Fifteen years ago, Shannon Carpenter found himself throwing up in a urinal at his office. He had just told his boss that he was quitting the position he had held for eight years as an elder abuse investigator. He was becoming unemployed for the first time in his life.

It was a carefully-made decision. His wife was pregnant with their second child and they both realized that he was spending more time at work than with his family. At the time, he left his daughter at daycare at 7 a.m. and only saw her again at 6 p.m. Because of the unpredictability of his job, it wasn’t uncommon for him to leave the house in the middle of night to “fix something.” He had a college degree and a full-time job, but was basically working to pay for his daughter’s daycare. And although he was working on something he believed in, he was unhappy.

One night, he and his wife had a conversation. One of them would have to stay at home to take care of the kids, and he joked that it should be him. He laughed, in fact. But then, it dawned on him: it had to be him. He wanted to do it. He thought he would be better at it. His wife had recently been headhunted, which significantly increased her salary, so, financially, it made more sense if he was the one who would stay with the daughter. There was no way back.

After months of planning, he told his boss that he was leaving. As he walked back to his office, he panicked. He ran to the bathroom and splashed water in his face. Suddenly, the dry heaves became unmanageable. He went to the urinal where a hot wave gulped out of his mouth and kept going for three minutes. He had officially become a stay-at-home dad.

Carpenter Zooms in from a room of purple walls just outside Kansas City, Missouri. He rests his strong arms on the table and stares at the camera seriously, focused. It’s not the best frame. The top of his head is cut off the screen and a stream of light coming from above blurs the image. However, it’s still possible to see his face. He looks like Helsinki, the character from the Spanish miniseries Money Heist: burly, with a long gray beard.

He puts on a smile as he speaks, breaking the deceptive seriousness of his gaze. His voice is firm, confident. His constant use of words like “man” and “dude” help break from that first impression and hint an easygoing personality. The more he dives into his relationship with his children and his ideas of what it is to be a good man, the more he becomes Helsinki in my head: unbreakable and cold, but sensitive and full of heart.

At 48, Carpenter has three children: 17, 15 and 10 years old, and has devoted his life to raising them. In the beginning though, it was hard to accept that staying at home to raise children was his new reality.

The idea of work as a key aspect in the perception of manhood isn’t new. Joseph Vandello, a social psychologist who studies gender issues with a focus on manhood at the University of South Florida, published a study in 2014 which pointed out that men more than women saw unemployment as a potential cause for gender status loss.

“It wasn’t the case that women thought other people would see them as less womanly, but it was the case that unemployed men thought others would see them as less manly,” Vandello says.

Aiming to understand how unemployment influences a person’s perception of who they are and of how others perceive them, Vandello and his colleagues surveyed a nationally representative sample of adult men and women who were involuntarily unemployed during the 2008/2009 recession. The results indicated that men’s understanding of unemployment as an identity threat was associated with distress and anxiety.

“I think that all speaks to the issue of the importance of work to manhood,” Vandello says. “What happens when that [part of their identity] goes away?”

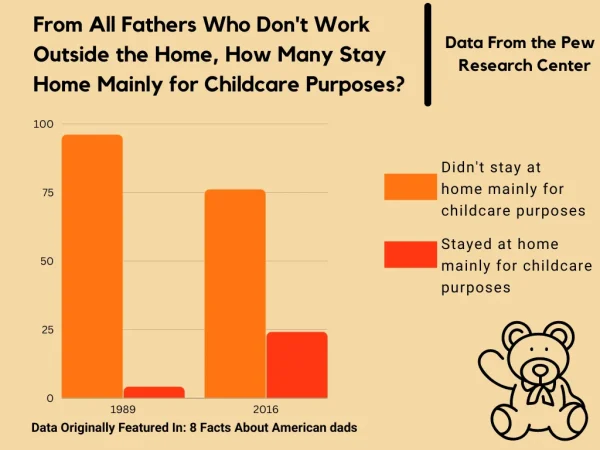

This is a question that likely haunts millions of men in the United States. The Pew Research Center reported that 2 million fathers didn’t work outside of their home in 2012. Although 23% of them said that they were staying at home because they couldn’t find a job, 21% said that they stayed at home to take care of their home and family, which represented an increase from the 5% who said so in 1989.

This growth pattern has continued over the years. Pew Research found that the total percentage of U.S. fathers who stayed home to specifically take care of their children rose from 4% in 1989 to 24% in 2016.

Catherine Marrone, advanced senior lecturer at the Department of Sociology at Stony Brook University, says that this increase might have to do with two factors. The first is that the perceptions of gender roles are becoming more flexible, which makes it more comfortable for men to make childcare their primary role. The second is that there are more women in the workforce potentially outearning their children’s fathers — who may or may not be their husbands.

In 2013, a Pew Research Center analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau data showed that mothers were either the primary or the sole financial provider in 40% of households with children under the age of 18. Regarding married women specifically, another report published this year by Pew Research documented that 16% of marriages in the U.S. have a primary or sole breadwinning wife. In 1972, this was the case for only 5% of marriages.

Historically, the second wave of feminism, during the 1960s and the 1970s, marked the period when women started to argue for control of their lives by, for example, having the ability to get credentials and the ability of having reproductive control.

“You also start to get changes in the number of women who are going into the workplace, and the number of women who are going to college and the number of women graduating from college,” Marrone explains.

That second wave of feminism was a movement led mostly by middle and upper middle class women, which didn’t bring much change for women and communities of color, Marrone explains. The third wave of feminism, however, is characterized by a push for more people of color in positions of power and by a bigger understanding of gender identities.

More women are assuming positions of power in the workplace, but parity still lacks, Marrone notes.

“There is still a wage gap between the earnings of men and the earnings of women,” she says.

Another study published by Pew Research in 2019 clarifies that women might be spending more time in the workplace, but they are also spending more time on childcare. Overall, mothers still spend more time than fathers on caregiving. Also according to the study, women are becoming mothers later in life.

“They’re not necessarily able to have kids at a younger age, they’re putting off their fertility, so they’re having fewer kids, and they’re having them later,” she explains.

Still, many of the fathers who are now staying home struggle to find support in their communities, Marrone says. Differently from a neighborhood in the 1950’s when all the women stayed at home and connected with each other, men who stay at home today don’t usually have peers, or the ability to connect to other men who also stay at home.

“They are kind of left out and feeling isolated,” Marrone says.

Carpenter experienced this isolation first hand. When he started as a stay-at-home dad, there were no dads groups he could contact, he says. Moreover, he wasn’t confident introducing himself as a stay-at-home dad.

“As men, that’s how we identify ourselves until we introduce ourselves,” he explains. “‘Hey, my name is Shannon, you know, what do you do for a living?’”

For him, it was almost weird that both his grandfather and his father were delighted when he told them that he was becoming a stay-at-home dad. Carpenter belongs to a family of veterans. His grandfather is a World War II Navy veteran, who, after the war, pursued a career as an engineer. His father was disabled in the Vietnam War, and became an accountant after he came back to the U.S. Carpenter describes them as the two of the most manly men he met in his life. They both had a tremendous impact on his life and they were truly his heroes.

“They told me I would never regret a single day I spent with my kids, because that’s what they missed,” he says.

From a broader perspective, Carpenter has a reason to be surprised that his grandfather and father were happy with his decision. Vandello’s research points out that men tend to seek work-life balance less than women when looking for a job because they are afraid of being stigmatized for doing so.

In 2013, Vandello conducted a study to understand the social and psychological penalties that a person experiences when deviating from the social norm of complete devotion to work, which he named “work flexibility stigma.” Vandello asked college seniors what they prioritized in a career and how much they would pursue what they wanted professionally. The study found out that having a good salary was unquestionably the main priority and, most importantly, that, although work-life balance was a priority for both genders, women were much more likely than men to actively explore career paths that led to a good work-life balance.

The gender difference in this situation is anchored not in the desire to live a well-balanced life, but in the fear that men experience when deciding whether or not to pursue this balance.

“They don’t think that they can do it,” Vandello says.

In a follow up study, Vandello created hypothetical scenarios to understand how people see workers who seek a flexible work schedule. One of these scenarios hypothesized that a person just had a baby and decided to move to a part-time position to dedicate more time to childcare responsibilities, a situation very similar to the one Carpenter found himself in 15 years ago. Vandello’s study found out that, as much as both genders were financially penalized, men were also gendered penalized as people concluded that they were less manly for wanting to work less.

“There’s a kind of an extra penalty for men,” Vandello explains.

A couple years ago, Carpenter recalls, he went to the doctor’s office and his doctor was devastated to find out he was a stay-at-home dad, as if that was an accident rather than a choice. He explains that the changing point to deal with this judgment was understanding that he could do anything in life. At the same time that he has done traditionally masculine things like rebuilding decks and remodeling bathrooms, he has also allowed himself to explore other activities such as baking tarts and cookies.

Although unsettling in the beginning, today Carpenter speaks about being a stay-at-home dad with pride, convinced that his value as a man is not tied to his job. He highlights that a paycheck isn’t what makes a man a man and that, just because other men make more money than him, that doesn’t mean they are any better.

“Is Andrew Tate a better man than me? Absolutely not,” he says.

Andrew Tate, a 36-year-old former professional kickboxer, gained media attention after he started making digital content promoting the idea that men need to “escape the matrix” by becoming what he calls alpha males. Tate was accused of racism and misogyny multiple times. His hate speech violates community guidelines of most social media apps, which led to his ban from Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter and Twitch last August. In December 2022, he was arrested in Romania, accused of rape and human trafficking.

Yet, after Tate’s arrest, his videos can still be easily found on the Internet and his success sparked the emergence of multiple influencers that share similar thoughts to him.

Twenty-three-year-old Ares Delara introduces himself as a professional men’s dating coach. He has over 100,000 followers on his TikTok account. Delara says that he has been watching Tate’s content since before Tate became famous and that, although he doesn’t agree with everything that Tate says, he likes Tate’s lack of fear of being canceled.

“One of the reasons why I really liked [him] is because of how he was able to express himself and not care about backlash or about what other people thought,” Delara says.

In his opinion, men in today’s western culture lack masculinity, which forces women to become more masculine. For him, that’s unfortunate.

“It’s not a woman’s natural role to be the man essentially,” he says.

On the topic of stay-at-home dads, Delara believes that a man who stays at home to take care of the children must be more feminine, and that can’t be good for him.

“Men need some type of purpose, they need challenge, they need things that they are achieving,” he argues. “Especially for a guy in his 20s or 30s, I don’t see that as something that is good.”

However, Glen Henry, who was a stay-at-home dad during three years of his 30s, saw that as an opportunity to step into someone else’s shoes and see the world from a different perspective. He remembers that while his friends complained about returning from work and not finding a clean house and a cooked dinner, Henry would tell them to “cut their wives some slack.”

“You really don’t understand what your wife did that day if you’ve never been a stay-at-home father,” he explains.

Henry lives in California with his wife and his four children. He became a stay-at-home dad per his wife’s suggestion. At the time, she was pregnant with their second son, he hated his job and his salary was just enough to pay for their first son’s childcare. Following a few months of consideration, he decided to do it and, similar to Carpenter, felt frightened in the beginning.

“It just didn’t seem like that was something that was honorable,” he explains.

But his experience showed him that it was and, determined to show to the world how great it was to be a father, he decided to create his YouTube channel, Beleaf in Fatherhood.

“Once I realized how much fatherhood changed me, I wanted to be proof of good fatherhood for other people,” he explains.

For example, in a video posted one year ago in his channel, he explains the importance of teaching Black children how to swim. Talking in a confident and reflexive tone, Henry dives into the history of the relationship between the Black community and the water, from the days when slaves died in the ocean after being forced out of their homelands, to the segregation of swimming pools in the United States. While he speaks, a meditational song plays in the back and images of his children learning how to swim flash on the screen.

“I want the water to be a place of peace for my children,” he says. “I want them to go to the beach and feel amazing in their beautiful Black skin and not be afraid to dive into the ocean.”

When his wife got pregnant with their daughter, she decided that she wanted to become a stay-at-home mother to raise their daughter and asked him if he could go back to the workforce. Henry did so by making his YouTube channel into a mentorship company for fathers also named Beleaf in Fatherhood.

“We mentor and create resources for fathers and show proof of black family life,” he explains.

He doesn’t sugarcoat though. Henry mentions that, when his wife announced that she wanted to become a stay-at-home mother, he was scared. They didn’t have any insurance and didn’t have any consistent guaranteed income, which forced him to mass produce content at a rate he had never done before eventually landing on the company.

“I didn’t know that I had the ambition and drive and work ethic that mustered up,” he explains.

The personal growth that Carpenter and Henry experienced after breaking from the idea of being their family’s breadwinner is an illustration of how being open to diverge from what is considered masculine in western cultures can be positive.

If today, people feel more comfortable challenging gender norms, there is a lot to thank the LGBTQIA+ community, Scott Melzer, a professor of Sociology at Albion College in Michigan, explains.

“They’re challenging these ideals that being born male or female automatically leads to a certain set of behaviors and attitudes,” he says.

Because he is not LGBTQIA+, he can’t speak on behalf of the community, Melzer concedes. However, as a sociologist, he says that gendered ideals such as what it means to be a man, a woman, queer or straight are not universal to cultures and times, meaning that they are subject to change.

When Leila Rupp went to college, there was no such thing as women’s studies, gender studies or sexuality studies. Rupp, who is now the graduate dean at UC Santa Barbara and faculty member in feminist studies at that university, explains that the field of women’s studies started being introduced in academia in the late 1960s and that sexuality studies was introduced even later. The first class she ever taught about queer studies took place in the 1980s.

The role that the queer community plays in breaking gender stereotypes is “absolutely central,” she explains. To say that something is “for men” or “for women” is outdated not only because society got past its gender stereotypes, but also because today we understand that men and women are not the only possibilities.

“Gender is something that’s very fluid and is also very contingent on the cultures in which we live,” Rupp says.

Rupp is also married to a woman, who also works as a sociologist. And when it comes to queer couples, she explains that there are no assumptions regarding who should perform each role. Couples need to decide the roles each party will play based on their skill and preferences rather than society stereotypes.

“Heterosexual couples should be doing the same thing,” she proposes.

Raised on the East Coast, Ruth Glass is a queer stay-at-home mother. Today, she lives in Evanston, Illinois, with her wife and her toddler. She explains that the decision of having a stay-at-home parent came from the desire to have work-life balance and spend time with their child. She says though that a lot of people were surprised that she would be the stay-at-home parent because she wasn’t the one who carried the child.

If there are no assumptions in queer couples, as Rupp said, Glass’s family is an example of that. In the past, she and her wife took turns as the family’s breadwinner. They concluded that Glass would be the best stay-at-home parent in her family based on her skills, again as Rupp mentioned it should be the case.

“I have a background working with kids,” Glass explains.

One of Glass’s main challenges was finding a community of other queer parents. And even near a big city like Chicago the resources are sparse.

“I do think that there are elements of queerness that really lend themselves to kind of a big life transition like this,” she explains.

As part of his research, Melzer, from Albion College, wrote a book named Manhood Impossible in which he investigates what happens to men when they fail to keep up with physical and financial manhood expectations in the U.S. Part of his research involved interviewing stay-at-home dads. He found out that whether stay-at-home dads felt happy and successful relied on a few different factors. One of these was how much support they received from their partners.

“If the partners are aligned in expecting the stay home dad to serve that role, then it’s a much smoother, easier experience and more enjoyable,” he says.

Ruth’s brother, Andrew Holmes, is also a stay-at-home parent and has a lot to thank his wife Olivia Holmes in his growth process.

During a warm spring afternoon, they exchange laughs as they watch their two-years old daughter Kendra play in the imagination playground in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. She runs across the black and white bridge that connects two parts of the little wooden castle.

“She just learned how to do this one,” Andrew says, pointing at the bridge.

Their outfits match, in what seems like an accidental choice of primary colors. Andrew wears a light red polo shirt, Olivia wears a bright red dress with a light blue denim jacket over it and Kendra wears a white T-shirt with a yellow raincoat.

Kendra’s familiarity with the place is clear. She can name the dragon statue at the entrance and knows in which structures she wants to play. At one point, she just wants to run between Olivia, her mother, and Andrew, her stay-at-home father.

Andrew became a stay-at-home dad in 2020, during one of the worst phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Kendra had just been born and he, who had just graduated from a masters program, was actively looking for a job. They lived in Nashville, Tennessee, at the time. He explains that they didn’t feel safe sending their daughter to daycare while vaccines weren’t out yet. The solution: he would stay home to take care of her.

“We had to make sure she was safe,” he says.

Olivia quickly jumps in, adding that Andrew already expressed the desire to be a stay-at-home dad in the first years of their relationship, when they were undergraduates in college and the pandemic was years away from happening. That’s when he unveils another layer of his motivation, explaining that he is the son of a stay-at-home mother.

“I valued her being there,” he says.

Andrew was raised Mormon, a religion in which gender norms are rigorously imposed. He explains that, in Mormonism, the value of nurturing is taught as a way to justify why women have to stay at home and take care of the kids. As a young boy, he internalized this belief and decided that he too wanted to nurture his child as much as possible.

“I think I just sort of took into that even as a boy,” he says.

His sister Ruth confirms that she was also very praised within the family for taking care of her siblings and that this was a way to enforce gender stereotypes on her. She tells that she grew up in a Mormon church named The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints where she attended what she describes as “almost like a Sunday school.” When the kids turned 12, she explains, they were separated into two groups: young men and young women. These groups performed different activities once a week.

Andrew says that he started to break up from the masculine stereotypes enforced on him by his church when he went to college and his “eyes opened.” That’s when his now wife, Olivia, helped him break some of the preconceptions he had.

“I think a lot of our early relationship in college was around Andrew exploring what he wanted for his life and a lot of that was about his faith at the time,” Olivia remembers.

Andrew also credits her as a very supportive partner in the sense of being understanding of his limits. For example, he has a chronic health issue that can be debilitating and says that Olivia was never judgemental of that. His mother, who also has the same issue, didn’t receive much support from his father.

But why do men get credit for staying at home with the kids, if women have been doing this all along, Liz Montegary, Chair of the Women, Gender, and Sexuality studies department at Stony Brook University, questions. This is because people believe this to be their natural role.

“[Labor at home is] not even really [considered] labor, because it’s just naturally what she’s supposed to be doing,” she explains.

In recent feminist studies, scholars have divided labor in two: productive and reproductive, Montegary explains. Productive labor is the labor done out in the world, the one that comes with a wage. Reproductive labor is done at home. It consists of reproduction and of raising. For her, while it is great that people started to give value to the stay-at-home job, it is unfortunate that it took men to do it for this to happen.

“When we have a stay at home dad, does this change the way that we think about the labor that happens in the home? Do we start thinking that’s more valuable?” She questions.

Glass shares that, in her experience, it depends on who she is talking to. There are multiple stay-at-home parents in her family, which creates a “shared family philosophy” that values the job.

“I think that speaking in my extended family, like my brothers, my sister, my in-laws, they all have a very clear understanding of how much work it is and how valuable that is,” she says.

On the other hand, she agrees that, generally speaking, men tend to receive more credit for performing the stay-at-home parent role, whereas women are expected to do so.

“It’s just kind of run of the mill,” she explains.

Glass adds though that, regardless of who is doing it, caregiving isn’t valued. She says that, from a capitalist perspective, caretaking isn’t considered productive since it doesn’t bring any income or any profit in the short term. She wishes that focus went towards allowing families to make decisions based on what’s best for them and their values.

“That’s where I sometimes feel like we get caught up a lot in kind of this gender binary of moms versus dads, instead of thinking about the way our society is structured,” she explains.

Vandello — alongside his colleague at USF Jeniffer Bosson — developed a theory named precarious manhood theory, in which they argue that manhood is a precarious social status.

“[Manhood is] a status that is earned and, in order to earn it, you have to do something, you have to achieve it,” he says.

Based on his and Bosson’s research, manhood is precarious because, once earned, it can also be lost. And this instability forces men to constantly prove and reprove that they still have it.

“The result of this is that I think a lot of men have a lot of anxiety about their status,” Vandello, from the University of South Florida, says.

This pressure to maintain manhood intact can have consequences in all areas of life, including the workplace.

In one of the pictures posted on his Instagram feed, Jared Hoke is posing in the middle of an underground parking lot. He is shot from below, with a focus on his beige Air Jordan 1’s. To his right, the shining lights coming from a long line of rectangular lamps reflect on the wet black concrete, creating a blinding beam. Jared stares at it with his sunglasses on, his hands hidden in the pockets of his black leather jacket and his knees slightly bent, throwing his hip upfront and his body backwards. Nearly no cars can be seen, as if the space had been closed for the shooting of a fashion campaign. His deadly serious expression shows that he is there to make a statement.

The post itself is a carousel of five pictures, each one of them focusing on a different garment. The cover picture shines every 12 seconds while a trap beat plays in the background. His full name, Jared Amir Batiste Hoke, is stamped in the middle of the picture in white capital letters. The location says “Manhattan, New York’’ and the captions reads “Wake Up F1lthy.” There is no room to question the artistic vibe of it.

The modeling agency, the fashion magazine and the two digital fashion galleries tagged in the post would lead you to think that Jared lives a life full of fame, glamor and money.

If you know Jared, you know that he has a passion for modeling and for fashion photography. You know that, when he is working as a model, he can be himself, he can show some of his sensitivity. You know that, for him, fashion is an art we all engage with on a personal level on a daily basis.

However, if you know Jared, you also know that, besides being a part-time model, he is a web developer and a student at the Columbia University Medical Program. He never got paid for a modeling job. It took him five years of independent work for him to finally feel comfortable with himself and that, only after that, he started reaching out to casting calls, modeling agencies and auditions. You know that he is not seeing a huge leap into the professional modeling world. You know that he believes that web developing and medicine, male dominated fields, are way more toxic than modeling. You know that he feels like, to work in medicine and web-developing, he has to fit a certain stereotype that he describes as “somebody from the 60s” who wears a suit and a tie and has short hair.

“I think one of the major differences between the two fields really is accepting people for who they are,” he explains.

In a way, modeling is more inviting than web development and medicine for him. He remembers a recent call where he felt supported and was complimented in his outfits, even though they were leaning on the side of feminine. On the other hand, in the male dominated fields he works in, he senses a lot of negative competition.

“It feels very sort of rigorous and puts you down competitively, no one’s really uplifting each other,” he explains.

Recent research suggests that men are more likely to engage in toxic behaviors in the workplace such as mistreating coworkers, withholding help and lying for personal gain if they think their identity is being threatened. The research, which was originally published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes in December 2021, draws from Vandello and Bosson’s precarious manhood theory to illuminate the nature of gender threats and their consequences in employee behavior.

Keith Leavitt, professor of management at Oregon State University and first author in the original paper, mentions Uber as an example of a company that was known for pushing a “competitive frat boy sort of culture” over its employees. He explains that such culture has negative consequences for women and for men as well.

“It also leads men to feel insecure and start, you know, enacting these things that continue to create a bad system,” he says.

Leavitt also explains that work is a space of validation and, because of that, men who feel like their identity is being threatened at work might feel like their autonomy is being constrained. In that case, engaging in harmful behaviors can serve as a way to revalidate themselves.

“They’re more likely to lie, cheat and steal, if that’s what’s available to them as a way of sort of demonstrating their autonomy,” he says.

Terms such as toxic masculinity or fragile masculinity might feel gender threatening to men, which, in turn, perpetuates the problem. In that context, precarious manhood is a better option.

“By labeling masculinity with words like toxic, it may be perceived by some as a threat to their gender identity,” Luke Zhu, a professor of organizational studies at York University in Toronto and one of Leavitt’s co-researchers, says.

Zhu also clarifies that these results might not replicate in other cultures. When the press release for his research came out, one of his colleagues at York University questioned what the results of this study would have been in cultures that don’t appreciate masculinity as much as the U.S. does.

“I thought that was a great question, because now we’re talking about the national culture aspect of this finding,” he explains.

In today’s U.S. society, men are expected to do well in work, to be the breadwinners of their families and that’s why, from a stereotypical perspective, work matters so much for men to earn and re-affirm their social status, Zhu says.

“Whether you’re successful at work is a critical indicator of how manly you are,” he confirms.

However, this is a stereotype and that living up to it is demanding both for men and women, Zhu explains.

“Sometimes it works better, if, you know, the wife is the breadwinner,” he says.

That was the case for Carpenter’s family. Becoming a stay-at-home dad and breaking from what he called “traditional gender thinking” opened a world of possibilities for him and his family. He realized that his masculinity was not up to debate and that masculinity, the word that once scared him to the point he threw up in his office’s urinal, was, in fact, almost nothing.

“It is [just] a word.”