The Romance of Wooden Boats

By Keating Zelenke

October 24, 2022

On the counters and tables inside the Frank M. Penney boat shop in Sayville, screwdrivers and rubber mallets marinate under a thin layer of sawdust in repurposed Chobani yogurt containers and old coffee tins. The smell of wooden spruce planks makes a cozy building feel cozier, and the iron wood-burning stove at the heart of the main room makes the place cozier still.

Sitting in a circle of chairs around the stove is a group of retired men who look just as you might expect them to: caulk-stained t-shirts, worn-in hats, dusty crew-neck sweatshirts. They are museum exhibit mannequins come to life.

I knock on the door softly. On the other side, the rusted iron latch clunks heavily. “Welcome,” Joe Pecoraro says jovially as he opens the ancient wooden door. “We build boats here.”

His hair is slightly curled from the sea air, the cuffs of his sleeves stained brown with varnish. He’s got the trademark Long Island accent and he’s nursing a paper cup of coffee. Immediately, Pecoraro leads me over to the dismantled 14-foot boat that occupies close to half of the main room.

“We’re restoring this hundred-year-old Shore Bird,” he says, guiding me onto a step stool so I can get a better look inside. “There’s only two in existence.”

The skeleton of the boat is made up of wooden beams, about an inch or so thick, that curve upwards from a thin slit at the bottom only a couple of inches thick. I feel like I’m standing over the ribcage of a fish twice my size.

“A retractable keel goes in here,” he says unprompted, running a calloused hand along the slit at the bottom. “On the South Bay — the Great South Bay — the water’s shallow.” He explains that by raising the keel, sailors could come in closer to shore at night.

Pecoraro is one of the volunteers at the Penney boat shop, a century-old building that now sits across from the Long Island Maritime Museum in Sayville. The shop has been the second home of several volunteer craftsmen for more than 25 years. Pecoraro himself has been building boats there for well over a decade. Tom Whitehurst, another retired guy with a white beard and a faded Oneonta hat, started at the boat shop around the same time as Pecoraro. Both of them urge Martin Sievers, a legendary Long Island boat builder, to talk with me.

“He’s actually taught a few boat-building classes, wooden boat building,” Whitehurst says with a thumb jutting over at Sievers, in a gray fleece jacket.

“Marty’ll give you something for your thesis,” Pecoraro says. “Tell her a story, Marty.” “What do you wanna know?” Sievers asks me from across the open-faced skeleton of the Shore Bird between us.

I ask about his favorite boat he’s ever built.

“The catboat,” he says like it’s obvious.

“The Gene K?” Pecoraro asks.

“The Gene K.”

Whitehurst guides me over, and hanging on the wall right when you walk in, there it is. A picture of the three of them — Whitehurst, Pecoraro and Sievers — all sitting on the top edge of

a beautiful catboat they finished in 2003. The hull is creamy white, and the top has a glossy wooden finish. It was displayed on the front lawn of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. for a special exhibit on American shipbuilding several years ago.

Many of the boats they restore — including the Shore Bird sitting off to the side — will never see the water again. The group works on these older boats so they can be preserved in the Small Craft Building across the lawn of the museum’s campus. The Gene K, however, was built from scratch and designed to sail. In the photo, it glides across mild waves in the bay. Whitehurst points out the Islip courthouse in the background.

“I’m showing them how to sail,” he says, pointing to himself with notably more hair. In the photo, Sievers, dressed in a bright yellow vest, seems to be at least half listening to Whitehurst’s lesson. Pecoraro, on the other hand, is leaning back like he’s about to fall in the water.

However old-fashioned wooden boats may seem, they are the lifeblood of the communities on Long Island’s South Shore. Even before New York City became the largest port on the East Coast in the 1800’s, boats shaped life on the island.

On the marshy banks of the Patchogue River, one man in particular — Gilbert Monroe Smith — drastically impacted the shape and style of boats on the bay. He built more than 400 catboats for baymen and fishermen during a 66-year career, adapting his boats for strong, unpredictable winds and shallow, sandy sea floors — common conditions on the Great South Bay. The independent baymen of the late 1800s and early 1900s bought these Gil Smith cats for catching oysters, for fishing, and even occasionally for racing.

Big oyster companies, wanting to collect as many shellfish as possible, used larger boats that dredged up shells along the seafloor. As the boats scooped up oysters, they rode up a conveyor belt right into the gloved hands of workers, who’d bring them to culling houses to be shucked, and then sailed by the boatload into New York City to sell. One of these mechanical dredges — built in 1929 — is docked outside the Frank M. Penney boatshop, waiting for the volunteers to renovate it.

Smaller row boats, called Sharpies, could also be used for recreational oystering and sailing, or to tend these larger crafts. Sold for only $20 in the early 1900s, they were the most common ships on the bay.

And Long Island has its own set of winter craft, too. When people further up the Hudson started sailing ice boats for sport, the U.S. Life Saving Service — a precursor to the Coast Guard — saw an opportunity to innovate. Ice boats and ice scooters couldn’t be used for sport on Long Island — salt water doesn’t freeze evenly like freshwater does — but maybe they could be adapted to at least get across the bay to Fire Island during the winter, when shipwrecks are most common.

The history of shipbuilding on Long Island is filled with these tweaks and small innovations. Maybe they are all evidence of the instinct felt by many of those who have found a home on the South Shore: to adapt and to stay.

But the evidence and history of some of the earliest settlers on Long Island is steadily becoming harder and harder to find — and the history of Indigenous people before those settlers is harder still.

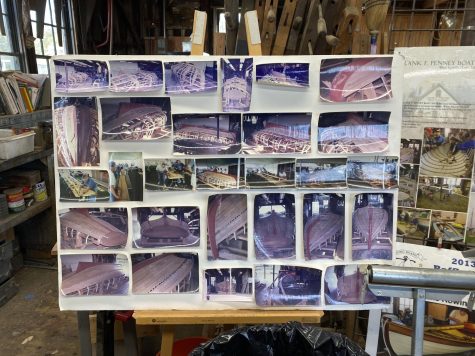

“Are you at all worried about these traditions being lost?” I asked Whitehurst while he showed me a series of pictures of the construction of the Gene K.

“Well, that’s why we’re doing this,” he replied. “They’ve been doing this for 30 years here, and I’m a new guy, and I’ve been here for what, 12 years?”

Inside the boat shop, volunteers use the same tools and techniques that a ship-builder would have in the 19th century. The walls are lined with the same stencils that these craftsmen used, and on hooks in cabinets and underneath shelves are the same hand tools.

Despite the clutter of tools hanging from the ceiling and wood stacked against the walls, something feels oddly minimalist about the place. And then it occurs to me — there are hardly any wires. The only electrical equipment the volunteers use are bandsaws to cut larger pieces of wood — and the lights, if those count. All the boats are wooden, and many are so old, they are among the last-existing boats of their models, like the Shore Bird.

Museum guides give tours on the Priscilla, an oyster sloop the volunteers renovated in 2002. Originally built in 1888, it is the oldest surviving boat of the Great South Bay’s oyster fleet — and one of the only survivors at that.

Pecoraro explains to me from the second floor of the shop how they work on large boats like the Priscilla, which is sixty-feet across. I listen and wander around the room, looking at the walls of rope, repurposed Nesquik cans full of screws and nails. There’s an old depth recorder on the wall, covered in a layer of sawdust. Light only comes in from two windows — one overlooking the building where they used to work on boats, and one overlooking the dock in front, where the Margaret is floating, and a private yacht is temporarily docked.

One of the comforts to be found in the Frank M. Penney boat shop is in its stillness. Surrounded by tools older than I am and used at first by people who are long dead, there is the gentle reminder that sometimes things change, and sometimes they don’t. Both stagnancy and progress can be frustrating and scary, but both can also be good.

On the second floor, the hollow sound of my shoes on the old wooden floor fills the ears as Whitehurst and Pecoraro fall silent. Pecoraro is investigating an old, heavy-duty sewing machine in the corner that was once used to make sails — the leather seats on his car are coming apart and he needs something to fix them. Whitehurst is looking around for something else “interesting.” When it seems like our conversation has ended, I wander over to the stairs to go back down to the main floor.

“This is a knee from a ship, where the bottom of the boat and the side of the boat join,” Whitehurst says from behind me. I pause and turn back to look.

Between the wall and the ceiling near where he’s standing, there is an old, rotting piece of wood, riddled with holes and shaped like an upside-down L. I initially thought it was just a support for the ceiling, but now I see it is simply nailed on the wall, like an embellishment or decoration. Whitehurst swoops an arm up along the shape in a high arc.

“The interesting thing is they used to go out in the woods and look for certain trees … and they would cut this with the natural root because the wood naturally curves here, and it makes it super strong,” he says.

I look at the root for a long time and I think about the craftsmen who — decades ago — pulled it from the ground and nailed it to the side of a boat, which I assume is now long gone. And I think about the craftsmen in front of me who saved it and hung it on the wall like a hunter hangs a deer’s head. Something tells me that as long as these guys are around, no one has to worry about traditions being lost.