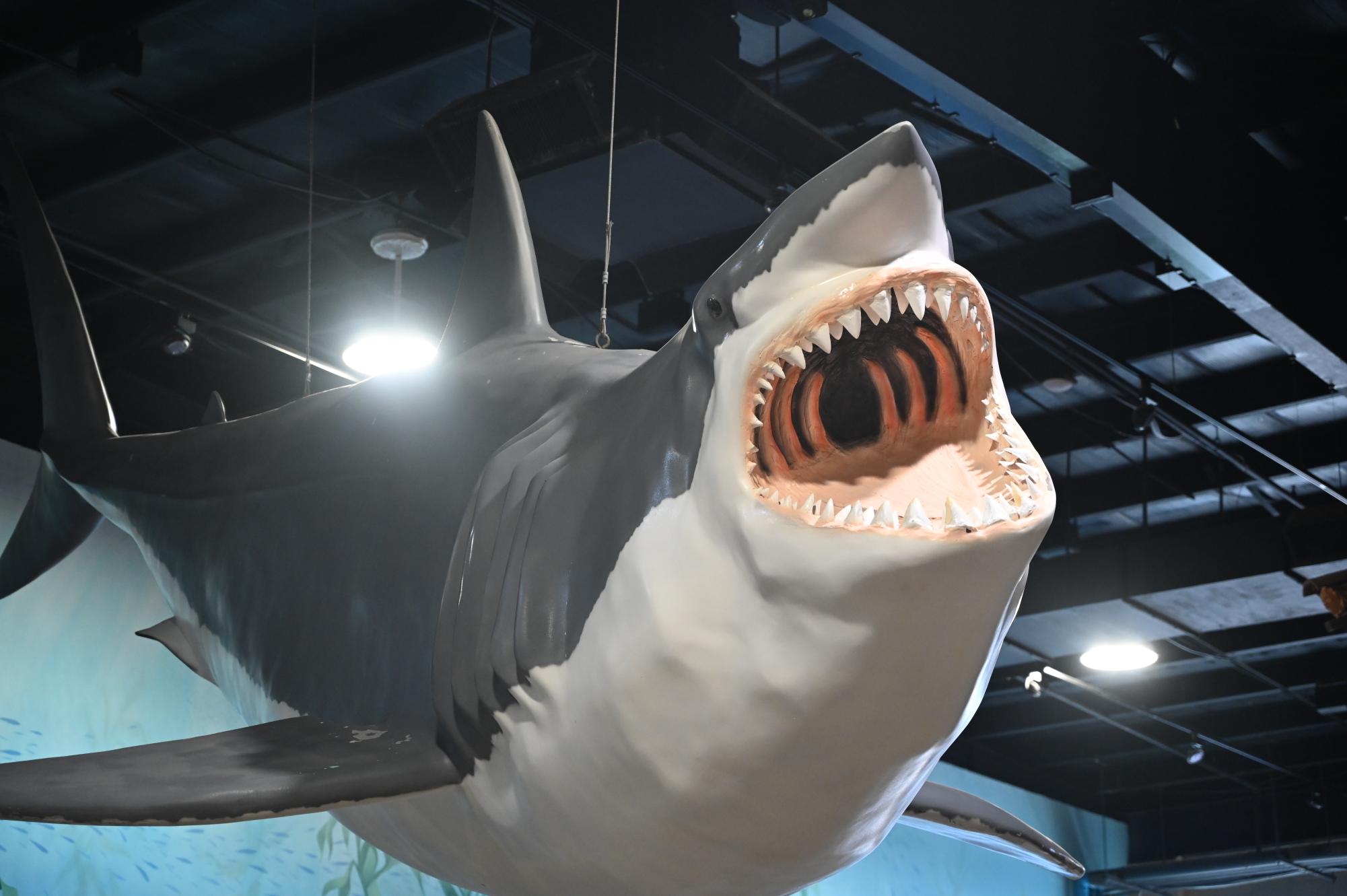

The Long Island Aquarium

To locals, the Long Island Aquarium is known as the hot-spot for shark sightings– that is, of course, behind thick panes of glass. Their large shark exhibit, themed as the Lost City Shark Exhibit after the mythological story of the lost city of Atlantis, contains two species of sharks and serves as a learning opportunity for the public in understanding the sharks in the waters of Long Island.

Ted Tilkin, an assistant curator at the Long Island Aquarium who heads up the fish department, spoke about the extent of the shark exhibit at the aquarium.

“I do take care of the shark tank,” he said. “The 120,000 gallon Lost City of Atlantis shark habitat, home to four Sand tiger sharks, four Nurse sharks and a bunch of other fish that you could find throughout the area.”

While the Long Island Aquarium may not approach conservation in the same manner as Stony Brook’s SOMAS or the NOAA organization, keeping these sharks in captivity serves its own measure of conservation. The aquarium understands the significance of sharks to the marine ecosystem and informs the public about their necessity.

“Sharks are really unique animals,” Tilkin said. “They are a keystone species, they are the reason the oceans are healthy to this day. They play such a vital role in the entire ecosystem.”

Part of the aquarium’s efforts in shark science and conservation is keeping these eight sharks in captivity where they can monitor, take care of, and protect them.

“A lot of animals generally benefit from aquariums and captive environments due to a bunch of factors that kind of play into their everyday lives,” Tilkin said. “They’re getting three meals a week…they get vitamins, if they have certain ailments they’ll get medications and things like that.”

The aquarium’s efforts in shark conservation are also apparent in the lives of the sharks themselves. In a way, the species is protected by the aquarium because they have a higher chance of living for a longer time than they would in the wild.

“As certain animals get older, they start to get weaker and then maybe they either get sick or something happens to them,” Tilkin said. “Because we’re able to prevent a lot of that, we can sometimes see increased lifespans.”