Walk through the old-world streets of the East Village and you may find Benton McClintock with his phone outstretched from his face filming a TikTok.

During the Great Depression, and into WWII, Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered fireside chats through the radio in an effort to connect with millions of American homes. McClintock’s style isn’t too far off. He tells it like it is to his audience of over 100,000. His daily updates, whether parodying his job as a waiter, his frustrations or his love life feel like you’re on a one-way FaceTime call with your best friend.

“People comment on my voice a lot,” McClintock says. “So that’s been a topic lately.”

Every budding star needs a defining feature — Kim Kardashian has her butt, Justin Bieber has his hair, and Fran Drescher has her voice. Like Drescher, McClintock’s tone is borderline nasal and echoes with a feline hiss. The sharpness of his cadence would never reveal he spent a chunk of his childhood in North Carolina.

In one video, he goes on about his time flirting with a guy at a party. Leaving to the bathroom for an encounter with another one, he then resumed his chat with the original bachelor who asked where he had gone off to.

“‘I was hooking up with that other guy you saw me talking to,’” he said to the growing audience of 480,000 people who watched the video. “I literally just said that to him, didn’t even attempt to lie…and he still went home with me. Honesty is the best policy, you guys.”

McClintock’s views on his sex life weren’t always so nonchalant.

When most teenagers become sexually active, their biggest worries might be effectively covering the hickeys on their necks. McClintock worried about dying from AIDS.

Even the slightest symptom of a cold would be enough to trigger “a rotting pit” in his stomach.

“Oh my God, what if that person lied to me,” he would think. “And you just start spiraling.”

McClintock’s paranoia took over his fingers as he scoured the internet for answers in his earliest years of becoming sexually active.

A standard rapid HIV antigen test can usually detect the virus in your body 18 to 90 days post-initial exposure, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The month or so of waiting before getting an accurate test result left McClintock in a state of anxiety.

“I don’t really eat when I’m having that much anxiety,” he said. “So then I lose weight. And then I drink. Yeah, I just spiral.”

By the time McClintock became sexually active, PrEP, a popular prevention medication that can reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by around 99 percent, was available after being approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012.

While enough time hasn’t passed to evaluate PrEP’s long-term health effects, McClintock finds swallowing the daily pill pacifies his contagion nightmares.

“If I die because some weird pill I took in my 20s, you know, just decided to give me a random heart attack later in my life, that is an anxiety I can deal with,” McClintock said.

But was his initial fear of catching HIV through sex with men rational? In 2019, almost four decades after HIV became known in the U.S., 70 percent of new HIV infections in the country were among gay and bisexual men.

McClintock’s middle school sexual education experience in North Carolina didn’t help.

“The gay section was about five minutes,” he said, remembering his 12-year-old self, sitting inside the school’s outdoor trailer designated for sex ed.

“They basically just said that homosexual intercourse will result in diseases and one of those diseases includes HIV and AIDS and you will die.”

While McClintock is part of the latest generation of gay men to experience the fear of HIV/AIDS that follows sexual maturity like the sourness that comes after biting into a caramelized green apple, for at least three generations before his, gay men were engulfed in battle against HIV — and there was no pill to escape it.

Eric Sawyer moved back to New York fresh out of graduate school at the University of Colorado Boulder at the age of 26. It was 1980.

An upstate New York native, Sawyer would make trips into the city throughout the ‘70s as a student. It was a time of sexual freedom for the gay community, at the height of the sexual revolution. Formerly life-threatening syphilis was then widely treated with penicillin, crabs were wiped out with concoctions targeting lice and, “You couldn’t get a man pregnant,” Sawyer said, minimizing the need for condoms within the community.

With this sense of liberty, gay sex was found anywhere and everywhere.

“In public parks, in public bathrooms, in back rooms at bars and bathhouses,” Sawyer remembered. “There were even stairs, in particular office buildings in Midtown where you could go in a particular stairwell and get a blow job or literally have sex during lunch hours or after work.”

It was in the late ‘70s that Sawyer believes he was infected with what is now known as HIV. By 1981, the CDC released an article detailing a rare pneumonia, Pneumocystis (PCP), in five previously healthy young gay men in Los Angeles County — considered the first official report of AIDS, the advanced, stage-three form of HIV, in the U.S.

With no name or reasoning for the virus, terminology like “the 4H disease” emerged, standing for homosexuals, hemophiliacs, Haitians and heroin users — groups perceived to be most at risk.

Sawyer remembers the early ‘80s as terrifying. Nobody in the community could understand why or how young gay men at the “pinnacle of health” were coming down with PCP or purple skin lesions, a sign of Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) — a cancer indicating a weakened immune system due to AIDS.

Through waves of uncertainty, gay professionals and allies started community-based research trials in an attempt to understand how to stop the spread of the virus, which was called Gay-Related Immune Deficiency in 1981 before being named Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) by CDC in 1982. A popular booklet, “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic” is credited as one of the first to advocate for the use of condoms as safe-sex practice.

Both church and state fueled HIV/AIDS stigma. Prominent televangelist Jerry Falwell said AIDS was God’s punishment for “homosexual promiscuity.” The Catholic Church preached against using condoms for protection. And Senator Jesse Helms spewed homophobic rhetoric from the U.S. Capitol.

Views on the epidemic hit a turning point when Hollywood icon Rock Hudson announced he had AIDS in July of 1985, one of the first public figures to do so.

It took then-President Ronald Reagan, a friend of Hudson’s, four years into the epidemic and thousands of deaths later, to publicly mention AIDS for the first time that September. Within a month after, Hudson was dead at age 59.

“It wasn’t a junkie. It was a faggot. It wasn’t a Black person. It was one of America’s greatest heartthrobs and movie stars, and I think that changed public perception a lot,” Mark Marino, a long-term HIV survivor, said.

By 1984, Sawyer was the primary caretaker of his partner, Scott Bernard, who was diagnosed with KS, now known as an indicator of AIDS, while simultaneously dealing with confusion about his own body. He was experiencing lengthy flu-like symptoms prior to his move to New York in 1980. He had also developed swollen lymph nodes, which his doctor found concerning as it was also seen in gay men who had died from PCP.

Sawyer was formally diagnosed with HIV in 1985 when his doctor sent a sample of his blood under Bernard’s name. Upon Bernard’s death in 1986, Sawyer called Larry Kramer, one of his first friends in New York, to tell him the news.

Kramer, a famed writer-turned-leading-activist, was deeply involved in advocacy regarding HIV awareness and recognition. He co-founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, just one of the various non-profits which sprouted rapidly in the gay community.

When Sawyer told Kramer about a neighbor who was fired because they had AIDS and were facing homelessness, Kramer invited him to a gathering he was holding at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center in Greenwich Village — the beating heart of New York’s gay scene and the epicenter of AIDS on the East Coast.

“He was going to give information about how research money that had been allocated by Reagan wasn’t being used to actually try to find treatments for HIV because there was a hiring freeze at the National Institute of Health imposed by Reagan,” Sawyer said.

“Larry wanted to start a civil disobedience organization to draw attention to this fact and put pressure on drug companies and the government to try to find a cure.”

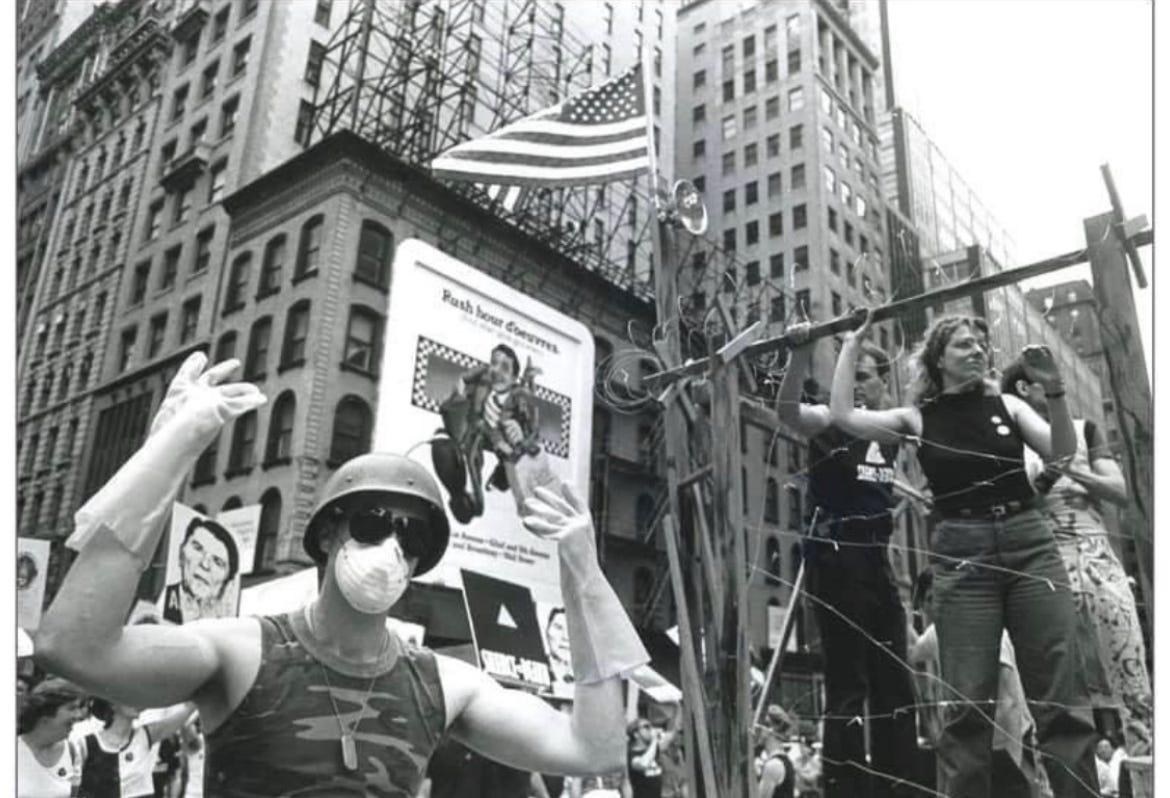

Just a few blocks over from the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, ACT UP, or the AIDS Coalition in Power, was born. Their slogan: “United in Anger.”

Anger over hospitals turning away HIV patients and disposing of bodies in black trash bags. Anger over officials not declaring AIDS a public emergency. Anger over the FDA taking too long to approve potentially life-saving drugs.

It wasn’t long after ACT UP’s inception in 1987 that NYC Mayor Ed Koch condemned the group for their “fascist tactics.” While building a like-minded community with ACT UP, Sawyer was facing losses in his professional life.

As the epidemic spread and the virus mutated, Sawyer hopped from one clinical drug trial to the other, soon discovering that the conservative firm he worked for wanted to fire him upon learning he had HIV. He recalls being moved from consultant departments to research ones to limit his interactions with clients. When his T cell level was low enough to qualify for an AIDS diagnosis Sawyer was placed on long-term disability leave. He threatened to sue.

“They basically said, ‘You know, you have a fatal disease that your life expectancy is only a couple of years,’” Sawyer said. “Everybody else in our unit was married with kids. You know, wouldn’t I feel bad forcing one of those people to be fired in the downsizing, or laid off, when they had children and when I probably wouldn’t live for more than a year or two anyhow.”

Sawyer consulted a lawyer who validated that he was facing discrimination and could potentially win a lawsuit, but that “he’d be dead before it ever got to court,” Sawyer said. He ended up taking the disability leave that granted him about 60 percent of his salary and health insurance — his newfound free time allowed him to put his energy into ACT UP, before co-founding Housing Works in 1990.

By 1989, AIDS was the leading cause of death in men aged 25 to 44 in New York City. By 1990, nearly twice as many Americans had died of AIDS as died in the Vietnam War, according to the NYC AIDS Memorial. Still, a new generation of gay men were moving to New York City.

Mark Marino, a pseudonym for the now celebrity makeup artist who wishes to remain anonymous for the potential stigma he could face with his employment, was one of them. Marino, a New Orleans native, was diagnosed with HIV in June of 1989 at age 23.

After being advised by a dermatologist to get tested for HIV due to his swollen lymph nodes, Marino called back to check the status of his test.

“It was just basically, ‘Thank you for calling, your test came back positive.’ Click,” Marino remembered. He then backpacked through Europe for two months, “I wanted to see the world before I died,” he said.

Upon settling in New York City in the early ‘90s, Marino encountered a vibrant gay scene, even though death was always lingering.

“I was such a like punk rock kid, like, I looked so strange, probably to most people. And I just remember first coming to New York and landing in the East Village and looking around and saying, ‘Okay, this is my tribe, these are my people,” Marino said.

He recalled how the nightclub crowd became like family. As well as hubs to dance, perform and escape the realities of the epidemic, nightclubs reflected the politically active climate within the community — flyers about safe sex and the latest treatments were frequently distributed, Marino said.

“It wasn’t about the sex as much anymore as it was about the music. And just being with your community and trying to forget for those few hours about what was going on in the outside world,” Marino remembered.

But once night turned to day and the dancing stopped, it was impossible to ignore reality.

“Probably from ‘89 to ‘92, I would say over 50 people I knew died,” Marino said. When asked how he got through it, he paused before answering: “I don’t know, you were just in survival mode.”

Tom Viola, executive director of Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS since 1997 — the theater community’s leading nonprofit and response to the epidemic — recalls the virus’ impact on creatives and performers. The biggest loss, he says, is in that unknown.

“Everybody knows the artists who were at the height of their career who passed…but what folks don’t know are the folks who were just coming up, who were just beginning to express themselves, just stepping into careers. Their creativity and what could have been genius was cut short,” Viola fervently said.

By the mid-1990s, HIV treatment was experiencing a major turnaround. Researchers discovered that a triple-drug therapy — known as antiretroviral “cocktails” — was working to bring viral loads down to manageable levels and prolong life expectancy by 1996. This was the first time a treatment seemed to work, and last, for HIV/AIDS patients.

The emergence of triple-drug antiretroviral therapy was described as having a “Lazarus effect” on HIV/AIDS patients, referring to the biblical story of Lazarus coming back to life after dying of illness.

“The advent of triple therapy, involving a couple of antiretrovirals with a protease inhibitor, allowed my immune system to dramatically rebound my T cells,” Sawyer, whose T-cell count fell below 200 into the AIDS range, said. Normal T cell counts in adults range from 500 to 1,200 cells.

“I had wasting syndrome and a number of things like fungal infections and hairy leukoplakia and recurring shingles…But I never came down with pneumonia or Kaposi’s sarcoma, luckily, and so I managed to survive until the protease inhibitors came around.”

While there was a newfound sense of hope for HIV/AIDS by the end of the ‘90s, issues pertaining to the virus, and the stigma surrounding it, seeped into the 21st century.

When Robert Suttle was enlisting into the U.S. Air Force, an HIV-positive diagnosis was not the outcome he expected.

Just shy of graduating college, then-24-year-old Suttle had never been hospitalized or faced any major health issues. When a letter requiring him to return to the processing center vaguely mentioned it was health-related, it left him surprised and anxious.

“They took me into this office, and they sat me down, and they began to talk and tell me that I was HIV positive, and therefore I wouldn’t be able to enlist or continue to enlist,” Suttle said. “The last thing I remember the doctor saying was that I could go on and live a healthy life.”

Suttle, a Louisiana native, didn’t tell his family right away.

“Living in the South and being raised in an African American community, like it’s something that, and as a gay man, is something that we don’t necessarily talk about publicly because of stigma and shame,” Suttle said.

Although Black people made up 13 percent of the U.S. population in 2019, they accounted for over 40 percent of HIV infections. 62 percent of 2019 HIV infections within the Black community are attributed to men who have sex with men, according to CDC.

Suttle’s family eventually learned his status. But not on his terms.

In 2009, Suttle was prosecuted and convicted in a Louisiana court for intentional exposure to the HIV/AIDS virus.

While in a three-month casual relationship with a male partner, Suttle, who says he was receiving HIV treatment at the time, engaged in unprotected sex. Before making the consensual decision to do so, Suttle said he disclosed his HIV-positive status.

Toward the end of the relationship, he was “confronted” during a three-way conversation between a mutual friend who knew his status and his former partner, where Suttle said he disclosed he was positive again. His former partner pressed charges soon after. Suttle was imprisoned for six months after pleading guilty because he “wanted it to be over.”

“People think that oh, if you disclose you’re okay. And that’s not true,” Suttle said. “What happens in these cases, when people are being accused, they’re most likely to face conviction. Nine times out of 10.”

The 35 states with HIV-or STD-specific criminalization laws can oftentimes prosecute a person living with HIV without actual transmission of the virus or intent to spread it. Exposure is enough — a knowingly HIV-positive individual accused of intentionally exposing their partner to the virus may face up to 10 years in prison in Louisiana. As recently as 2017, grounds for potential prosecution include no-to-low-risk activities including spit exposure, like oral sex.

“This was like the perfect storm being someone who is HIV positive. Being Black, gay, and someone who’s living with HIV and also being subjected to the criminal justice system,” Suttle said, as HIV criminalization disproportionately affects Black men in Louisiana.

14 years later, Suttle’s past burdens him daily.

After his imprisonment, Louisiana required he register as a sex offender for 15 years. Although no such HIV-specific law exists in New York, the state decided Suttle had to register there after he relocated under protocols of the NYS Sex Offender Registration Act.

Suttle, who would ideally be able to get off the Louisiana registry next year, said New York does not appear to account for the overall time he’s spent listed as a sex offender, leaving him “stuck.” In late 2022, Suttle asked the NY Court of Appeals to reverse the lower court ruling requiring him to register as a sex offender in the state because of a law from a foreign jurisdiction, according to the amicus brief filed by the Center for HIV Law and Policy.

“It’s not just for me, it’s for many people who may experience this,” Suttle, who works with organizations like the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation, said about pushing for the appeal.

“People who are marginalized, people who are impacted by HIV and incarceration, they want to live full lives. They want to live lives that are not oppressed.”

In May, the NY Court of Appeals denied hearing Suttle’s appeal, leaving the lower court ruling in effect. Exhausting all his options in New York, Suttle says he might return to Louisiana to petition his removal off their registry when his 15-year requirement is up in 2024.

During the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the global response was swift. Nations closed their borders, cities transformed into fortresses and going outside without a mask felt like entering Chernobyl without a hazmat suit.

Yet, the American public’s initial acceptance of social distancing and following other CDC guidelines was largely due to the influx of information streaming out of all forms of media. From coronavirus’ initial declaration as a pandemic, it was immediately addressed by the government, national health institutions and mainstream publications.

Members and researchers of the LGBTQ+ community see these transparencies as a legacy of HIV/AIDS activism.

“We really have to thank the courageous activists who put their lives and their bodies on the line in the 1980s and 1990s around HIV and AIDS for the notion that public health should be something that’s more democratic and participatory.”

ACT UP was forceful in gaining the attention of the nation’s largest medical institutions— the FDA and the National Institutes of Health. Their goals ranged from accelerating the approval and distribution of experimental drugs to including women and people of color living with AIDS in clinical trials.

In 1988, around 1,500 ACT UP protesters flooded the Food and Drug Administration headquarters demanding quicker approval for treatment drugs — following regular procedures, approval took around seven to 10 years. Activists set off a smoke bomb, smashed a window, hung an effigy of Ronald Reagan and laid on the building’s steps with cardboard tombstones before police began corralling groups into buses for civil disobedience, according to a report. The event garnered mass media attention but also led to greater understanding of the needs of people affected by HIV/AIDS from the medical community.

“I wouldn’t use the term, ‘Win them over,’” Sawyer answered when asked about the intended outcome of these demonstrations. “I would say hold their feet to the fire, and embarrass them and make their lives uncomfortable unless they started responding appropriately and with a sense of urgency.”

Protests demanding officials recognize and research COVID-19 weren’t necessary. The Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccine was available less than a year into the pandemic, gaining FDA authorization in August of 2021.

“It was infuriating to see the city and state ramp up our response to COVID since it affected everyone and not just one community,” Brandon Cuicchi, who joined ACT UP after developing a zeal for activism during the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, said.

The safety and accessibility of early COVID-19 treatments in Western nations starkly contrasted the first FDA-approved drug for HIV/AIDS treatment, AZT — then a form of discontinued chemotherapy developed in the ‘60s.

Greenlit at record speed in 1987, AZT had no competition. Its distributor, Burroughs Wellcome, set the price at $10,000 a year, the most expensive prescription drug in history at the time.

AZT alone, however, was not viable. For some only taking AZT for HIV, drug resistance developed in a matter of days, the NIH noted. Side effects included nausea, anemia and low white blood cell counts.

“It was a very bad drug,” Marino said. “Almost all of my friends who took AZT ended up dying.”

While FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccines rapidly sprouted from pharmaceutical companies, after over 40 years — and over 40 million global AIDS-related deaths — of HIV/AIDS, there are no effective HIV vaccines to prevent or treat the virus.

A medical article lists HIV evolution as the highest recorded biological mutation rate currently known to science. When the virus enters the body, it attacks and destroys white blood cells (CD4 or T cells) that protect against infection — thus weakening the body’s immune system.

“The virus mutates so totally, and so quickly, that it’s been impossible to create a vaccine. And without a vaccine, I don’t think we will have a cure for HIV,” Sawyer, a UNAIDS retiree, says.

In January of 2023, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, under Johnson & Johnson, discontinued the only current late-stage clinical trial of a prevention vaccine because of ineffectiveness.

Sawyer, who’s been living with HIV since being diagnosed in the ‘80s, doesn’t believe he will live to see the day HIV is cured. He says drug companies don’t have the incentive to find an effective vaccine because of the profits generated from HIV prevention and treatment medications.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART), the combination of multiple antiretroviral drugs that target parts of the seven stages of the HIV life cycle to control and reduce the virus in the body, remains the most effective and popular form of HIV treatment. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 75 percent of HIV-positive people globally in 2021 were receiving ART.

While not a cure, ART is successful at prolonging the lives of people with HIV/AIDS and reducing HIV to undetectable levels — meaning the virus still exists in the body but lacks the abundance to appear on HIV tests or transmit through sex, as long as the medication is taken as prescribed.

HIV-positive individuals must take HIV pills every day for life to keep their regimen effective — missing a dose gives the virus a chance to multiply and increases the risk of drug resistance.

Yet, these life-saving medications aren’t cheap. Average undiscounted lifetime HIV-related medical costs for HIV-positive Americans are over $1,000,000, according to a 2021 study. Biktarvy, a triple-drug antiretroviral in the form of a once-a-day pill from leading HIV pharmaceutical company Gilead, has a wholesale price of $3,795 a month. Insurance can cover the cost, but the U.S. government currently has no right to negotiate market drug prices set by pharmaceutical companies.

“You have to pay basically $1,000 a month for health care to maintain your health just to get these drugs,” Marino, who’s changed his HIV drug regimen multiple times and is currently taking Biktarvy, said.

“I think I will always be able to get the drugs. I think, though, the drugs could force me into poverty by needing to have these drugs.”

For the uninsured, federal and state-funded programs like Medicaid or AIDS Drug Assistance Programs (ADAP) can also help cover the cost of medicine, but to qualify, individuals must be low-income — with many recipients living below the poverty line.

“It’s forced poverty in a weird way,” Marino says.

COVID-19 also took a toll on New York City’s sexual health clinics. Seven out of eight city clinics closed their doors. As people with advanced or untreated HIV are at increased risk of serious illness from Covid, losing access to the clinics meant less testing, prevention and treatment availability — nearly one in five people with HIV do not know they are positive. During the first year of the pandemic, CDC-funded HIV testing in health care settings dropped by 43 percent from the previous year.

With limited service came longer wait times, and clinics reached capacity well before closing time.

“You couldn’t get same-day or next-day service,” Cuicchi said.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), the emergency medication that works to prevent HIV infection, must be started within 72 hours of possible exposure to the virus. With clinical treatment becoming a waiting game, HIV prevention was at risk for vulnerable communities who benefitted from the clinic’s low to no-cost services for the uninsured.

NYC’s sexual health clinics eventually reopened in November of 2022. A viral disease disproportionately affecting men who have sex with men broke out first.

Mpox (formerly monkeypox) isn’t a new virus, but the recent outbreak in May of 2022 saw it spread outside the western and central African countries where it’s considered endemic.

Mpox can affect anyone, but its prevalence among gay and bisexual men reignited homophobia akin to the AIDS era from conspiracy theorists and politicians alike — particularly that gay sex is solely to blame for the spread of mpox, a false claim that overlooks the virus’ potential to spread through something as simple as the clothing of someone infected.

“During COVID, people came back to ACT UP very angry. For monkeypox, people came back to ACT UP very angry,” Cuicchi said. “I think as long as we’re a vulnerable part of the population, our anger will always be there.”

As with COVID-19, people with advanced, untreated HIV have a higher risk of severe symptoms or death from mpox. U.S. infections have steadily declined since peaking in August of 2022, aided by the availability of smallpox vaccines and medicine used on mpox. According to the WHO, most people recover from mpox within two to four weeks.

“I was not nearly as worried as I was when AIDS was happening,” Marino, recalling his initial thoughts on mpox, said.

“I worry that you’ll have another epidemic of some sort, and then no one’s gonna have any pity on the gays at all,” citing the growth of antibiotic resistance in STIs like syphilis and gonorrhea.

Marino correlates the popularity of PrEP with the growth of unprotected sex in the gay community, akin to the relaxed practices prior to HIV/AIDS.

“Prior to 2014-15, sex without condoms was strongly stigmatized, seen as sort of a dangerous subcultural practice,” Shepard said.

“Within just five or seven years, that has changed dramatically…folks who insist on safer sex practices from a different generation often find themselves feeling excluded or stigmatized.”

Andrew Bailey, 53 and a generation removed from the first wave of gay men to experience HIV/AIDS, notices this shift. Bailey moved to NYC in the early 1990s and remembers having a “fatalistic approach” to sex, like a game of “Russian roulette,” throughout his 20s.

“I feel envy, a little bit of jealousy, because I could never have done that when I was 21 years old. That was a death sentence,” Bailey said.

He credits the September 11 attacks, when he was in his 30s, for easing his views on sex.

“Everyone thought it was the end of the world and you might as well go down having fun,” Bailey chuckled. “On the rare occasion that I go out in New York City now…it’s a free-for-all and it’s like most club nights have back rooms.”

As generational gaps grow, witnesses to the throes of the epidemic urge caution for those too young to remember or experience it.

“We should be constantly saying to ourselves, ‘Check your behavior,’ or look out for friends, look out for yourself, I don’t think we’re doing that anymore,” Bailey said.

For men who have sex with men, the location-based dating app, Grindr, is a popular choice.

Marino describes its modular grid design “like looking on a Chinese fast food menu,” with interactions feeling “dehumanizing” and “impersonal.”

“There seems to be less community now,” Marino said, reflecting on the time before the digitalization of meeting potential partners. “I liked that idea of having to go out and be with your community. I feel like we had more respect for each other before these apps.”

McClintock, born a couple of generations after Marino, describes his upbringing as “chronically online.” Although he didn’t experience a time without apps like Grindr, his views on gay culture today echo a similar message.

“Gays [are] being scared to talk to one another sometimes because of how one might look and the way that’s perceived and things of that nature,” he says.

“I just wish we could all get along.”

Asthe community grapples with issues like racial disparities among PrEP access, the commercialization of Pride, and anti-LGBTQ legislation sweeping the nation, survivors of the epidemic reflect on where they fit in the 21st century.

“Do I feel like we’re forgotten?” Marino pondered when posed the question. “Sometimes, yes.”

For Sawyer, feelings of survivor’s guilt only fueled his HIV/AIDS activism — from being a founding member of ACT UP, co-creating Housing Works, working with UNAIDS, Gay Men’s Health Crisis and more.

“You wonder, why did I survive when so many of my peers and friends didn’t,” Sawyer pondered. “I have an obligation to all of those who didn’t survive to invest what time I have in making sure more people survive.”

Sawyer says his biggest hope is for everyone in the world to have equitable access to health care someday.

Like a rainbow that emerges when sunlight pierces thick storm clouds, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and the action it spurred, ushered societal acceptance.

“People’s families realized that they had brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, parents, cousins, coworkers, church members, friends, whatever, who are gay than they were aware of when people were more closeted,” Sawyer said.

“Gay people are kind of everywhere, and everybody knows, probably loves somebody who’s gay, or lesbian, or bi, or trans, pick a letter.”