Renée Kann Silver is a 92-year-old woman.

The bookshelves of her Garden City home are piled high with literature.

She loves to drink tea.

She adores quilting.

Her two cats are her pride and joy.

She is also a Holocaust survivor.

In 1940, Silver and her family spent the months of May through June in the Gurs, France concentration camp.

While there isn’t an exact number of how many Holocaust survivors remain, time is running out to capture who they are as human beings and to be in the presence of the people behind the statistics. Most survivors are in their 80s and 90s, which means that each year, fewer witnesses remain to tell their stories.

However, Silver disagrees with that sentiment. She said there is a growing movement to preserve the stories of the Holocaust.

Silver said she found hope within the work of Elie Wiesel, a fellow survivor, who dedicated his life to educating the public about the atrocities of the Holocaust by authoring dozens of novels.

She said new witnesses can be created, rather than forgotten, through the sharing of stories.

“Look, I know I’m not going to be presenting this [history] forever,” she said. “The idea behind this work is that by being a witness, you become a witness.”

What Silver means is that you don’t have had to experience the horrors first-hand to be a witness. By learning about the Holocaust from survivors like Silver, listeners, too can become, in essence, a witness.

By “this work,” she is referring to the process of sitting down with younger generations and sharing personal stories of survival, anguish, death, and hope behind the Holocaust. However, doing so wasn’t easy for Silver.

It took 49 years after Silver was liberated to share what she went through. Not because she didn’t want to, but because she literally could not. She experienced many instances of anti-semitism which she said, “led [her] to repress many memories because of how upsetting they were to [her].” In fact, she had shared virtually nothing with her husband or her son.

The key to unlocking her memories was found in a documentary. Silver attended a screening of a film titled “Weapons of the Spirit” and saw her name, date of birth, and home address flash across the screen. The film had to be stopped because Silver let out such a loud scream.

“I can’t remember a moment like it in my entire life!” she exclaimed. “I was completely out of control!”

Her name was etched in a diary that kept track of Jewish children who were being transported from French cities into hiding. She was among 5,000 Jewish children who were taken to an isolated plateau called Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (Silver came from the commune of Villeurbanne). The children were then hidden and eventually saved by the Protestant community and neighboring farmers.

Silver said everything fell into place when she saw the film. She had always known she was involved in something horrific, but she couldn’t find the words to tell her stories. Silver is now able to articulate that she is a child of the Holocaust.

Silver speaks at high schools and colleges where she discusses concentration camps and the unbearable isolation she experienced while being hidden. While explaining the unfathomable evils she faced, she reflects on the pure goodness of some.

In order to survive, Silver encountered people who risked their lives for her. They did this free of selfish reasons, she remembered, “they helped me just because they wanted to.”

Silver calls on the younger generation, those who are genuinely interested and good listeners, to be the witnesses and storytellers for the future so that this never happens again.

Silver has gone from saying that she “spent some time in France during the war” to saying that she is a “survivor of the Holocaust.”

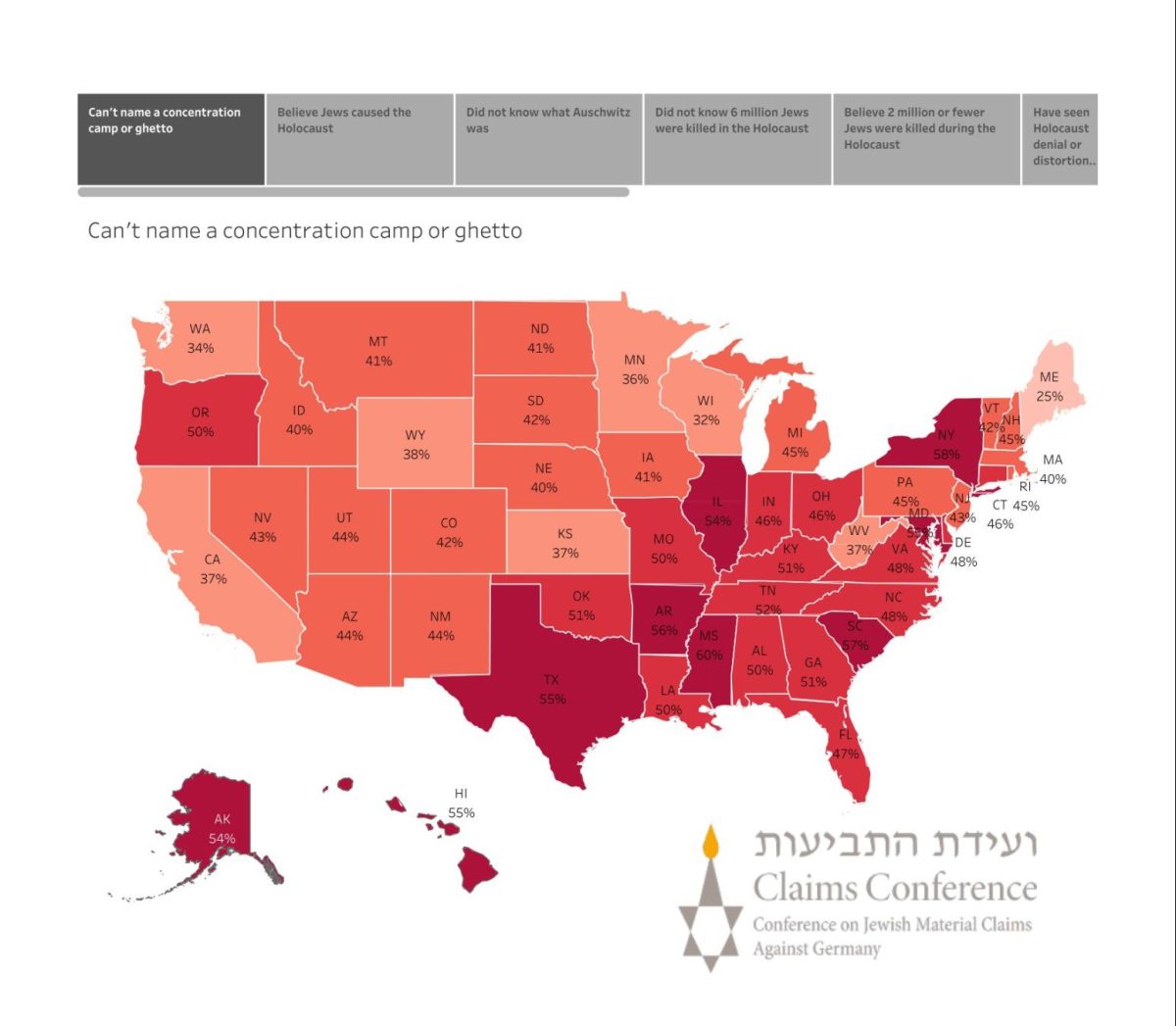

While some survivors like Silver have begun to share their stories, younger generations in the United States, such as Millennials and Gen Z, are lacking in Holocaust knowledge.

According to a survey conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), 63% of respondents did not know that six million Jewish people were killed in the Holocaust. That is more than half the population of Millennials and Gen Z in the United States.

Additionally, 56% of Millennials and Gen Z were unable to name the largest concentration camp, Auschwitz-Birkenau. Here, more than 1 million people were killed during World War II.

However, 80% of all surveyed participants said it is important to teach about the Holocaust.

A branch of artificial intelligence is one of the newer methods taking on this role.

At the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation (Shoah being the word for Holocaust in Hebrew), around 55,000 survivor testimonies were filmed through the direction of Steven Speilberg after his critically acclaimed film “Schindler’s List” was released. The historical drama focused on the horrors of the Holocaust.

Artificial intelligence at USC is taking the idea of preservation a step further through a project called “Dimensions in Testimony.”

The project not only allows people to listen back to testimonies from survivors, but to actively converse with them, even with those who may no longer be living.

The process of recording these testimonies is extensive.

Survivors are brought into a studio filled with 116 cameras designed to capture their every move. Each camera is pointed to a green screen, and in front of it is a chair where the interviewee sits. The interviewer then asks the survivor more than 2,000 questions, leaving nothing unaddressed.

The responses are not short in length, rather they are teeming with emotional in-depth stories and first hand accounts. Through speech recognition, the technology is able to “find” and “search” for the most appropriate response to the proposed question. This is done through natural language processing, a branch of artificial intelligence that allows computers to understand languages the same way humans do.

These interactive biographies are then made accessible to the public via life-sized screens in schools or museums. A smaller-sized version is available on the internet.

Questions that can be asked range from, “what was your favorite song as a child” to “how can you still believe in God given what you’ve been through?”

The recordings are complete with innate human movements: the twitching of hands, natural pauses between thoughts, even, the blinking of eyes.

The idea was first conceptualized in 2010. Production took place in 2014 with a man named Pinchas Gutter– a survivor of six Nazi concentration camps. In 1943, his mother, father and sister were all murdered in Poland’s Majdanek death camp.

Kate Canada Obrego, the director of communications and web presence at USC’s Shoah Foundation, has a “version” of Gutter in her office. The “version” being one of these life-size interactive biographies.

In a Zoom interview with Obrego, she demonstrated how people can speak to Gutter in her office.

“What is your favorite type of music?” she asked.

I like most music,” he responded, without missing a beat. “I don’t like modern classical music. I don’t like any other music but classical, opera, church music, and spiritual music.”

Obrego smiled and laughed, acknowledging Gutter’s human quirks and sarcasm that she said makes him “wonderful.”

Before she had gotten involved with Dimensions in Testimony, Obrego was a teaching assistant, research fellow, and instructor at University of Southern California’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences. She taught history courses and often had her classes read novels about the Holocaust.

She also has a personal connection to this genocide. Her family was affected by pogroms, which are massacres against specific ethnic groups (usually Jewish people). Obrego’s grandparents were in Lithuania and Poland during the Holocaust and experienced anti-semitism daily.

“When you interact with survivors it’s very challenging emotionally,” Obrego said. “I saw [my grandparents] have very difficult relationships.”

That’s why she felt it was important to, “get back into this game,” she said. “These stories have to be told.”

Obrego wants these interactive biographies to be used by the world in order to understand survivors like Gutter in a multi-faceted manner.

Virtual Interviews with Survivors

Eric Miller, an adjunct professor in the history department at Stony Brook University, said artificial intelligence is a brilliant use of technology. He has conducted oral histories with many survivors, but he knows that not everyone will get the chance to do the same.

“That’s part of what’s lost, even from doing oral histories, you can’t capture everything,” Miller said. “To dedicate that amount of time and try to think of every contingent question is a very powerful experience to have that captured.”

Miller relies heavily on bringing that personal touch into his classrooms. He says doing so enriches history, being that he is the grandchild of a Holocaust survivor himself.

It wasn’t until he lived in Israel for a number of years that he became engrossed in the history of his own family.

Since then, Miller has conducted many oral histories with survivors which he said were, “life changing.” He strives to replicate that experience for his students by showing testimonies to his classes and encouraging a level of personalization by doing so.

“To say that six or seven million people died actually means very little, but to talk about specific people and humanize it gives it much greater meaning,” Miller said.

Discussing the experiences of Holocaust survivors is the hallmark of an organization called “3GNY,” (meaning third generation since the Holocaust). Serving as a “NYC-based Group for Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors” is its mission.

At 3GNY, membership involves sharing personal stories with students, meeting survivors, touring culturally significant areas, and serving as a space for anyone touched by the Holocaust.

The organization was founded in 2005, with membership now surpassing 5,000.

David Wachs joined during the organization’s first year. He now serves on the board of directors, which he said has not only made him a better professional, but a better person.

“I have changed a lot since I have met other people who value this history,” Wachs said. “[At 3GNY] you have a shared background which connects you to these people.”

Wachs never thought about sharing his family’s history with others until he saw an advertisement for 3GNY. It detailed that people were coming together to talk about the Holocaust and the stories of their families.

Prior to joining 3GNY, he had never talked about his family’s Holocaust experience. Wachs is the grandchild of two survivors, but growing up, he never heard them speak about their experiences.

Throughout his teenage years, Wachs picked up on tidbits of conversations that his other family members were having. He started writing down pieces of his grandparent’s story and attending events where other descendants were sharing personal stories. Wachs said this compelled him to learn everything he could about his grandparent’s life during the Holocaust.

In order to do so, he interviewed his relatives that lived in France.

“I didn’t think about why I would…talk to people about this,” Wachs said. “I think the idea of keeping the stories alive is to use them for good; to use them as a tool for education.”

In 2010, 3GNY collaborated with Facing History and Ourselves, an organization that promotes learning about the past to allow for a better future, in order to create “WEDU” (We Educate).

“WEDU” trains descendants of Holocaust survivors to present their families’ stories to schools and community groups.

Over 350 descendants of Holocaust survivors have gone through this training.

Wachs said a “really good speaker” can adapt their family’s account to any group of listeners.

He said that if a grandchild wanted to mention that their grandmother had to walk barefoot in the middle of the night for 30 miles, they could then relate “the 30 miles” to points of reference that the audience group is locally familiar with, giving it that more personal touch.

Humanizing this history is also something that is being done at The United States National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. This museum receives collections and artifacts directly from survivors and liberators.

Senior curator of the museum, Steven Luckert, uses these artifacts in order to piece together exhibitions.

“It’s often reduced to six million Jews were killed during the Holocaust, but each one of those individuals had a story, a family, and something to offer” he emphatically stated. “These artifacts offer us insight into those people.”

In the museum’s permanent exhibit, which allows visitors to go through the history of the Holocaust, identification cards are provided.

These cards hold the stories of people who lived in Europe during the Holocaust. The stories contain a biography of the individual, their experiences during the war, and whether they survived. As patrons absorb the history, they are able to hold onto the unique stories of individuals, making the experience more visceral.

Holocaust survivors also volunteer to work at the museum, which Luckert said, makes the museum more personable.

Currently, there are almost 50 Holocaust survivors who volunteer at the museum.

At one point, the United States National Holocaust Memorial Museum had more than 60 Holocaust survivors who volunteered to work donor desks, translate documents and speak to visitors.

“I was able to talk to [the volunteers] on a very regular basis, to learn with them and to laugh with them,” Luckert bittersweetly remarked. “I shared stories with them and talked about their experiences. To me that was a very wonderful thing.”

As time has passed since the museum first opened in April 1993, the museum has lost many Holocaust survivors who volunteered their time. Luckert says he finds himself attending more and more funerals of those he had grown to love and cherish.

“To me that’s a very sad thing on a personal level,” he said.

As the museum copes with losing many beloved witnesses of history, survivors are encouraged to record and write down their accounts for posterity. Many testimonies have been put into every exhibit of the museum. Luckert said he is a huge advocate of doing this.

He used to regularly see a survivor who would often reminisce about jokes that a teacher of his would crack.

“Write them down!” Luckert would say. “They’re not just jokes and stories. You’re keeping alive that memory of the person who perished.”

Luckert said keeping the essence of humanity alive is what each exhibit in the museum strives to do.

One exhibit that does this is called, “One Thousand and Seventy-eight Blue Skies.” These are photographs of the skies that hung above every recognized Nazi concentration camp.

Photographer Anton Kusters took these photos between 2012-2017 while traveling through the camps in Europe.

These 1,078 murky blue skies invite museum-goers to think about the people who suffered beneath each sky.

Something as simple as the skies that history transpired under may not be taught in schools, but including an element that all of humankind can identify with is an example of what Luckert said he treasures about the museum.

“There are such personal and emotional tie-ins to this history that I hope and think people will never forget,” Luckert said. “That’s the history of the Holocaust. The human moments: the pain, fear, hope, and anger.”

Let’s chat with Pinchas Gutter, the first Holocaust survivor to take part in the Dimensions in Testimony Project. This project allows the public to speak with survivors through interactive technology.

Here he spoke about his happy childhood. He remembered how parents taught him the Polish and Yiddish languages. During our talk, Gutter expressed his enthusiasm for Dimensions in Testimony because he is thrilled that future generations will be able to learn about his experiences in such an intimate manner.

He described his time in concentration camps as “living death.” Yet he spoke about his survival, his irrevocable belief in God led him to never give up hope. Finally, we discussed his liberation, his memories of running out into vast fields as far as his eyes could see. He stood there waiting for the answer to his escape. He found that answer in two horses who suddenly appeared in his eye line. Gutter used these horses, which he described as “family,” to free himself from the concentration camps. Now, he lives to help people through doing community social work, it is his greatest purpose in life.

You can interact with survivors, as well.

Below is an evaluation that showcases the efficacy of Dimensions in Testimony (provided by USC’s Shoah Foundation)

This report reveals that those who interacted with Dimensions in Testimony had a greater sense of curiosity, understanding, and regard for Holocaust survivors than before.

Renée Kann Silver, a Holocaust survivor, was born in Saarland in 1931. At the time, Saarland was an independent territory with France and Germany as its borders. However, in 1935, there was a plebiscite which took place, deeming Saarland part of Germany. Silver’s family immediately moved to France in fear of Hitler’s regime. However, the family was arrested because the French feared that any foreigners were German spies. They were then taken to a concentration camp in Gurs, France.

Silver said the concentration camps of Gurs were unbearable for her family. There were rats, fleas, and almost everybody had lice. Silver’s scratchy straw mattress was the only place where she could rest her head at night.

After France fell to Germany in the Battle of France in June of 1940, the Germans came in and freed those in the Gurs concentration camp. The people who made up the camps were not thought to be Jewish by the Germans, but foreign spies in the eyes of the French. Even though Silver’s family identified as Jewish, the Germans simply saw them as an enemy of France.

Silver and her family were then allowed to move to the commune of Villeurbanne which is near Lyon. Here, Silver attended school. At the end of the school year, students assembled in the yard to find out which student would be awarded a book by Henri-Philippe Pétain, the head of the fascist state, Vichy France, which collaborated with the Nazi Party.

The student would have to demonstrate excellent scholastic achievement and sportsmanship in order to emerge victorious. Students and teachers had selected Renée Silver.

Yet, the principal, someone whom Silver regarded as a “step below divinity,” said, “Le Maréchal would not want me to, nor would I want to give the book to someone who belongs to a race that has caused our beloved country so much trouble already. I cannot bring myself to give this to Renée.” (Le Maréchal refers to Henri-Philippe Pétain in this case).

Silver and her family continued to endure these constant anti-semitic attacks which led to Silver and her sister Edith being hidden in the vast open farmlands of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Later, she and her sister reunited with the rest of their family.

Along with Silver, her mother, father and sister finally fled to neutral Switzerland.

Since then, Silver has spoken at schools and universities throughout the country in order to educate the public about the Holocaust. Today, she resides in Garden City, NY with her two cats.

Renée Kann Silver recommended these resources to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive:

50 YEARS LATER

Renée Kann Silver with Marcel Fournier in 1990. Here she is fifty years later, visiting the farmhouse where she was hidden in Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Marcel Fournier is the son of the family that hid Silver from persecution when she was 11 years old.