In the shadow of Russia, Moldova is a country worth preserving

Few countries have been as targeted by Russian disinformation campaigns as the Republic of Moldova, but this phenomenon has not gone uncontested. A gutsy think-tank with a bulldog as its logo is doing everything it can to expose Russian interference in Moldovan affairs.

WatchDog’s tightly-knit team works out of a small warren of offices by a rose-filled courtyard in the center of Chisinau, the capital. A Russian cultural center, thought to be a hub for Russian operatives in the country, is just a block away.

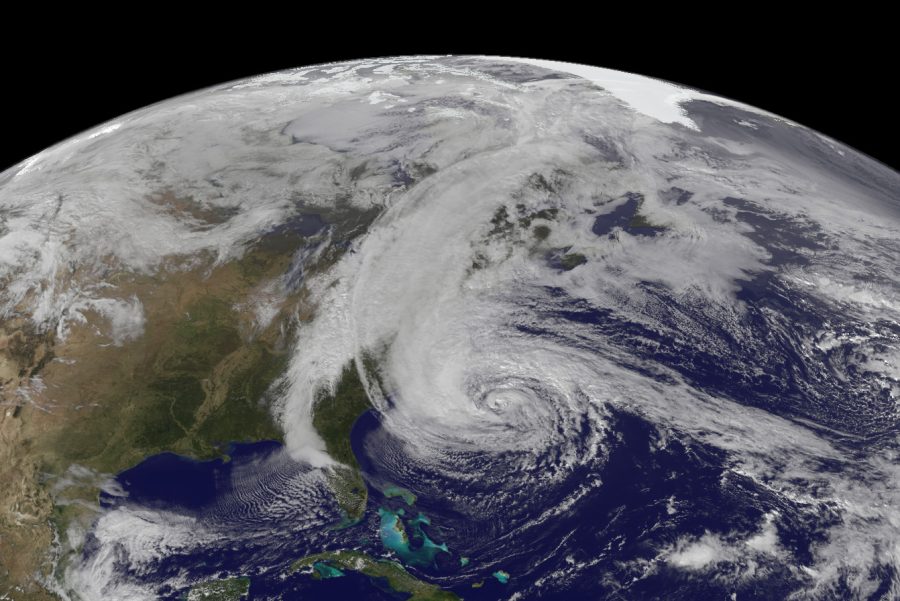

Sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine, Moldova is vulnerable to disinformation operations due to its complex history, location and Russian-speaking heritage. Had the Russian invasion of Ukraine succeeded, few Moldovans believe their country (with a population of barely three million) would have been able to withstand annexation. It has only a small military, which makes it an easy target, but it is doubtful a conflict would arise. Instead Russia has been trying to capture the country by winning the information war.

While propaganda flourishes on television, disinformation campaigns in Moldova seethe in a social media cesspool. Telegram and Facebook are among the most popular platforms in the country. The 30-plus crowd gravitates toward their content-specific channels and pages in search of discourse, debate and information. But without a trained eye, the most circulated topic of the day might just be a lie.

In February, Sputnik Moldova, a now-banned Russia-affiliated Telegram channel in Moldova, buzzed with a viral post of a seemingly official government document summoning Moldovans born from 1996 to 2004 to the Ministry of Defense. Rumors of a mobilization spread and fears of a Russian invasion were heightened as the war in Ukraine approached its one-year mark.

The Watchdog team implemented their system of early alerts, where they monitor disinformation as it disseminates in real-time and provide their findings to authorities so false news can be debunked. The defense ministry issued a statement denouncing the viral document as manipulated, contrasting it with a real example of a summons.

Historically, parts of Moldova have belonged to Romania, the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire, and finally the Soviet Union. Because of these ties, the official state language is Romanian, but a large part of the population speaks Russian, making it easier for Russia to launch disinformation campaigns. On top of that, after the invasion of Ukraine, Moldova began the process of applying to join the European Union, which Russia opposes.

The monumental task of monitoring television news and digital media is extremely time-consuming for the WatchDog team. Currently they monitor eight Russian-speaking television stations, after six others were suspended in June 2022 by the Commission for Exceptional Situations in Moldova for broadcasting blatant propaganda on the Ukraine war.

“Even though I speak Russian very well, it takes time to translate the news I track for my report,” said Rodica Prigari, one of Watchdog.MD’s media monitoring experts. Each team member forwards data from the news channels for analysis and compilation in a report, which is then dispatched to several television partners in order to improve their news coverage.

But progress within the television broadcast community can be slow. “We have several projects with them and have provided training, but the quality of the news has not improved to where we would want it to be,” she added.

The problem with Moldova’s Russian-language channels is not so much about telling bare-faced lies on air; it’s about biased storytelling and the framing of narratives, especially when it comes to the Ukraine war.

“You don’t see any images from the battlefield or bombings. It makes the war look like the special military operation the Russians want it to be,” said Prigari. “They only broadcast one story every few days about the war and it’s more like a press release from the Russian ministry of defense.”

Some political parties, like the Sor Party, have grown increasingly pro-Russia since the Ukraine war began. Headed by Western-sanctioned oligarch and fugitive Ilan Shor, the party came under investigation in May for alleged bribery during the elections for governor in the autonomous Gagauzia region, which the Sor candidate won.

“The Sor party tactic is to switch attention from the war in Ukraine to the general problems that Moldova faces,” Miscisina said. “Their narrative is that our government is incompetent, they can’t deal with the problems of our country, and the rest is all an excuse.”

In June, the Moldova Constitutional Court ruled the party “unconstitutional” and ordered its immediate dissolution after alleged destabilization attempts through Sor party-funded protests.

One of the popular tropes of Russian propaganda and disinformation is that Moldovan president Maia Sandu is a Western puppet and that NATO is trying to drive the republic into war in Ukraine. According to Miscisina, Russia-backed troll farms boost viewership of these themes through sponsored videos on Facebook and other social media.

The first step to combating disinformation for Watchdog starts with monitoring “everywhere we see that the disinformation is spread,” Dragomir said. But Watchdog also has its own presence on all major social media platforms. It releases videos, either self-produced or clips from television segments, on topics ranging from corruption to the energy crisis.

Video content is presented in a direct manner, either with experts in conversation with a presenter or talking right to the viewer. A scroll through the Watchdog.MD Facebook page shows a balanced amount of Romanian and Russian-language segments, emphasizing their mission of being far-reaching and effective across all audiences in the country.

Younger Moldovans tend to be more media savvy and are better at detecting disinformation than the 30-plus crowd that their videos target, but their efforts are “not enough to cover it all,” Miscisina admitted. She spent four months in 2022 studying the impact of Russian narratives about the Ukraine war at Stony Brook University’s Marie Colvin Center for International Reporting on a community solutions fellowship from Irex, the Washington-based global education specialists.

Amelia Solomon, a third-year international relations student at State University of Moldova, said her county’s population is divided between being pro-democratic and stuck in older, Soviet beliefs.

Many people in post-Soviet countries have issues with trusting mass media after the fall of the USSR, when everyone realized the content presented on television was a lie, said Anna Glushko, a reporter for Prime TV in Moldova and a correspondent for Germany-based network Deutsche Welle, who attended a training session with Watchdog in May.

Most would rather trust the opinions of a neighbor or something they read on social media, Glushko added. However, Moldovan journalists are at a special advantage in deciphering information coming out of Ukraine because of their Russian, and to a lesser extent their Ukrainian, language skills.

“It’s harder for our Romanian colleagues who don’t have those language skills because they have to rely on English sources for translation,” Glushko said in Russian. “It becomes a game of broken telephone.”

Monitoring television and social media, producing reports and being one of Moldova’s leading think tanks is a round-the-clock job. The Watchdog team says their drive lies in being of service to the public.

“You want to be a part of the change, you want to help people understand, you want to increase media literacy and increase the resilience of the population,” said Dragomir. “We feel that we have an impact. And we will continue to do it.”

The first thing Irina Stryapko does in the morning is contact her loved ones to see if they’re alive. “On any given day I could lose them, because this is war,” she said with a fortified face. The tears welling in her eyes betrayed her composed demeanor.

Stryapko is one of 848,800 Ukrainian refugees who crossed the border into the Republic of Moldova after Russia’s invasion in February 2022, and among the 110,854 who stayed on. Her beachside hometown of Odesa functioned as the Miami of the Black Sea for Ukrainians and Moldovans in peacetime, and lies only three hours by car from her new home in Chisinau, the Moldovan capital.

Her current reality differs drastically from the lives of those she worked alongside as a journalist back home. “My friends, half of my colleagues — journalists, photographers went to defend the homeland,” Stryapko said in crystalline Russian. “Instead of cameras and microphones, they took up arms to shield the nation.”

It’s rare for refugees to retain their former professions in a new country. That wasn’t the case for Stryapko, who is working as a news presenter at TV8 — a pro-democratic Moldovan television network with Romanian and Russian programming. In addition to being a Russian-speaking anchor, she hosts a talk show called “Good evening, we are from Ukraine,” which sheds light on issues Ukrainian nationals face in Moldova and examines internal discourse around refugees.

At a conference table within the TV8 studios, the 36-year-old sits upright and extended, a swan-like posture that comes with years behind the anchor desk. Her sharply-winged eyeliner, straightened wheat-colored hair and stretchy black midi dress conflict with her slippers — an off-camera, camera-ready look. She chuckles as she reflects on the “shock” the Moldovan audience must have felt with her sudden appearance as “some Ukrainian” who is not only a presenter but now has her own show. Her motto?

Life moved fast for Stryapko since the onset of the war, but she initially never intended to leave Ukraine. Doubling back then as a journalist and a head of a PR firm, she distracted herself with work and admitted she wasn’t as distraught as those around her when it came to impending danger. After the first few months of the invasion, both companies shuttered, leaving her unemployed. That’s when she decided to take up a friend’s offer to go on a getaway for a few weeks to Moldova.

A colleague, who knew of Stryapko’s Romanian language skills and of her recent arrival, recruited her for a position at TV8, where she soon felt “at home.” She’s now past her one-year mark with the station. “On the second day, I found an apartment and on the third, I was already at work.”

The refugee crisis is entering a new stage given the prolonged nature of the war, one that is directed at resettlement instead of immediate, temporary relief. Ina Taci, head of the Moldova branch of the International Rescue Committee (IRC), is working on finding refugees long-term employment so they may have access to housing, education and mental health services to build the next chapter of their lives.

Tcaci, who previously worked for the United Nations, recalled wanting to do more for refugees after seeing the “worst image” in her life while volunteering at the Moldova-Ukraine border at the start of the war.

“An early morning in March, there were some 3,000 people in line. Some died of cold in their cars, others were barefoot or wearing flip-flops,” she remembered as she pointed to the goosebumps springing up her arm. “One of the most shocking things was that none of the children under five were crying.”

Since opening a year ago, the IRC Moldova branch has established “healing classrooms” focused on the social well-being of children affected by trauma, and has provided employment to 50 refugees, she added. The IRC also works to find inclusive housing for LGBTQ groups disadvantaged by Moldova’s issues with homophobia.

Like many Moldovans, Tcaci hosted refugees in her home during the first waves of migration. She says the profile of refugees coming out of Ukraine differs from those in other countries where the IRC works. Ukrainian refugees tend to be educated, middle class and consist predominantly of women, children and the elderly because of Ukraine’s martial law barring most men from leaving, she said.

“Americans who know anything about Moldova know it’s a small country with a big heart,” Kent Logsdon, US ambassador to the Republic of Moldova said in a personal meeting in his office at the embassy. “You could see that when Moldovans opened their homes to refugees at the start of the Ukraine war, before the international community could help.”

With blue and yellow balloons in hand, Natalia Bibikova watches as one of her daughters gets face paint in a square outside a Chisinau art center. It’s the last day of the center’s “Ukrainian Film Days,” a three-day film festival concluding with a screening of a children’s cartoon. The kids play games with the whimsical, sequined hosts of the event as parents and guardians, mainly women, watch from the sidelines.

Bibikova, a single mother, fled to Moldova on February 27, 2022, just three days after Russia invaded Ukraine. Coming from Odesa with her two daughters, who recently finished second grade, she chose to stay in the country so they could continue their education in Russian as they did back home. Nestled between Romania and Ukraine, Romanian is the official language of landlocked Moldova, with Russian as a recognized minority language.

She says she’s enjoying the newfound free time she has with her girls after leaving behind her office job in Ukraine. In the beginning, she was living “day-by-day, month-by-month.” After over a year of living abroad, she’s only now “processing what happened.”

The desire to go home is strong. When watching the news, Bibikova recalled her daughter asking:

Oksana Sayenko, with her toddler on her hip, echoed a similar sentiment. Sayenko, who moved to the republic in May from Kyiv Oblast with her husband and child, said the situation is “mentally challenging” and that she would go home if she could. She wants to see more events conducted in Ukrainian, rather than Russian so that the children could at least know their “mother tongue,” she expressed.

For Bibikova, the hardest part of living in Moldova is the uncertainty with housing. She lives in a “state of fear” because she doesn’t know how long her current housing situation will last — she initially worried she’d be kicked out after her daughters’ school year ended. An organization currently covers her housing, but if that were to end, Bibikova says she would have no choice but to move back to Ukraine since she cannot afford to pay rent herself.

Ukrainian nationals can apply for Temporary Protection in Moldova which offers a right to work, healthcare and possible housing accommodation within the country. It’s not a popular option. Out of the over 110,000 refugees recorded in Moldova, only 7 percent are registered for temporary protection.

According to Tcaci, the lack of registration is partly because most leases are done “illegally,” with landlords and tenants alike not wanting the hassle, and taxes, of registering them on the books. Temporary protection also only allows for 45 days spent outside of Moldova, with recipients obliged to report returns to Ukraine, something that conflicts with many who go back and forth between the border to see their families, she said.

While Bibikova and Sayenko agree the Moldovan response to the refugee crisis has treated them well, Bibikova says attitudes from individual Moldovans could be sour. They call us “Banderites,” referring to the Nazi-affiliated Ukrainian nationalist Stepan Bandera, and claim, “This war is your fault,” she said.

As a post-Soviet state, Moldova is vulnerable to pro-Russia disinformation and propaganda that stokes internal issues with the current pro-European administration. In a two-part episode of “Good evening, we are from Ukraine,” Stryapko highlighted the “information war” in Moldova by investigating a viral TikTok video of a gas station clerk telling the Romanian-speaking videographer to “drop dead” in Ukrainian.

The text “*Ukrainian flag emoji* are making a mess in Moldova” was overlaid on the video, with users commenting “Send them home” and “You should have given more thought to who you accept into the country.”

After investigating the incident, Stryapko discovered the gas station clerk was not a refugee and was in fact born in Moldova, and that the short clip only showed the climax of a longer exchange where the customers provoked her.

The country is also one of the poorest in Europe. In 2020, the International Organization for Migration estimated almost a quarter of Moldovans lived abroad because of the lack of well-paid work opportunities within the country. Because of this work-related diaspora, remittances sent back home made up 15 percent of the country’s GDP in the same year.

The presence of Ukrainian refugees in the country’s small population of just over three million adds competition to the job market as the republic grapples with poverty, Tcaci said. The poverty rate in Moldova was 24.5 percent in 2021, according to the UN Development Programme.

Gathered at a park table in central Chisinau, Diana Calmatui, a 23-year-old Romanian speaker, said the number of refugees is “huge” and that “they can take our jobs.” She added that they can “cause trouble” and aren’t comfortable with what Moldova has to offer them.

If you told Silvy Rusu this war would happen five years ago, she would be “dumbfounded.” Sitting on a park bench with a girlfriend, the 58-year-old Moldovan believes “there is space for everyone” in her homeland. Rusu, who works as a caretaker in Italy and recently returned to Chisinau for a break, remembers the bygone Soviet era when “we were all one country.”

“My soul hurts,” she said in Russian, adding that she maintains relations with people from various post-Soviet republics, including Ukraine, but that they avoid political discourse. “We all once ate from the same apple and celebrated together. Now it’s like a wolf attacking a bunny…I don’t know if our grandchildren will ever experience that kind of friendship.”

Organizations like Moldova for Peace work to support refugees while giving back to the local community. Since February 2022, a once-vacant lot in a film studio on the outskirts of Chisinau has been transformed into a labyrinth of stacked boxes with some labeled “UNICEF.” Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” echoes through the lofty hall as a queue of displaced Ukrainian nationals forms to receive care packages.

An estimated 5,000-6,000 refugees are weekly beneficiaries of packages ranging from food, hygiene and school products distributed at the warehouse. Support comes from international partners, including the United Nations Relief Fund, to ordinary Moldovans who donate clothing and shoes. Qualified recipients can fill out an online form every 10 days specifying their family size and product requests before receiving a message when it’s time to pick up.

Pavlo, from Odesa, arrived at the distribution center with his five-year-old son Vlad. He said he mainly needs diapers for his toddler at home with his wife but that he’ll “take whatever,” as the packages “help a lot.” The 43-year-old works for Disney Cruise Line and is the only wage-earner in his family.

With a limited budget and supply, the team can’t afford to make individual exceptions. One mother, who said she needed diapers for her child who wets the bed, was denied her request because the child was over three years old, the cut-off for diaper distribution. Organizers say they’re constantly scouting new partners to ensure a seamless flow of products.

Natalia Rahmistriuc, the warehouse coordinator, hopes to go beyond aiding Ukrainian refugees. “We buy from Moldovan businesses, vendors and employ Moldovans,” she said. Rahmistriuc and her team of workers and volunteers foster community-building through open-invitation packaging events with a DJ and refreshments on Saturdays, and by hosting soccer games between Moldovan and Ukrainian teams.

Towering around seven feet, one volunteer stands out from the rest. But perhaps what’s most shocking about him to the refugees he meets is his Russian nationality.

Ivan, a pseudonym for the 24-year-old, was a professional basketball player since the age of 15 and left Russia when he felt he did not have a future in the sport. Encouraged by his father, he came to Moldova in July of 2022 to support “the other side” and said he found his purpose in volunteer work.

While Ukrainian refugees are surprised to learn where Ivan is from, he says he’s never experienced a negative reaction at work. Hearing their stories left him feeling “numb and overwhelmed” during his first months in the republic. He said:

After the deaths of three close friends, Stryapko said she learned the scariest thing about war isn’t losing your home and livelihood. It is when, “Your loved ones are on the frontlines and they aren’t reachable for days. God forbid they don’t come back.”

“In the 21st century, we’re going through something in the center of Europe that can’t even be replicated in movies,” she said.

Reflecting on Moldova’s “colossal” undertaking as a transit and relocation hub for refugees, Stryapko said she’s “grateful to every single person” who is part of the effort. Seeing tens of thousands of Moldovans gather at a pro-European Union rally in late May made her “very happy” that the country is moving in a progressive direction.

“The appetite of the dragon is inexhaustible,” she said. “But if, God willing, Ukraine wins, Moldova also has a good future.”

“We have to stop this war and save humanity. As pathetic as that sounds, that’s the reality. It’s a wound that will never heal but it’s our destiny.”

On June 1, 45 European world leaders landed in Chișinău, the capital of Moldova. It was the biggest international gathering the tiny republic had ever seen. They had flown in for a European political community summit, an event that fostered discussions on joint efforts for peace, climate action, and stronger relationships between European countries.

Considering that Moldova has a population of barely three million, smaller than most US states, and one of the lowest GDPs in Europe, it was a vote of confidence in the nation’s future. Moldova, which lies between Ukraine and Romania, matters more than ever to the geopolitics of Europe.

It is a country that has been passed around in ownership for hundreds of years, having been a part of Romania, the Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire, and the Soviet Union before finally declaring independence in 1991. More recently, Moldova has been in the public eye following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. President Maia Sandu and prime minister Dorin Recean have both accused Vladmir Putin of trying to destablize the country. In March this year, the government arrested a group of alleged infiltrators for plotting to create unrest..

Directly following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Moldova began the formal application process to join the European Union. In June 2022, it gained official candidacy status alongside Ukraine. The move has created further tension between Moldova and Russia, with the Kremlin accusing the country of falling into “anti-Russian hysteria”. As relations have become more strained, Russian political and media interference in Moldova has intensified.

Igor Botan, the executive director for the Association for Participative Democracy (ADEPT) and an expert in the Moldovan electoral process, argues that politics in Moldova does not divide along conventional lines. “It’s not a competition of ideas or policies. It’s pro-Russia or Pro-Europe,” he said.

This type of battleground in politics makes it easier for Russian interference in elections. “Moldovan democracy is kind of fragile,” Botan added. The country is vulnerable to Russian-backed political parties in parts of Moldova that have been historically loyal to Russia such as the autonomous region of Găgăuzia and breakaway province of Transnistria.

The recently-banned Shor Party, founded by the fugitive, pro-Russian oligarch, Ilan Shor, succeeded in securing the election of their candidate, Evghenia Gutul, as governor of Gagauzia in May. “Ninety-five percent of Găgăuzians support Russia in the war,” said Botan.

The media outlet, Nokta, based in Comrat, the capital of Găgăuzia, has insight into Russia’s influence in the region. “Here in Găgăuzia, Russians dominate. They play the game they want to and how they want to,” said Nokta editor Mikhail Sirkeli. Parties like Shor splash plenty of cash around, he alleges. “They pay 15,000 lei ($835) a week to be an activist for them. It is nothing to them.” Botan also accuses politicians of buying votes. “They’ll say ‘vote for me’ and I’ll give you $20.”

It would be difficult to prevent all Russian interference in Moldova, but Botan believes that the country is headed in the right direction. “Joining the European Union would help with the kind of legislation we need. For us it is the dream. We would be given funds by the EU, and of course it would be very stimulating for business, education and medicare.”

However, getting people to care about joining the EU has proved difficult. The average monthly wage in Moldova is 11,486 lei, or approximately $649 USD. This low wage has forced up a third of Moldovans to leave the country in search of work abroad, where they also risk exploitation and are often paid less than the average wage.

Eugene, 31, who lives just outside Chișinău, says, “My friends don’t care about politics, we just want to work.” He has been lucky enough to find remote work in Moldova: “I do IT for a company in Austria,.”

Many Moldovans, such as Eugene, hold a Romanian as well as Moldovan passport, enabling them to work and travel throughout the EU. Yet while his friends understand the value of being

in the EU, they remain apathetic about politics. “Young people here don’t really protest. We just think that all politicians are corrupt, so it doesn’t matter who we vote for.”

When the war broke out, many Ukrainians fled to their closest neighbor. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, over 400,000 refugees entered Moldova last year, and while many left the country soon afterwards, about 100,000 stayed. The Moldovan people welcomed them with open arms, sometimes to their own detriment. Ina Tcaci, head of the International Rescue Committee in Moldova, said, “Many families would support a refugee or group of refugees as long as they could. They would run out of money trying to help them.”

With international aid, support for refugees has stabilized. Roughly 100,000 Ukrainians remain in the country. “What’s unique about this situation is that these refugees are mostly educated and middle class people. They know their rights, and the Moldovan government has very good protections for them,” Tcaci said.

At a repurposed film studio in Chișinău, Natalia Rahmistriuc, a warehouse coordinator for Moldova for Peace, does her best to provide for the basic needs of refugees. “We prepare between 1,500 and 2,000 packages per week. We see between 5,000 to 6,000 people per week and 300-400 orders per day.”

For a team of around 30 volunteers, it’s a tremendous amount of work. Fortunately, there is no shortage of volunteers willing to help. “We have volunteers from all over. Even one from Japan!” she exclaimed. “In Moldova, there is a clacă. An event where we all come together to do something that helps the people. We play music and have food while we make the packages.”

The clacă does not only assist those who need physical goods, but is social as well. “Those we have already helped take part in the clacă. It helps with integrating communities. And if one doesn’t happen, people will say to me ‘Oh, no clacă this week? Why?’” said Rahmistriuc.

What may be most surprising for Ukrainian refugees isn’t the Japanese volunteer handing them baby products, but the Russian one.

Ivan, 24, who goes by a pseudonym for security reasons, is very friendly and upbeat, but has an air of solemnity as well. “My parents always taught me to help others,” he recalled. Although he used to describe himself as “anti-politics”, thinking they were “a game I don’t understand,” the war opened his eyes. “I almost couldn’t function for a bit,” Ivan said, when he first saw what the Russian military had done to Ukraine. “I just want to help people who are suffering.”

Ivan, who is nearly 7ft tall, used to be a professional Russian basketball player. He does his best to assist those that come to the warehouse, and Ukrainians treat him kindly for the most part. “People are often surprised that I am Russian and helping them. But I have never heard a bad thing towards me.” It’s because of volunteers like Ivan and many other Moldovans that many refugees are supported so well.

Pavlo, 43, fled from Odessa to Moldova with his wife and two young children in early May, 2023. The war has completely upended his life. “It’s a disaster. My mother and niece are still in Odessa. But this place is good for the children. It helps a lot.” His youngest son is less than a year old, and free diapers and other products provided by Moldova for Peace lessen the financial burden.

In an interview at the US embassy in Chișinău, Kent D. Logsdon, the US Ambassador to Moldova, said, “Americans who know anything about Moldova know it’s a small country with a big heart. You could see that when Moldovans opened their homes to refugees at the start of the Ukraine war, before the international community could help.”

Moldova is at a critical point in its history. According to Logsdon, “Moldovans felt they missed the bus when other countries joined the EU. They don’t want to miss the bus this time.” Western aid from the US and EU is helping to turn the economy towards the West and away from its former dependence on Russia.

This can be seen in the wine industry, which plays a major part in Moldovan culture and accounts for three percent of the nation’s GDP. Moldovans have been cultivating wine for almost 4,000 years, but when it was part of the Soviet Union, the art was somewhat lost. It used to mass produce cheap wine for the Soviet market, but today wine-makers are focused on exporting artisanal wines to Europe, and even to parts of the US.

The wine export sector is worth $140 million and wins international awards for its products. Moldova is even home to the world’s largest underground wine cellar in the limestone tunnels of Milestii Mici. With its already high quality wine and prospects for growth by joining the EU, the Moldovan wine industry has the potential to become a global powerhouse.

The reason Moldova matters today is fairly straightforward. It will become one of Russia’s prime targets if Russia succeeds in its conquest of Ukraine. Bolstering Moldovan institutions is an important first step towards advancing democracy in the country. The country is especially vulnerable now, while Russia is taking part in a land grab, and the world has noticed. Now it is trying to enter the global stage by joining the European Union.

Yet, based on the resilience and kindness of the Moldovan people, who are willing to do whatever they can to support their own families and responded so nobly to the Ukrainian refugee crisis, Moldova has always mattered. The world just has to make up for lost time.