‘I don’t understand them.’

These English Language Learners in New York need a more equitable education.

September 6, 2022

James is like most eighth-grade students. On a typical afternoon, he does his homework, watches TV and gets ready for school the next day. The 13-year-old wants to save people and become a doctor one day, but he knows he has to get good grades and go to college first.

For most students in the United States, the path from K-12 education to higher education or joining the workforce is fairly simple. For English Language Learning students like James, the journey can require a steeper hike.

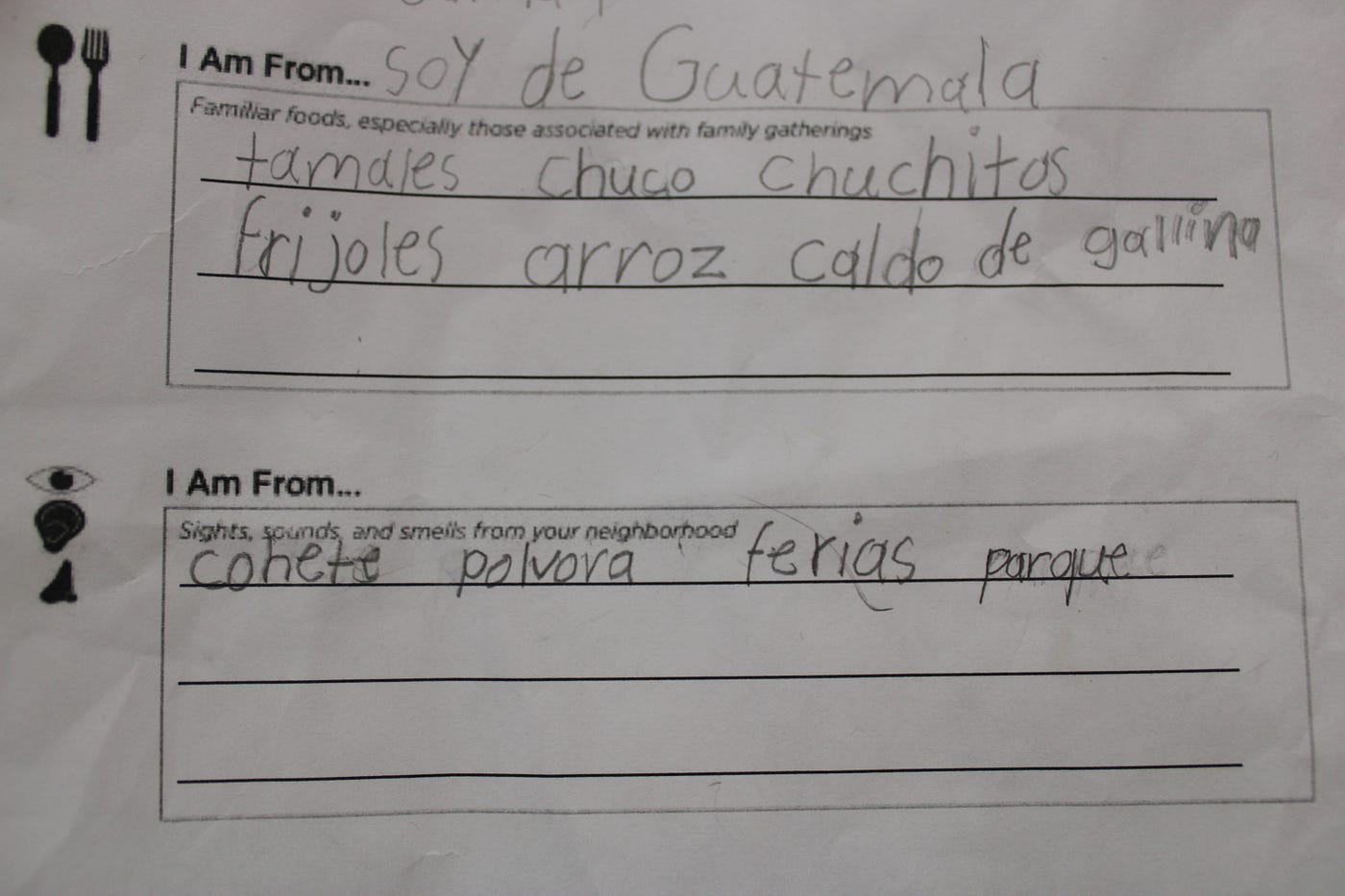

James, which is a pseudonym to protect the minor’s identity, emigrated from Guatemala to New York just two years ago. Now, he attends Kakiat STEAM Academy in the East Ramapo Central School District where he has been identified as an English Language Learner (ELL).

Primarily speaking Spanish and navigating through a new country that is predominantly English-speaking, James said that he sometimes feels like giving up.

“When they all speak English, I don’t understand them,” James said through an interpreter. In school, his class frustrates him.

“I try to read or listen to know what they are saying.”

His experience is not uncommon in the East Ramapo Central School District in Rockland County, New York, where ELLs made up 16% of the public school student population as of August 2020.

According to data from the New York State Education Department, Rockland’s ELL public school students graduate at a rate of 33%. The state average of 86% reflects the reality that ELL students have a disproportionate graduation rate.

Of the 2,952 graduates from Rockland County’s 10 public high schools in 2020, only 4.5% were ELL students. These students perform at a considerably lower rate than that of their native English-speaking peers.

Various factors including inequitable resources and socioeconomic status contribute to the lower-quality education some students receive, according to the Brookings Institution, leaving more than half of ELL students in the county without a high school diploma.

In 2015, the state released a set of principles under the “Blueprint for English Language Learner/Multilingual Learner Success.” This document was distributed to teachers and administrators across the state in an attempt to ensure that all students “attain the highest level of academic success and language proficiency.”

Outlined are specific content and learning objectives to provide students with opportunities to comprehend learning materials in both English and their home language.

A state report in 2019 revealed that the blueprint “resulted in modest improvements in student achievement and graduation rates combined with a decline in the dropout rate.”

While this report bodes well for New Yorkers as a whole, the state education department acknowledged that in Rockland County, the dropout rate of ELL students grew from 33% in 2019 to 46% in 2020.

“The dropout rate is relatively high in certain areas because [the students] are supporting their families,” Denise Hannoui, director of TESOL Field Experience & Clinical Supervision at Stony Brook University, said.

The East Ramapo Central School District is one of these areas. With 92% of East Ramapo’s ELL students labeled as “economically disadvantaged” in 2020, some students have to prioritize familial obligations and finances over their education.

Nadia Williams, who teaches English as a New Language (ENL) to 125 students at East Ramapo High School, said she has a great deal of experience with students who fail or drop out of school because they struggle to balance work and school.

Williams said most of the English Language Learners in the district come from the Caribbean and Central American countries including Haiti, Nicaragua and Guatemala. When the students arrive in the United States without their parents, as unaccompanied minors, they are often released from detention centers to distant family members and friends.

In Rockland County, 645 unaccompanied minors have been released to sponsors as of June 2021. Before the apprehended children are placed with family members or sponsors, they are in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is required to provide educational services, food, shelter and medical care until a suitable environment is established.

“There are many unaccompanied minors here by themselves,” Williams said. “They have to pay for their rooms. They have to pay for their food. They have to find work, and they come home at 3 o’clock in the morning.”

Williams often allows these students to take naps during class, knowing that they will not be able to focus on the class materials most days after working long hours.

“They have to work. For those students, it’s not like they have a choice. I see with students that drop out, they’ll come [to school] until they can’t,” Williams said. “It just comes to a point where they’re either not allowed or it becomes too much. They have to send money back to their country.”

As students are disadvantaged by their socioeconomic status and limited access to personal educational resources, East Ramapo schools lack the financial resources to provide ELL students with materials that would benefit them in the classroom, according to a district financial audit.

An annual report for the 2019–2020 school year showed that the per-pupil expenditure in East Ramapo schools is less than that of other public school students in Rockland County. The lack of money available to these schools may account for the minimal resources provided for ELLs and other students in the district.

While the ELL programs in East Ramapo schools meet the requirements of the state education department’s regulations, which “monitor and support the student’s language development and academic progress,” additional funding would undoubtedly play a large role in supporting ELL students facing their unique challenges, Williams said.

“If we did have additional resources for students, I believe that we would probably be where we want to be a little faster, and in a more proficient, easier and better way,” she said.

The Nyack Union Free School District in Rockland County — about 20 minutes from East Ramapo — has an above-average per-pupil expenditure for students in the district. Here, 52% of ELLs graduate from high school while only 26% of these students graduate from East Ramapo schools.

The financial disparities between these districts may account for the varying availability of resources that benefit ELL students.

In Nyack schools, the ENL program includes Transitional Bilingual Education for children in kindergarten through second grade, as well as the ENL program that is offered for all grade levels. Enrichment and summer programs that provide additional assistance with homework, study skills, and academic and linguistic support are also made available for students.

Unfortunately, ELL students in East Ramapo schools do not have access to similar programs — due to a lack of resources.

Though students were recently provided with new laptops to complete their schoolwork amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Williams said technology is “just one piece of the resources that students need.”

“We bought computers and we bought cases for them, so at least you had a computer and a case, but there are other resources that a district like Nyack has,” Williams said. “Additional resources like the right kind of textbook or the ‘right kind’ of curriculum, per say, for ENL students… We don’t have money to buy what we need.”

To compensate for the lack of resources for students, educators in East Ramapo are often left to use their discretion and buy materials for their classrooms with their own money.

Without a significant increase in the budgets or quality of resources for schools in East Ramapo and the rest of Rockland County, English Language Learners are at a disadvantage.

Building more equity within the school systems in both Rockland County and the rest of New York should be implemented as the circumstances that ELL students are faced with are not typical of an average, American high school experience.

“They know their experience is different,” Nyack High School ENL English teacher Carmellina Cafferalli-Hains said. “There’s a lot of stress and a lot of pressure on them to survive… They’ve got a lot of ‘adult’ responsibility before your [general education], typical student has.”

An educator for 36 years, Caffarelli-Hains acknowledged the challenges faced by ELL students that range from learning English grammar to working to pay rent. Her belief in her students and hopefulness mirrors the sentiments expressed by Williams who praises the students that persevere through extremely difficult situations.

Though saddened by the number of ELLs who are unable to graduate from high school in four years like their native English-speaking peers, Williams said, “What we admire the most about our students is the resiliency that the students come with.”

“Their repertoire, their experiences, having to walk across the border to go to a detention camp and then come [to Rockland], sets a lot of them up for success,” she continued. “And the resiliency we see is not just with one or two students. Enough students come and in 4+ years, graduate from an American high school.”

“Hopeful for the future of her students and proud of her work, Williams said, “We might not have all the affluence wealthier districts have but we’re still sending students to university and giving them the support they need to succeed.”

Originally published in December 2021.