A Turning Point For Young Americans Learning Financial Literacy

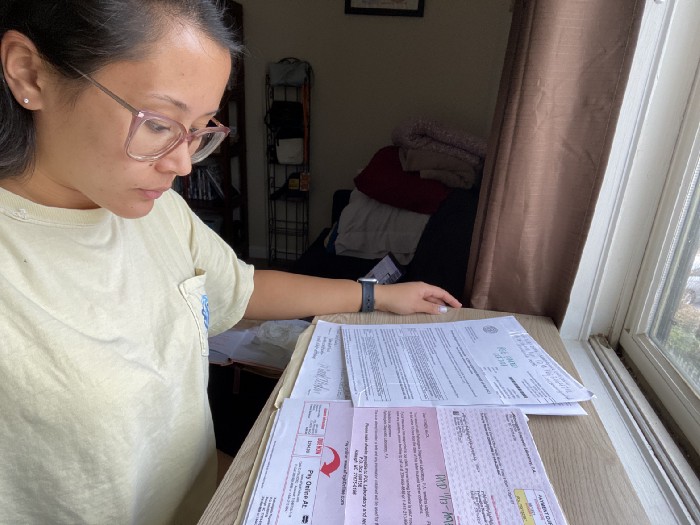

Mikaela Cohen, a 24 year-old grad student managing her finances in the COVID-19 pandemic. Courtesy of Mikaela Cohen

Financial literacy might have been a shortfall for young people in the U.S. in recent years, but since 2020, pandemic-related economic turmoil has forced young Americans to learn how to better manage their expenses.

Some economic issues were expected: the rise in filing for unemployment, and handling recovery aid, like stimulus checks. Others issues were not, including students applying for loans, and even managing the estates of a loved one.

“My dad didn’t have a will, because he was younger and thought he would live forever,” Caitlin Moen, a graduate student at Minnesota State University in Mankato, said.

Moen was a student one day, and suddenly managing many of her father’s finances the next. She took off from work and borrowed thousands of dollars in loans to take over her father’s finances from his death. Property management, claiming social security benefits, and inheritance taxes were a few of the major responsibilities Moen took over as a Millennial.

Even before the start of the pandemic, two dozen states have considered legislation to improve financial literacy education to tackle rising student loan debt, and other economic inequalities.

“I believe before the pandemic, I believe during the pandemic and after financial literacy should be taught,” Tim Ranzetta, founder of Next Gen Personal Finance, a nonprofit group that creates free courses and funds training for high school teachers.

Next-Gen created “Mission 2030”, a goal that would allow every U.S. high school student to have taken at least one semester-long personal finance course — for a generation with limited fiscal training and too much at stake.

What is financial literacy?

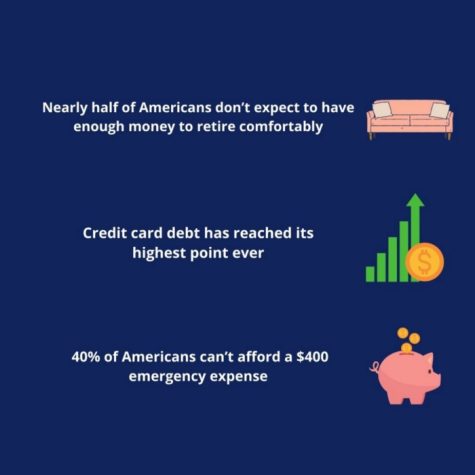

Financial literacy is the ability to understand and effectively use various skills to make informed decisions, including personal financial management, budgeting, and investing. It’s the foundation of learning about money, which U.S. adults struggle with regardless of age. Twenty-one percent of Americans do not set aside any money for short or long-term goals, according to Bankrate’s most recent Financial Security Index survey in 2019.

Someone who is “financially literate” has a good understanding of their debt, loans, and managing credit. They also may partake in financial hobbies like investing in stocks and plan their monthly spending to stay on top of bills.

They also don’t live paycheck to paycheck, as 78% of Americans do. Young Americans are over $1.5 trillion in debt. But Gen Z is more woke to managing their finances, and the economic hardship of a pandemic could be to blame.

States progress

According to the Council for Economic Education, which encourages economic and personal finance education in kindergarten through high school, at least 21 states require high school students to take a course in personal finance — an increase of four states since 2018.

Gen Z is the generation most likely to have participated in a financial education class or program; but this was most likely in their secondary and higher education.

“It’s not just about getting a formal education, they also need to learn about how to handle their money properly, their debts,” Ganesh Pandit, accounting and law professor who teaches Jovia’s Financial Literacy Workshop at Adelphi University, said.

An annual study by the 2021 TIAA Institute-GFLEC Personal Finance Index, a tool created to measure the readiness of U.S. adults to make sound financial decisions, shows most people are ill-positioned to make appropriate financial decisions due to poor financial literacy. In the latest survey, respondents only got half of the questions correctly on average.

The TIAA also found that 39% of Americans say the economic uncertainty created by COVID-19 has motivated them to increase their financial literacy, this feeling is significantly more common among Gen Z.

- Gen Z (52%)

- Gen Y (48%)

- Gen X (44%)

- Baby Boomers (29%)

- Silent Generation (20%)

Mikaela Cohen was one of the Gen Z Americans who reflected on her economic hardship in lockdown. With extra time on her hands, she began to realize what finances needed the most attention as she finished up school.

“I was just coasting,” Cohen, a graduate student at the University of Georgia, said, “then I got to my senior year and just remember thinking… ‘oh no, what, or how am I going to pay off my credit card or even make my minimum payment on my credit card.”

Race and low-income communities economic education

When it comes to financial education in schools, Black and low-income communities face hardship. The 2021 TIAA index found that Black adults are behind whites when it comes to financial literacy.

Ranzetta with Next Gen said 1-in-5 students get a personal finance course before they graduate. In communities of color, it’s 1-in-13, and in low-income communities, it is 1-in-14.

“The places where you could argue it could benefit people greatly are the ones who are getting the least of it,” Ranzetta said.

Adult Americans answered only 50% of the TIAA indexes correctly, on average. Whites got 55% correct, while Blacks answered 37% of the questions correctly. Hispanics also lagged, scoring 41%.

When it comes to educational programs, less than 12% of students are required to take a stand-alone personal finance course to graduate high school, outside of the six states that mandate it.

When it comes to Black and Brown students, it drops to 7.4%. Of low-income students, 7.8% are required to take the class.

“Many people are poor not because they don’t have the money handling skills, but because they don’t have the infrastructure in their hands,” Pandit said.

Why are young adults being targeted?

Ranzetta mentioned most young adults have had the same bank account since they were children, and professionals say this is not an accident. Even apps used daily like Venmo and CashApp have an investing section to help students put money into the market.

Ranzetta with Next Gen also said Gen Z is getting 40% of financial advice from TikTok. Financial literacy tends to be low within all five generations, but specifically Gen Z.

He said financial literacy should be introduced due to an increase in bank apps targeting consumers to younger crowds every year. This comes as hobbies like investing are compounded over several years since there’s no specific age when to start investing.

“Young people love risky behavior, and what’s riskier than getting in the Robinhood App and saying let’s trade crypto today,” Ranzetta said.

On the flip side, other instructors encourage young investors to not take charge unless they have the money first. Pandit emphasizes saving as the number one rule in his workshop for young students learning about financial literacy.

“You can’t be paying 11% interest on your debt and then 8% in the stock market in mutual funds, that doesn’t make any sense,” he said.

Some college students may invest in partial shares if they are financially literate. Investing accounts like Acorns is an investing service that allows young adults to put a low amount of money into partial shares.

Evy Polis was one of the students who starting investing for the first time in the pandemic, with more free time and spare change things became easier to navigate.

As a great number of Americans were stuck at home and adjusting their budgets, retail trading exploded, specifically in young Americans.

“Acorns has been huge in helping me navigate how to invest money during college, it’s cheap and it taught me how to start saving for retirement and explain stocks better,” Poulis, a graduate student at the University of Central Florida, said.

Polis also said investing should be a basic tool most college students should learn, so post graduation you are prepared to invest in full market shares.

Building a better future

Financial education also results in a better life outside of the classroom, according to the Finra Investor Education Foundation, which uses educational programs to assist Americans with financial assistance. Studies suggest that those who were educated in three states with mandated financial literacy had better credit scores than those who weren’t.

For instance, it’s been shown to reduce the likelihood of using payday loans among young adults and is positively correlated with asset accumulation by age 25.

Three years after a literacy-focused curriculum was implemented in Georgia, Idaho, and Texas, financial institutions saw a decrease in severe delinquency rates while credit scores rose.

Another study found that education increased the likelihood that college students would apply for financial aid and reduced private loan balances by about $1,300.

A day in the life

For some students, media literacy and civic engagement are some of the gaps in the American education system, but UGeorgia student Mikaela Cohen said financial literacy was the biggest gap of what should be taught to students when it comes to budgeting and saving. With extra time during the pandemic, Cohen realized the amount of debt she had racked up from studying abroad and knew it had to be paid off.

With some research from articles and family, Cohen started to keep a calendar for monthly expenses, set up autopay, and open an emergency savings account to take charge of organizing her finances.

With more free time during the pandemic, she was able to pay off her student loan debt, learn about different kinds of debt, open a high-yield savings account, and start investing in partial shares in Acorns after educating herself in personal finance.

Overall, Cohen said sticking to a structured schedule is what helped her get through managing her expenses.

“Whether it’s a diet or fitness plan, you have to do it every day or every other day, and get into a routine unless you’ll fall out of it, I think financial literacy and investing in the same way,” she said.

Parental loss was a tragic wakeup call

Other young Americans were forced to learn about finances due to the tragedy of losing a loved one during the pandemic.

Between 37,000 and 43,000 children in the United States lost at least one parent to COVID-19, an upsetting 20% increase in parental loss over a typical year, USC research shows. This forced many unprepared young adults to deal with their parents’ estates. Sudden deaths left young adults like Caitlin Moen and Mikaela Cohen in an unfamiliar world of wills and financial assets.

Moen, the Minnesota graduate student who learned to manage her late father’s estate this year, said, throughout the hardship, it was important to take care of yourself and give yourself credit for going through a financial crisis.

When Moen wasn’t scrambling, making phone calls or staring at her computer screen, she was finding ways to take care of her mental health as well. Paddleboarding and playing with her two dogs outside were one of the ways she took care of her sanity.

“I was outside the most I’ve been since I was a kid,” she said. “For mental health and sanity, I was like, I can’t be at a computer all the time, or on my phone all the time I need to be out.”

“It feels very isolating, but there are over 600,000 people who have died from COVID and have to deal with these things immediately,” she said.

Although Moen recognizes she wasn’t completely financially illiterate before her father died — her insurance company job offered some financial advice — saving and student loans were complicated and threw off her budget planning.

Then, Cohen’s father died during the pandemic. She had to find ways to stay organized and cope.

“I kept a calendar of monthly expenses for my apartment as well as my family’s house since my dad could no longer do it for my mom and brother,” she said.

The issue of being financially illiterate in America is not new, Pandit said. He wonders why the push for mandated coursework lags year over year..

Pandit also stressed the importance of practicing financial literacy every day, and learning is beneficial, but taking action and making mistakes will help you succeed most. He also said there should be more programs to exercise financial literacy throughout an entire lifetime, rather than learn it once and forget.

“After learning all the dos and don’ts about credit and debit cards, sometimes people will have to make mistakes,” he said.

“You can go to driving training, and take a test, but unless you drive you’re not going to remember you’re going to make mistakes, same is with financial literacy.”

Originally published in December 2021.