Stories from Ground Zero

Remembering 9/11/01, 20 Years Later

October 30, 2022

Through the accounts of first responders and those involved with building the 9/11 memorial, the accounts are intended to be heard and remembered throughout the test of time. With the purpose of highlighting each individual’s story, as well as preserving brevity, this piece is broken up into 4 parts. The index provided indicates the order of each individual’s story. Separating accounts are pictures from Ground Zero.

Index

- Kal Nassar – Former Detective Lieutenant at City of Yonkers Police Department, and SWAT team member.

- Robert Bock – Former Yonkers Police Department assigned to the Emergency Service Unit

- Rob Montalvo – Former Detective at Yonkers Police Department, Yonkers Emergency Service

- Rema Sayge – Former Senior Manager for Donor Relations & Stewardship at the 9/11 Memorial

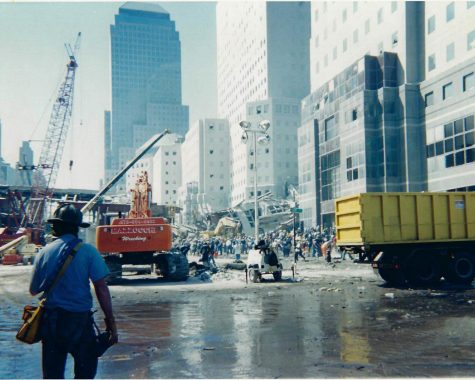

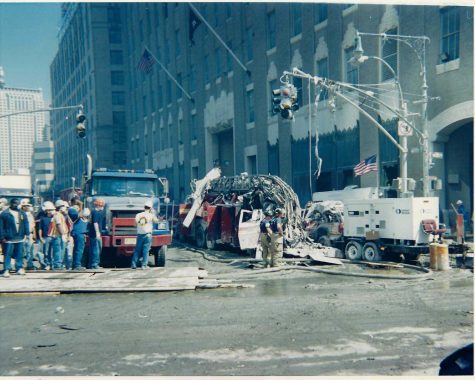

Manhattan, New York City, 9/11/2001. (Robert Bock)

Kal Nassar

“I couldn’t help but feel like there was something I needed to do to help.”

“I remember the morning of, I was sitting down with Jenna (Kal’s baby daughter) watching Barney at the time. Everything seemed like a normal morning.” says Nassar. “I got a call from another officer, asking me if I was watching TV, they told me to turn on the news immediately,” he recalled. When Nassar flipped the channel to the news, the second plane crashed into the tower, he said “I was unaware the first plane hit. It was shocking.”

Nassar wasted no time in his call to help. Nassar took his baby daughter to her mother’s house, then went to get himself prepared to get called down to help at the site of the attack. “The call from work eventually came around 11 AM. We were all called to the 1st Precinct, and from there, most of the unit went down to Ground Zero.”

“I was nervous but I knew that I had to go. I had no choice in the matter, I couldn’t help but feel like there was something I needed to do to help,” Nassar said, adding “and it felt very helpless when we got down there.” Nassar bravely helped in the best way possible.

Nassar, a long-time cornerstone of the Yonkers police department, serving more than 25 years in Yonkers across various roles, recalls that on the day of the attacks, they were not allowed to go on the pile since the fires were burning from the attacks. “Those fires were burning for months, but that initial day, we could not go on the pile because it was so hot. So we stayed and helped out with other things, such as buildings that needed to be evacuated. There were old- age homes down the block that we had to escort out of the area,” says Nassar.

It was not until the third day, September 13, 2001, after the attacks that first responders were allowed on top of the pile, Nassar says. “We spent all day on top of the pile moving rubble, trying to find people to rescue. After a while it became clear that it was no longer a rescue, but it was a recovery. It was tough, it was tough.”

Amid the chaos of the surreal morning, Nassar recalls the sights he saw vividly, to this day. “The damage to the buildings surrounding the tower was surreal. There were airplane parts in adjacent buildings, there was landing gear in the middle of the road. On top of the pile, you were able to see openings, 15 to 20 stories down, police cars, ambulances and firetrucks were all under the rubble when the buildings collapsed,” he said.

“Our purpose was to go down there and help. We tried our best. Some of our guys got sick and passed away from their illnesses. Lieutenant McLaughlin who worked with us passed away about two years ago from brain cancer that was attributed to the attacks,” said Nassar, adding“2,500 people died that day, but thousands more have since passed away, it’s tragic.” Nassar said he still lives with these horrific memories. “Do I still think about it every once in a while? Yeah, I do. Is it horrible to think about? Yeah but you can’t help it. Half of the stuff we saw is unspeakable.

When 9/11 happened the whole country came together to help each other, regardless of who you were.” he said. “I still fear attacks to this day, but I know there are people who work their hardest in order to ensure that it doesn’t happen again.”

Nassar was invited with a group of first responders to see the memorial before it was opened to the public. Recalling that memory was difficult. “I was not able to stay through the entire exhibit. I really did not want to see it all,” He said. “There were certain rooms with audio, people calling their families for the last time, it was so hard to hear, I couldn’t sit through that.” Nassar has not been back to the memorial since. Nassar says “I think that they did a beautiful job with Ground Zero. Everyone’s names are there, it is a prime area. They did the right thing, they memorialized what happened there. It is forever hallowed ground.”

And although the attacks are now two decades in the past, Nassar still has illnesses he deals with, as do many other first responders. “Once in a while, I get some breathing issues, the GERD (acid reflux). Many try to get me to go down to the city and get it checked out, but I have never actually had a full checkup done,” he said, “Do I wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares, once in a while, but a lot of the guys have had it a lot worse than me, that’s why I have tended to not be so concerned about it, I am thankful I did not suffer a lot of the ailments other guys have.” Nassar recognizes that there are the resources to help him at Mount Sinai hospital. “I know it is not wise of me to not seek help, but maybe one day I will do it,” he said.

Although 9/11 is now 20 years in the past, the memories and influence of the attacks still live on to this day. The sacrifices made by first responders like Nassar were essential in this country’s rebuilding and should forever be remembered. Amidst the chaos of the morning, selflessly, Nassar and other first responders were there for who needed them most.

Robert Bock

“We saw the first plane come wheezing down the Hudson right over our heads.”

Robert Bock was an officer assigned to the Emergency Service unit, working as a police officer for more than 33 years.

“I was at a friend’s house, heading to a meeting, about 10-15 blocks away from the World Trade Center. We were having a cup of coffee on his deck, mind you he lives on a hill, as we saw the first plane come wheezing down the Hudson right over our heads.” It was only a few minutes after that the first plane hit the tower, and millions saw the event on the news. “I looked at our friend and we were in shock, it was all of the sudden that the second plane hit. We knew something was up.” Bock headed home and prepared to be called with the rest of his unit down to the city.

“I knew as soon as I got the call to come in for work that it was going to be a tremendous disaster,” said Bock. Bock recalled that his emergency service unit had done some training in the past with Truck 3, which was the emergency service unit responsible for the city area. Bock says that they were being called in to assist Truck 3, but when both towers collapsed, everyone in Truck 3 was killed.

“We ended up responding to take their place. The training we did was never designed for that,” said Bock.

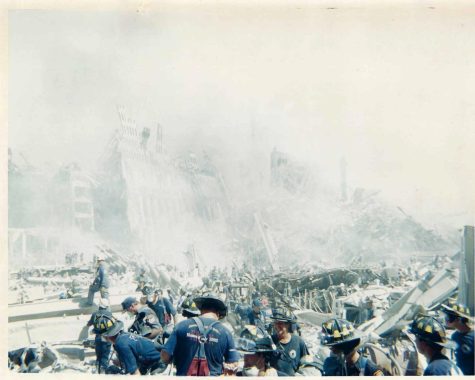

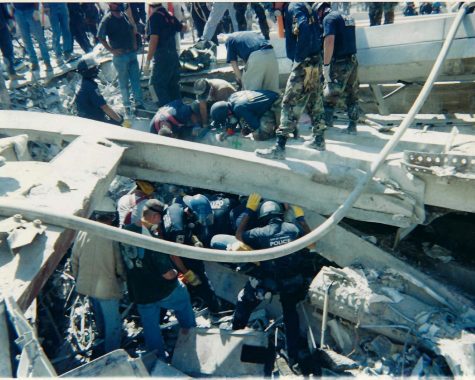

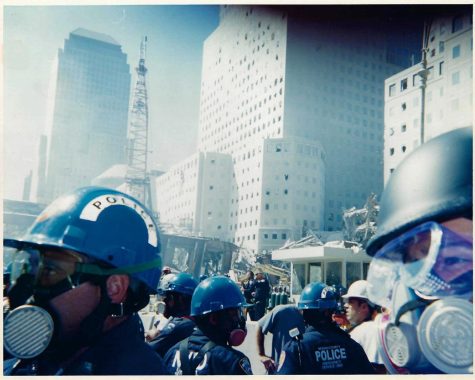

(Robert Bock)

When he arrived “there was so much mass confusion and downtime,” Bock said. He does not attribute that to any sort of lack of leadership, but more so to the unexpected and unprecedented nature of the situation. “The repeaters for our radios went out, they were actually mounted on the World Trade Center. The repeaters get the sound around the city as they magnify the sound. They were placed on the World Trade Center because they were the highest buildings. When they collapsed it knocked out our communications.”

The radios were not able to contact those who were far away but only those who were in an immediate radius. Bock said that this confusion made coordination difficult, but recognized that the first responders did an amazing job battling that adversity. “Multiple agencies were not able to talk to each other, the glitch in mass communication was a battle, but the issue has since been fixed.”.

Amid the chaos of technological glitches amidst the attacks, there were more difficulties for first responders to navigate. Shortly after the attacks, engineers arrived at the surrounding city blocks and set up lasers on many buildings.

“The lasers triangulate, sensing where every building is. There were lasers on each building, and one laser sensed that a building shifted,” Bock said. He recalls hearing an alarm while working on top of the pile and looking for his partner so they could safely leave the area as the building around them was collapsing.

“The alarm was going off, and my partner was down a little but in the rubble among the caves and caverns. Next thing we knew the building was collapsing and I was yelling at him, ‘Let’s Go! Let’s Go!’ We had to haul up out of there.” Bock remembers the feelings of panic but said “obviously I was not going to leave him, he is my best friend and my partner, I was not leaving him. I remember everyone was getting out and the building was collapsing. I was thinking ‘We are going to die right here and now,’ ” adding “the buildings were coming down, so we were looking for a place to jump into, in between the buildings and rubble to run to and hope for the best… luckily fear makes you run quick, and we were able to get through this tunnel created by a building. It was the only way in and out, for over 1,000 people, if that building were to collapse, it was likely that there would be another 1,000 casualties.”

Bock says that he remembers the feeling of despair but said “If I am going down, I am going down with my partner.” Bock is thankful for getting out of there in time, Bock was the only person who waited for his partner.

Bock recalls additional confusion in the morning of the attacks before even arriving at the sight. “Initially it was thought that the airline just crashed into the tower, a lot of different things were coming in . . . ” When the second one hit, we heard that it could have been a missile. We did not know what was going on because there was no communication.” Bock said it was not until he heard that the Pentagon was hit that he heard that America was under attack from another country. “Luckily for some reason, I was able to communicate with my wife who was back at home, and she was telling us all what she saw on the TV as developments were happening.”

Bock recalls his emotions leaving the house the morning of the attacks. “My son was two years old, and my wife was pregnant. They were on my mind. We have a big family, so I told my family to grab as many canned foods as possible. We had no idea what was going to happen, we were under the impression that the country was under attack from another world power.” said Bock. There were many stories circulating, and Bock recalls that once he got to the site of the attacks, there was no way of verifying anything that was going on due to the lack of communication services.

On 9/11/2001, Bock headed down to the World Trade Center around noon and stayed until around 2 am. “When we went down there the first time, we were unprepared, we did not have proper masks. We had the blue masks that we currently use, as we carried them in case we were in contact with a dead body. With the amount of debris and dust and everything else that was down there.” Bock added “we were at the point that we were going through them so much and there was a point that we were wearing the same ones for hours. The masks started off blue, and would change to become brown.”

It was not until the next day. Bock said that they were grabbing masks from Home Depot that were used by sheetrock workers. Bock recognizes that those masks were not able to prevent all the toxins that were in the air. “Those masks could not stop what we were breathing. You have to remember, we were breathing jet fuel, building materials, organic materials like rugs and computers and pulverized humans.” Bock says that because of his experience, he suffers from about four to five certified illnesses from the attacks. He takes 9 different medications a day and sometimes uses a respirator to treat his ailments.

Bock says that the process of treating his illnesses has changed over time. “Originally, when everything first started, we were appointed to our local hospitals for about the first year. Mount Sinai was developing its program for first responders at the time… now Mount Sinai deals with us and our personal doctors exclusively. It is much more organized, and it is extensively advanced. They will do it all for us, they give us only the best.”

Bock appreciates the organization of Mount Sinai and what their program has become but says “there were many who passed away that were not able to seek proper treatment before they passed away. There was a blip for 3 to 5 years that the hospital was turning those away that did not see treatment within a certain time frame, but then they realized that the illnesses from the attack were developing. People were getting cancers of all kinds that were developing over a span of time.”

Bock mentioned the passing of others involved down at Ground Zero, “Jimmy McCabe died of throat cancer because of 9/11. A young man named McClaughlin died of brain cancer. Both those incidents were diagnosed after the 5-year mark. Many were dying, and it took some time for the hospital to realize that the illnesses of first responders were continuous . . . New lists of illnesses come out every day of illnesses attributed to 9/11. Mount Sinai realizes that now, and they are treating those seeking treatment the right way.” Bock said.

Bock emphasized that there are only three times in American history that more than 3,000 Americans were killed in one day, saying “There was no plan for this.”

Bock says “I have not been down to the city since then, I have not been back and I won’t go back. It is a bad memory.” Bock says that if he ever decided to go back, he will only go with those who he was there with. “On top of the rubble I remember my boots sliding from how hot the ground was under me, we had the fire department spray our legs to cool them down. In our rescue mission we saw limbs, torsos and bodies that were without clothes, as they were completely burned off and pulverized. I remember looking down and asking myself, ‘where did all the desks and computers go?’… The memories to this day are still vivid as ever,” he said.

Bock added that “I try to suppress and not think about many of the memories, but when you talk about those moments it comes back to you. You cannot dwell on that shit, because it will eat you up, it will make you insane. But people ask, would I do it again, would I go down there again? I say I wouldn’t but I know that if I was presented with that situation again, I would 100% be back down there with the guys I was with, even knowing the repercussions.” The quality of the character of Bock and many other first responders is what drove them to help others, and sacrifice their own health and safety. It is those people that we should remember and be thankful for amidst the horrible memories of the attacks.

Rob Montalvo

“I was spending my 36th birthday digging for people, it was just so overwhelming.”

“I was home because I had worked until 1 AM the previous night. I got a phone call from my partner around 8:30 AM asking me if I saw what was going on in the city. I turned on the news, and we thought it was a small plane, and we were not sure what it was. Shortly after we got a phone call from work telling us that ‘We are not sure what is going on, but please be prepared in case we have to do a rapid response.’ I stayed on the phone with my partner for a while, and I saw the second plane hit. At that moment I knew that this was not going to be good and that it was not an accident. Shortly thereafter we got the call to come in,” says Rob Montalvo, former Yonkers Emergency Service member involved with the Special Operations Division (known as SOD).

On the way down to the city Montalvo recalls the eeriness of the morning, saying “just the silence, there were no cars, there was no noise. We were loaded into these cars called Deuce and a half’s with 15 to 20 of us in each, with our tools. But still there was just silence.” Once Montalvo arrived in the city he saw people walking away from the sight of the attacks. He recalls the moment saying “We can see the smoke off in the distance and for as long as we could see there were people walking away from the sight very quietly. It was unnerving because we did not know what we were going into.” Fear in the form of silence was very real for Montalvo recalled.

“When we first got to Ground Zero, they were trying to get people to the site itself to evacuate the surrounding buildings. I was assigned to evacuate a senior citizen’s home that was a block and a half from Ground Zero, they were going to be taken on buses back to Yonkers,” Montalvo said.

“As we were just finishing up, we heard that Tower 7 was going to collapse. In the process of just finishing evacuating the people, that building came down. It sounded like a freight train as the floors fell on themselves. It was one of the scariest things I have ever been involved with,” he said. Montalvo recalls the visions of the event saying “the plume of smoke chased us down the street, we were running trying to take cover, and we found a cubby hole. The clear day turned into night.” Montalvo says that he could not envision what it must have been like when Towers 1 and 2 collapsed.

Montalvo wanted to make sure that he was helping people but he says “we did not know what was going on, there was so much information coming at us and we were all trying to help ourselves and each other. We still did not know what was going on, we had no communication back to our families.” Montalvo said “It was very tense, we were not sure if there were more planes coming for New York.”

In the days after, Montalvo was still assigned to help at Ground Zero. He spent the first two days there and was assigned a day off before being placed on 12-hour tours followed by a day off and another 12-hour tour on the pile. Following that, officers were assigned to work 2-hour tours on their normal jobs. “That schedule lasted until about the third week of October. I went down on the 11th, I stayed until the 12th, and after that I went once a week for about three to four weeks,” he said.

“The thing that sticks with me personally is that my birthday is September 12th. I remember spending my 36th birthday, on the pile digging, and I was just thinking to myself ‘please let me find something or somebody as a birthday present.’ I was spending my 36th birthday digging for people, it was just so overwhelming,” Montalvo recalled.

He says that he and other first responders talk frequently and ask “where did everything go, the phones, the filing cabinets, the desks because everything was just basically dust? We did what we had to do, but when we had time to really reflect, we were just taken back over the fact that when you think about it, we did not see any of those things, everything just turned into dust.”

Montalvo said that in his nearly 30 years in the police department that never in his time “did I feel so close and appreciated by people.” Montalvo says that the community in America in the 6 to 8 months after was outstanding, saying “everyone came together, it showed how powerful this country could be when it comes together as we did. It took something so terrible for all of us to come together.” Montalvo says four years after the attack, he became a detective, saying “I wanted to be able to investigate and get to the problems that led to the attacks. I think about some of the things that slipped through the cracks and I felt like maybe if I can make a difference and investigate this and maybe if I followed up on these things in a different capacity outside of the patrol capacity I could make a difference. I wanted to put in my share to make sure that this never happened again.” Montalvo was a detective for the next 14 years of his career.

Montalvo spoke of his life at the time of the attacks, saying “My wife was pregnant with my daughter who was born in December of that year. My outlook was totally different as to what was going on, but it scared me since I did not know what I was getting into once I was down there.” Montalvo mentions the lack of connection to communication services, as he emphasized that because of those difficulties he was not only not able to check in with his family to make sure that they were okay, but he was not able to stay informed on what was going on in the world in regard to the other attacks. “Everyone had their family on their mind, it was pretty God damn scary.” Montalvo said. He recalls staying overnight in the city from the 11th to the 12th, while he was going back and forth making sure equipment was brought to appropriate places. “I was assigned to a team nicknamed the ‘chain gain’ and we were digging, moving the piles . . . There was no time to be tired. . . “When you first went down there we were in shock, we had no idea what was going on, so we had to do things fast just in case things were to go south again.” He recalls hearing the horns going off, indicating buildings were about to collapse. “When you heard those horns it was as if you were running for your life because you did not know what was going to happen. When you hear those horns you drop everything and you run for cover, it happens quite a few times, it scares the shit out of you.”

Every time 9/11 comes around Montalvo and the group of people he was there with look to find time to reflect on their memories and speak with one another. “It seems as though every time we sit down and speak, we kind of remember a little something, or someone mentions a little something and the memories come back” he continues to say “although we are now all retired. That is likely the largest event that many of us will ever be involved with.”

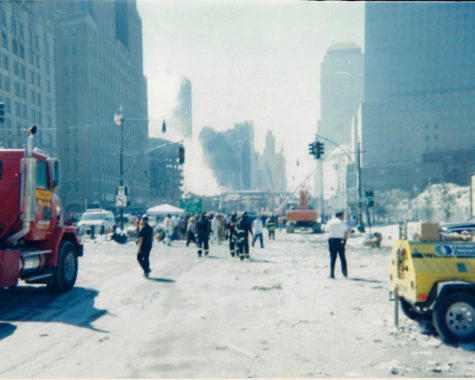

(Robert Bock)

When Montalvo was asked of his experience visiting the city, 20 years after the attacks he said “I have not been back since then. I tried going back when they invited me to the museum opening but I just could not go.” Montalvo mentioned a training that he and a former partner were assigned to attend, he said “the training was only three city blocks away from Ground Zero. I said to myself ‘one day after training I will go over there with him and see how I do’,” adding “I was able to walk about a block and a half, I started shaking, I could not bring myself to go over there. To this day I have not been back. I get full of emotion and this … very tense feeling. Even when I drive on the West Side Highway, I still get that feeling.” Montalvo says that if he ever goes back it will be with the group of men who he was with when he initially went down there.

Montalvo voiced that he ensured to educate his daughter on the details he remembers from the attacks. He said “I had her watch news footage and I showed her pictures and I sat down and discussed everything with her. She has a very good first account of what went down and how it went down.” Through his daughter, Montalvo looked to have his account of the event live on, and he is very proud of how she had done so, he says “in an eighth-grade project, she did an amazing job telling the story, her teacher and class loved it.” Montalvo says the reason he took the time to share his account with his daughter is because she mentioned how briefly the attacks were discussed in her school’s curriculum. Montalvo emphasized the importance of sharing these accounts with younger generations so the stories of first responders never get lost.

Looking back on the attacks is anything but easy for first responders. Montalvo says he is blessed in the fact he has not suffered any physical ailments from the attacks, but he acknowledges the reality of the psychological effects of the attacks. “It is always the week of and the week before the attacks that I get this eerie feeling.” He adds, “I have to say my birthday is not the same, I do not enjoy it as much as I used to. I prefer it to be a quiet day of reflection, the event changed the world and it changed my life.” Montalvo says that despite the attacks being two decades ago he “feels like he is there” when the week of the anniversary comes around.

(Robert Bock)

(Robert Bock)

Rema Sayge

“From the second I walked in the doors of the museum I was moved every single time, every single day.”

The stories of 9/11 go far beyond the accounts of first responders; everyone has a special recollection of the event. Rema Sayge was the Senior Manager for Donor Relations at the 9/11 memorial. Sayge remembers finishing a major production of a TV show in New York in the days prior to the attacks. She brought friends with her for a getaway and recalls how she found out about the attacks. “I was sleeping when people were calling me, they thought I was still in the city. My friend and I woke up and turned on the news. We were glued to the TV, trying to figure out what was going on.” Like many others around the world, Sayge was in a state of shock and awe, looking for answers.

Sayge has been involved in the entertainment business all her life. When she began her involvement with the 9/11 Memorial she was the director of operations and visitor services. “My role was to hire many people, then train, mentor and motivate them so that the memorial was staffed and ready to go.

When I started there I actually did not want the job, I resisted it, but I felt as though I was contributing to someone larger than myself, and that is what prompted me to take the role. It is very parallel to what I do in terms of bringing teams together to usher in millions of visitors from around the world. I work on a lot of projects that are on the world stage and this is one of them,” She said. Sayge worked at the Memorial for 7 years, and she is currently a program producer for Empire Entertainment, as she continues to launch major projects, creating unique cultural and entertainment experiences.

Sayge says that she tried leaving the job three times, but she was drawn back by the growing attraction that the memorial was becoming. “The memorial was seeing record attendance year after year; we became the number one sight to visit in the country. One World Trade was being built, what I needed to do was not complete. I felt as though what I was doing had a need, so I did not want to leave.”

Sayge says that the construction of the memorial began in 2006, when there was a nationwide contest that allowed people to submit designs. Michael Arad won that contest to be the architect for the pool. He was selected by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) who was led by Chairman John C. Whitehead. Whitehead in conjunction with LMDC filtered through all the contests submissions and chose Arad’s design. Sayge recognizes the various components that went into the construction of the memorial and the museum. The design for the Memorial and Museum were completed in 2006.

(Rema Sayge)

“When I started with the museum in 2010 there was still a hole in the ground,” said Sayge, adding “It was on the 10th anniversary of 9/11 that the Memorial opened up, and it was in March 2014 that the Museum was made open to the public.” After eight years of construction the museum was complete, despite a major hurricane in 2012. The memorial alone saw more than 1 million visitors in the first year that it was open. Sayge says that “private underground tours of the Museum were given to select high level people, including world leaders, heads of state, kings and queens, celebrities, you name it.”

Although Sayge takes great pride in the phenomenal job that was done memorializing the event, she shares emotions with many of the first responders who get emotional when visiting the memorial, and understands why some may not want to come. “Every single day I felt those emotions. I would start my days off normally getting my coffee and getting on the subway to head to work, and once I stepped foot on the memorial, I was always reminded,” she said. “Every day was a new day. There were always new people surrounding it. There were various ceremonies that were celebrated every day such as celebrating people who’ve died, birthdays, with white flowers, or whoever’s name was getting added to the memorial.” Sayge said that personal connection and emotional investment certainly developed as the years went on, saying “you get to know certain family members, and you begin to get moved by all these stories. I met a lot of people.”

Sayge referenced how much she learned daily from the relationships she created, saying “From the second I walked in the doors of the museum I was moved every single time, every single day.” But the experience was just too much for her. “That was one of the reasons I chose to leave. It took a toll on me and my mental health. I work in the film business, event business and entertainment business. On a higher note, I needed to escape the death aspect of things. Every day I went to work 70 feet underground and it had a mental and physical toll on me. It was time for me to go, although it took two years for me to leave.” Sayge said that not every day was filled with tears and sadness, as there were many good times in her experience.

When asked about how she feels in regard to many first responders and New Yorkers not visiting the site, Sayge referenced a project launched with work before she left called Our City, My Story. “We realized many New Yorkers were not coming to the museum or memorial, and we were trying to encourage people to come and get the experience.” She recognizes the emotions of the first responders who have not visited the museum.“I respect and understand their position, with PTSD it is very traumatizing and I totally empathize with them and I understand that.”

Sayge says that the ground the museum and memorial on is sacred. “There is DNA in the rubble and land, people died right there. The ground that you walk on when you go down there is top priority to be treated the right way. They always knew right away that things like a shopping center would never go there.” Sayge said “the memorial and museum are there to serve as a reminder to remember the event. It is there to tell stories for those who can no longer do so themselves. I am so proud of the development of the area. It took lots of hard work, but the project is certainly something we are all proud of.”

Through the past 20 years, we have sat reflecting on the events, in heartbreak. Through beautiful memorials, the lives of those lost will never be forgotten, but it is of the utmost importance that the stories of first responders are heard. As real as the attacks of 9/11 were, there are many young people who do not understand the reality of the event. It is through these personal stories that the community shall remember the attacks nearly 20 years later, and it is through the accounts of those who lived through the events that show why America will never forget 9/11/2001.

Sharon • Jan 16, 2023 at 11:33 am

After the terrorist attacks, we as Americans, promised we will never forget but, sadly, we had. History had been purposely distorted and our heros were left behind. Many of them perished in a horrifying way that day but, so many others had to live their lives battling a new evil. It’s undeniable, the ones that we call 9/11 heroes were affected mentally and physically and sadly, Americans forgot about them and their struggles, from cancer to PTSD and everything in between. What can we do as a society to support them and make them feel appreciated? I think a good start will be saying their names. I was blessed enough to get to know and love one of them, shown in these pics. He was my hero and now is my Angel.

I love you James Murphy, you will always be in my heart, until we see each other in Heaven ❤