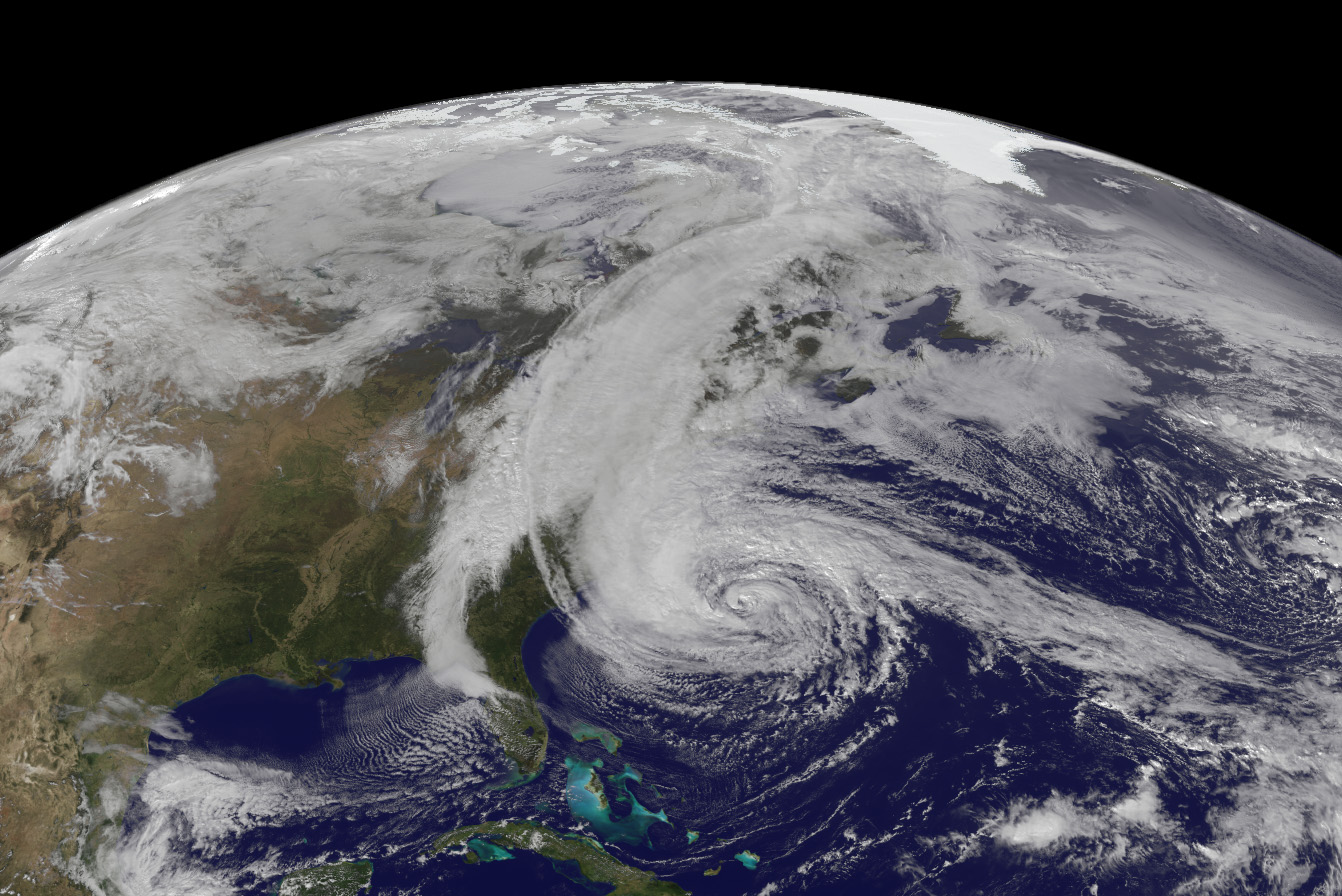

Can Long Island take another Superstorm Sandy?

Superstorm Sandy devastated Long Island 10 years ago. Humans worsen climate change, and intensify hurricanes that hit their neighborhoods. With sea level rise, coastal flooding and extreme weather, people who live, work and play near the Great South Bay are at great risk of losing their homes.

December 16, 2022

Explore the Great South Bay

Long Island’s Great South Bay system stretches for nearly 60 miles from Massapequa, through canals, to Shinnecock Bay. While each community has its local gems, the coastline features small villages, sandy beaches and fishing docks. The area has been dependent on the water to create tourism and fishing for centuries.

The beaches here are loved by the communities — and tourists, alike — with surf towns toward eastern Long Island littered with boards and wetsuits year-round. A mix of metropolitan from New York City and beach town from Montauk, the Long Island suburbs are home to pizzerias, small businesses and single family homes.

“That’s the thing about living on the south shore—so much is determined by the water ways,” said Paul Panasuk, a Massapequa homeowner. “If the oceans get riled up, the beaches take a beating!”

Ten years ago, Superstorm Sandy brought high-speed winds, heavy rains, and a 14-foot storm surge. Atlantic Ocean waters breached Fire Island and created this new inlet, a few football fields wide.

Despite the damage, this new passage between the bay and the ocean brought positive impacts on the water quality. The inlet flushed out nitrogen pollution from the bay, and allowed the formation of new marsh lands, which are healthy habitat for birds, eels, clams, scallops and other marine life.

Ten years later, this natural waterway created by Sandy has closed. Sand from other places is swept into this passage between the ocean and the bay.

“As the oceans continue to rise, and it might seem small but when you are a beach and you are getting battered a little bit higher everyday, there can be impacts of erosion,” Kevin Reed, associate dean for research in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University.

Environmentalists and some marine scientists support the dredging of the inlet to allow for the flow to continue, despite the vulnerability the breach creates for coastal flooding from extreme weather.

The bottom of the bay is like a barren wasteland,” said Tom Schultz, the director of restoration at Friends of Bellport Bay. “Sandy created an inlet that brought fresh water to the bay, which showed residents the healthy potential of life here.”

“If Bellport Bay is healthy, then the whole Great South Bay will flourish,” he added.

Meteorologist Iryna Ivanyuk analyzes what caused severe flooding on Long Island’s south shore in the wake of Superstorm Sandy a decade ago — creating a perfect storm for the breach of Fire Island inlet.

Neighborhoods along the Great South Bay and Fire Island are changing — the houses are getting higher. Streets are evolving to be protected from increasing storm surge and nuance flooding.

Houses are raised at least six feet to protect their foundations and to meet expectations for federally supported flood insurance.

“We build higher, but sometimes higher is not enough,” said John Weiburg, engineer and owner of GreenTauk Engineering, a flood zone home construction company.

Without raising, homeowners might not get assistance after the next storm.

“Flood insurance is another bill. That’s an extra $500 a month. People can’t afford it,” Weiburg said.

During Sandy, many homes were flooded to the point of losing everything. Imagine — even the best insurance policy cannot replace wedding dresses, baby pictures, and love letters soaked with dirt salt water in just a few hours.

“Climate change isn’t just measurements and data. It’s people, places, ways of life, and this generation is going to be more affected by it than almost anyone else alive today,” said Laura Lindenfeld, dean of the School of Communication and Journalism and executive director of the Alda Center for Communicating Science. “These five students found a way to tell a comprehensive and compelling story about one part of the world, how it’s changing, and what we may be able to do to adapt and survive. This is student journalism at its finest.”

Long Islanders are determined to stay here — this is home.

“My family is all around in the area, I’ve been living here for 46 years. I just really didn’t want to move. So I decided to do what I needed to do,” said Ellen McQuade, of Seaford, who is in the process of raising her home.

Meet the team

We are Stony Brook journalism students who will experience climate change throughout our lifetimes.

We started this intensive reporting project to explore how life, work and play would change along the Great South Bay, a large system of bays on Long Island’s south shore. The bulk of the reporting during the fall semester took us nearly 100 miles from the bay houses of Hempstead to hard clam restoration efforts in Shinnecock Bay.

Our project started with an idea from Professor J.D. Allen. With his help and a yearlong effort in classes taught by Professors Irene Virag, Richard Ricioppo and Terence Sheridan – and the support of a grant from the MJS Foundation – we pieced together the complex picture of climate adaption and resiliency in neighborhoods close to home.

We hope that our reporting will draw attention to climate change in Long Island communities. Our newsroom has already investigated the legacy of slavery on Long Island, which won several Hearst Awards and a national Murrow Award, and was published on WSHU Public Radio and in Newsday. The newsroom has also looked into a proposal to develop one of the last untouched green spaces in the Long Island Central Pine Barrens; and examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on among the region’s largest health systems at Stony Brook University Hospital.

For more information on our projects, including a showcase that features students work, take a look at our program at the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University: