One of the rooms in Rashana Bajracharya’s apartment in Kathmandu seems to function half as a gym and half as an art studio, as paint tubes are clipped to a wooden furniture behind a treadmill. Her apron hangs on one of her many easels. Her brushes sit on a yellow pot on a small corner table. Her wooden bowls are covered in dry paint.

Despite being nearly full with her paintings, the small room doesn’t even come close to fitting all of them. Various pieces are spread across the apartment, decorating its walls alongside photos of her wedding. Others have been sold to collectors or are on view elsewhere.

Sitting on the brown couch of her living room, Bajracharya scrolls through her iPad, looking for one of her most recent pieces: Lakshmi Narayan. Painted in 2023, the work portrays the Buddhist deities Lakshmi and Narayan in an original manner. In their most traditional representations, Lakshmi is massaging Narayan’s feet, but, in Bajracharya’s version, it is him who is massaging her feet.

Meticulously detailed, the painting strives for perfection. The deities are standing over a turbulent sea, but there are no signs of panic on their faces. Lakshmi is sitting on a snake-shaped throne with her eyes closed, relaxed as her feet are massaged. Dressed in a pink dress, she wears golden jewelry all over her body. Narayan gazes at her with admiration, drunk with love. The moon is rising amidst clouds in the background.

Lakshmi Narayan is a love scene dedicated to all the “loving, caring, and supportive husbands who stand by their halves,” as Bajracharya wrote on an Instagram post. Attributing emotion to the god was purposeful. Similarly to western cultures, men in Nepal are taught to hide their emotions from a very young age. Bajracharya’s objective was to break that idea, showing a god with a sweet romantic demonstration.

“It’s all about love and interdependence,” she said, referring to the painting as a whole.

As the homeland of the Buddha, Nepal’s society is deeply rooted in religion. However, in 2007 the country was declared a secular state. In 2008, it became a republic. This means perspectives on religion also changed. Artists embraced this change, either by welcoming western influences in their art or by proposing a more critical view of religion.

Bajracharya — a feminist artist, designer of the Supreme Court of Nepal and a curator at the Judicial Museum of Nepal — is one of many Nepali artists, who, while searching for their own voices, are proposing a fresher approach to culture and religion, deviating from their country’s traditional art.

Sujan Chitrakar, the artistic director for the Kathmandu triennale 2026, said that the coexistence of traditional art with west-influenced contemporary art is a trend in the current artistic scene in Nepal. He shared that this will be a major theme in the upcoming triennale, which he is co-directing with Australian curator Natalie King.

“The trend of looking back to your own roots and also trying to reconcile with what we have gotten from the west or even global influences, that part is exciting to see,” he said.

The triennale might be far, but other art shows are already exploring the idea of coexistence. Lakshmi Narayan was on view at the Nepal Art Council gallery as part of Deities of Nepal II — a comparative exhibition that aimed to find a balance between the voices of Nepal’s traditional and contemporary art, examining the different ways in which artists portray gods and goddesses.

From golden sculptures to etching prints to projections on walls, the exhibition featured a wide range of artforms. While contemporary pieces showcased the deities in non-seen-before ways, just like Bajrachaya’s Lakshmi Narayan, the traditional ones severely followed a set of rules.

Chitrakar said that these contrasts have historical roots tied to education. The overwhelming majority of ancient Nepali art was done by monks, who were trained in the monasteries to do rigorous, faith-driven artworks.

“There was no room for any kind of self-expression,” he said.

Examples of this strict religious art can be spotted on a quick stroll through Hanuman-Dhoka Durbar Square, one of the holiest places in Kathmandu. The square, where countless pigeons found home, was full of temples that follow the same pagoda-style architecture.

Nestled into the corner of a small alley, the entrance to an art show was almost unnoticeable. Inside, seller Dev Shrestha and guide Rama Rama tried their best to sell mandalas to tourists. The red walls of the shop were barely visible, as they were all covered by tapestry, mandalas and pictures. It was hot inside, a fan ventilating the tiny store. Shrestha was sweating, displaying multiple mandalas on the table, one on top of each other.

Shrestha said that the mandalas were made by monks in the Everest region. As he explained the hidden meanings of one of them, it was hard to distinguish what were factual explanations about the painting from what were details invented by a merchant to sell a story in the form of art.

Pointing to the cockerel, the snake and the pig inside the samsara, the central circle where all human life is contained, he explained that these three animals respectively represent desire, anger and ignorance — all three of which humans must get rid of to be enlightened with nirvana, a peaceful place.

“Buddha did it,” Rama Rama, who was sitting in the back, said, arguing that it wasn’t impossible to do so.

It is true that, in the Buddhist tradition, humans reach nirvana with the elimination of desire, anger and ignorance. It is also true that these three are represented by the cockerel, the snake and the pig.

However, skepticism filled the air when Shrestha said that they money spent on the mandalas would be sent to reconstruct monasteries destroyed in the 2015 earthquake — an affirmation that conveniently fit the high price he was selling the mandalas for. He offered one for $350, emphasizing that it was priceless in the U.S. and the U.K.

“Your house will become a museum,” Rama Rama said.

Regardless of whether or not Shrestha’s price expectation was fair, all the mandalas clearly followed a rigid set of rules. They were all symmetrical and, apart from small shifts in the color patterns, pretty much the same.

Shresta might have invented stories for commercial purposes, but it was evident that he understood the mandalas. Looking at a picture of himself painting, he said that he studied for 10 years in the monasteries, which he started attending when he was around 14 or 15 years old.

“I learned a lot of these kinds of things from there,” he said.

Chitrakar explained that, for a long time, monasteries were the only form of art schools in Nepal, forcing many of the nation’s artists to seek education abroad in countries like India, Bangladesh and Russia. He said that, in the mid- to late- twentieth century, most Nepali artists went to France and other countries in western Europe, leading to a loss of identity in the art of Nepal.

“They brought in very much western influences, especially this European academic art,” he said.

Bajrachaya didn’t hide that she draws from western ideas. Inspired by Raymond Loewy’s “Most Advanced Yet Acceptable” — MAYA — principle, she did a series of remakes of classics such as the Mona Lisa, Last Supper and Girl with a Pearl Earring. The concept was to recreate famous paintings aiming to raise awareness of different themes such as cancer, climate change and sexism.

“If we give something very new to people, they won’t be able to digest it,” she said. “But, if we modify a little bit of an old thing, then people will be able to accept it and grab it.”

One of these pieces hangs on the red wall of her living room. Birth of Fear is a recreation of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus that Bajracharya made to bring awareness to sexual harassment and to the misogyny ingrained in Nepali society and culture.

In the original painting, two male figures gaze at Venus with admiration and a female figure, which represents the Hora of Spring, wraps her in a piece of fabric, welcoming her to the world. In Bajracharya’s version, one of the male figures whistles and looks maliciously at Venus while the other stretches his arm to touch her. The female figure represents a society that so quickly blames the victims of such violence, claiming that they were wearing inappropriately short clothes or that they teased the men into hurting them.

Bajracharya completed most of her education in Nepal, but, in 2019, participated in the American Arts Incubator exchange program in San Francisco, where she learned about virtual and augmented reality in the arts. While she agreed that the traditional art is chained to Nepal’s artistic identity, she argued that western influences, which also come from social media, are positive because they keep Nepali art moving.

“Change is always beautiful,” she said.

She added that the golden era of Nepali art might have been golden for art, but not so much for artists, as most of them didn’t get credit for what they created. She speculated that this is perhaps the reason why traditional Nepali art got mitigated, saying that giving more attention to the golden era artists could have inspired a new generation to surge.

“We forgot to promote our own art, we forgot to appreciate our own art,” she said.

Now, there are three art schools in Nepal, all offering bachelor’s degrees and two offering master’s degrees. Chitrakar is one of the founders of one of them: the Kathmandu University School of Art and Design. To him, the existence of these institutions are changing the artistic scene of Nepal since they give artists the room for self-expression that doesn’t exist in the monasteries.

“The best part of art education is it gives them room for them to find themselves,” he said.

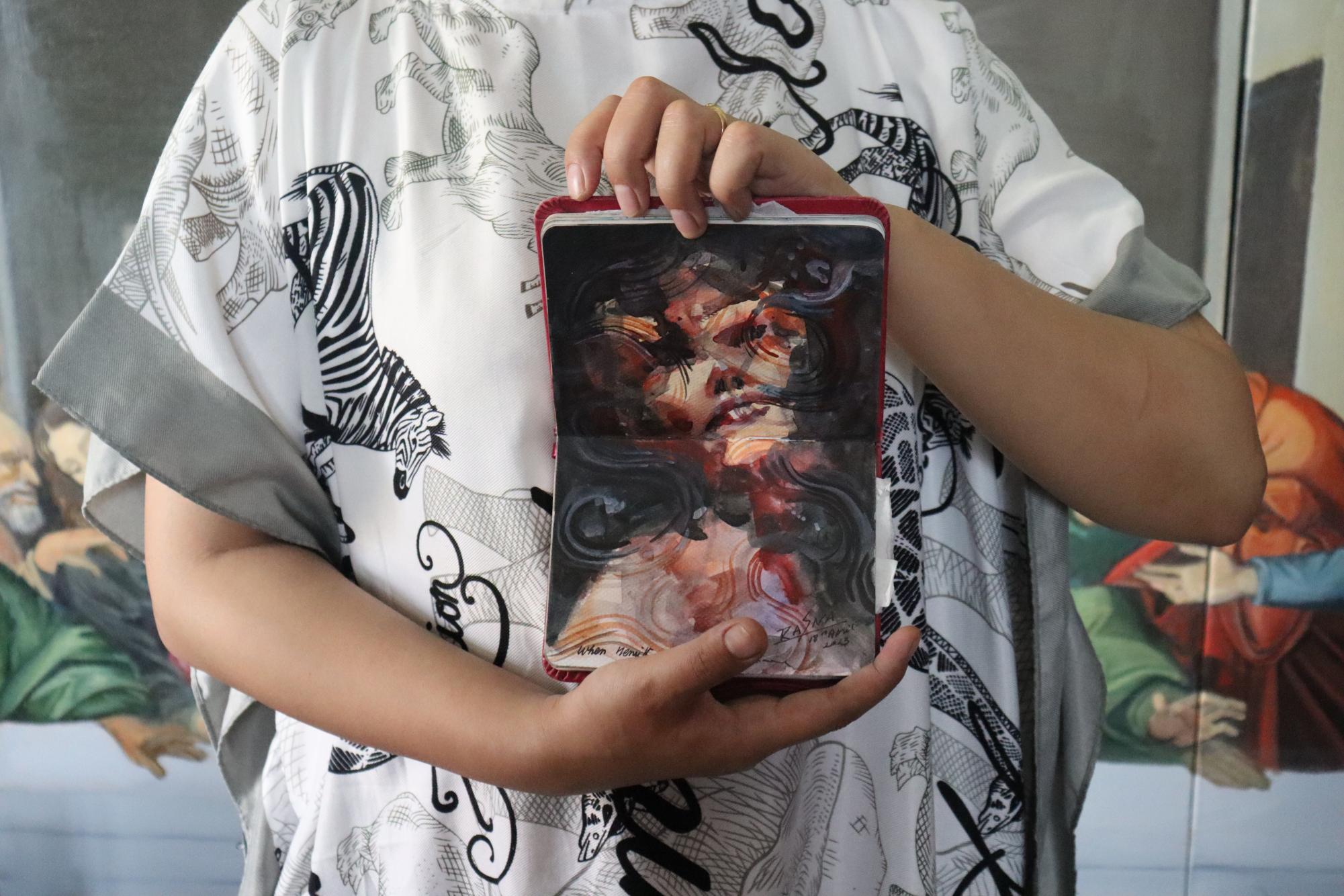

A fundamental part of this room is giving the younger generation of artists freedom to criticize taboos and practices linked to religion. For her BFA final show, Sujata Khadka made 84 drawings of vaginas with excerpts from a Hindu book printed on them. Named YONIHARU, the Nepali word for vulva, the piece criticized the sexism of some Hindu beliefs.

The 84 drawings symbolize the 8.4 million animal lives that a soul can have. Printed on them were excepts from Svasthanivratakatha, which she said is “just like a god” for some Hindus. Khadka said she grew up naively reciting the book. When she got older, she realized how heavily it emphasizes that a husband is everything in a woman’s life, an idea that drastically differed from the reality of her mother.

“I saw her struggle after her marriage,” she said.

Khadka’s mother, who married at the age of 21, found little support from her husband when raising their three children. In Nepal, women typically move in with their in-laws after marriage, but Khadka’s mother didn’t get any support from hers because they were dead. She received help from her own parents, but, ultimately, had to raise her children alone.

Raised in a Hindu middle-class family in Lalitpur, Khadka grew up watching the struggles of women in her life. These women became an inspiration for her, as she hopes to bring awareness to how tough it is to be a woman in Nepal because of marriage, cultural and religious expectations.

“I think that art has the power to address those kinds of issues,” she said.

Although they may not be immediately recognized as vulvas, Khadka’s drawings are bold. Made with pen and ink, their black and white colors stand out against the maroon background. Even to an ignorant eye, the printed excerpts add an interesting layer to the piece.

The drawings’ audacity reflects Khadka’s boldness in making them in the first place. Although Nepal is pretty much a free country, criticizing religious authorities can come at a high cost.

Stating that “no person shall outrage the religious feelings of any caste, race, community or class by words, either spoken or written, by visible representation or signs or otherwise,” the country’s blasphemy law poses a constitutional limitation to criticizing religion. Any person found guilty of this crime may be punished with up to two years in prison and a maximum fee of 20,000 rupees.

Khadka didn’t hide that, on the night preceding the opening of the exhibition, she was anxious thinking bout the potential backlash she could receive. She called her brother, who stressed to her that she didn’t do anything wrong. She held onto her belief in artistic freedom.

“[I] have the right to express whatever [I] feel,” she said.

According to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, Nepal’s blasphemy law is inconsistent with international human rights law. Bajracharya said that, because of this law, she has to be very careful when criticizing religion.

“We have to use euphemism,” she said.

This skepticism led her to change the name of one of her paintings. Purity of Impurity rejects the menstruation taboo seen in Nepal and other South Asian countries, where periods are seen as a sign of impurity.

Growing up in a Buddhist family, the menstrual education that she received from her mother and grandmother was related to religion, not health. She was told that she couldn’t touch men or go to temples and school while on her period. Additionally, she said that her in-laws, who are Hindus, forced her to eat on the floor when she menstruated.

Purity of Impurity also questions the fact that the Hindu god of creation, Brahma, is a male. While both male and female are necessary in the procreation process, Bajracharya emphasized that it is the woman who goes through most of the pain of creating a life, periods being a part of that.

“If there were a god of creation, it would be female as well,” she said.

On the lack of one, Bajracharya painted her. With long hair and a confident look, the god is shown wearing minimal clothing over breasts and her vagina. She floats against a bloody red background. Below her, Bajraharya painted lotuses, which symbolize purity in Buddhist and Hindu culture. Bajracharya originally thought of naming the painting “Brahma.”

The sacred and the profane complement each other in the formation of Nepal’s artistic identity. They are contrasting, but they can’t eliminate each other. Instead, they coexist.