Trashing the Neighborhood

Brookhaven Landfill is set to close but residents want their concerns addressed before Long Island’s waste is dumped on another community.

May 3, 2023

The Brookhaven Landfill looms like a shadow over the hamlet of North Bellport. The vast mountain of trash is surrounded by an intermediate school, a homeless shelter, a prison and residential neighborhoods housing some of the most underserved communities on Long Island.

For years residents have complained of foul odors from the site.

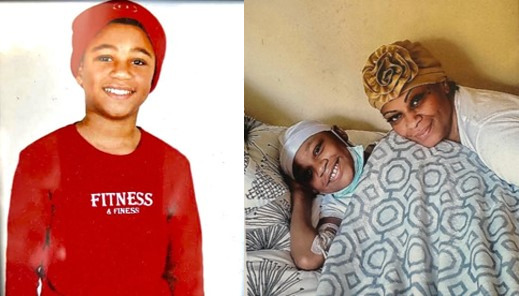

School children and teachers have fallen ill, prompting fears that hazardous waste may be to blame. A grieving mother, Nacole Hutley, is suing the Town of Brookhaven for the death of her 13-year-old son, Javien, from cancer. “My heart goes out to any human being who has to go through what we went through, what Javien went through,” she said. “Nobody should have to go through that.”

The 192-acre landfill is set to reach capacity in 2024 and is earmarked for closure. But residents say they have been fobbed off with promises to shut it down before. The site is due to stop accepting waste next year, but will continue to take in construction and demolition debris for at least two more years. Moreover, plans being developed to transfer the trash by train off Long Island could end up dumping the problem on other low-income, minority neighborhoods. Are there better solutions closer to home for disposing of Long Island’s waste?

In North Bellport and the surrounding area, community members have joined together to create the Brookhaven Landfill Action and Remediation Group, locally referred to as BLARG. They are committed to finding sustainable, grassroots solutions for the disposal of Long Island’s waste. The average Long Islander produces 4.5 pounds of municipal solid waste per day, which adds up to over 2 million tons per year. Brookhaven Landfill accepts 1.2 million tons, more than half the total.

On Earth Day, April 22, a small but vocal band of BLARG supporters marched through the neighborhood to highlight their concerns. Monique Fitzgerald, a co-founder of the group, said, “The landfill is a 270 ft grave monument to environmental injustice that has harmed the community of North Bellport and surrounding neighborhoods for almost 50 years.” BLARG is calling for an “effective clean up that restores all that has been damaged” and the introduction of zero-waste initiatives to reduce pollution.

BLARG was founded after George Floyd’s murder in 2020 and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in order to identify “systemic issues putting Black lives most at risk,” Fitzgerald explained. Concerns regarding the landfill, which stands on ancestral Unkechaug land, are focused on notions of environmental justice and systemic racism, as well as negative impacts affecting the surrounding community’s air quality, groundwater, health outcomes, education sector, economic future and quality of life.

Brookhaven NAACP president Georgette Grier-Key said after the march, “Historically the policy is to dump anything derelict, whether it is landfill or housing, with no regard to the people who live here. Our community loses life expectancy because of this.” Her comments were backed by Dennis Nix, a local activist who believes his health was undermined by working at the landfill.

“I suffer from upper respiratory illness, I have asthma and take 11 medicines daily,” Nix said. “We’re taking these actions to make sure we are heard and treated fairly.”

REMOVAL BY RAIL

The Brookhaven Landfill has been collecting Long Island’s garbage as well as construction and demolition waste since 1974. As it approaches capacity, a pressing question has emerged: where will Long Island’s garbage go?

Will Flower, senior vice president of Winters Bros. waste disposal, believes his company has the most environmentally friendly solution. Under its plans, waste would be transferred off the island by rail.

“I’m gonna get my trash geekness on, but that’s the world I live in,” Flower said. “I’m going to talk about my world, which starts at the end of a driveway when people throw their garbage out. It’s not glamorous, but it’s critically important.”

The proposed Winters Bros. rail terminal, warehouse, and recycling facility would be built on a 228-acre plot of land in Yaphank near the landfill. Thirty percent of the plot will be conserved as “green space.”

“We could get even more trucks off of the street, which would result in less air pollution and greater efficiency,” Flower said. “For every one rail car that you use, you can take five trucks off of the roadway.”

The Town of Brookhaven has determined that the proposed infrastructure will have no negative impact on the surrounding areas and environment, an initial step towards approving development. Work on the site was expected to be completed in 2023, but has yet to begin.

If the facility goes ahead, over one million tons of Long Island trash will be delivered by truck to the Yaphank site. From there, it will be transferred by rail to landfills in Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio, but this could place the burden on other low-income and minority communities.

“That’s a hard ‘no’ from BLARG and myself personally,” said Fitzgerald. Her group is in touch with one of the affected communities in Fosteria, Ohio. “We are in complete solidarity with them.”

In addition to taking in all kinds of waste, the Brookhaven Landfill accepts approximately 350,000 tons of ash per year created from three waste-to-energy facilities on Long Island, run by Covanta. The company’s plants incinerate garbage, turning it into energy, and creating ash as a by-product that needs to be deposited somewhere; that “somewhere” is the landfill.

The Winters Bros. rail system does not include a disposal plan for the ash at this time, and Covanta is still working on its plans. “We’ve made no commitments or contracts at this time,” Dawn Harmon, the area asset manager for Covanta, said. “We’re still sort of just exploring all of our options and haven’t made a final decision about how we’re going to approach disposal after [the landfill] closes.”

An active lawsuit against Covanta filed by a former employee in 2013 has amplified fears of the ash being potentially toxic. The suit alleges the ash is not treated to remove harmful chemicals and products, threatening people’s health.

Despite concerns, Harmon asserts the ash produced from their waste-to-energy process is non-toxic. “The bottom line is that no ash from Covanta’s facilities has ever been determined to be a hazardous waste,” she said.

As for ash disposal, Harmon said there are industry-wide opportunities being researched. “There are some very promising opportunities in development, both for the reuse of ash as an aggregate and as a raw material for cement manufacturing,” she said. But these initiatives are still a ways off and cannot be used to solve the impending problem of what to do with the ash.

JUSTICE FOR JAVIEN

Residents have long voiced their concerns regarding odors and emissions from the landfill, according to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Frank P. Long Intermediate School, serving fourth and fifth graders, is only a mile south of the site.

Isabella Gascon, a sophomore at Stony Brook University, attended the school from 2012-2014. She remembers the constant stench wafting through the halls.

“They shut down the school [a few times] because the smell from the dump was so bad on a hot day that it made students pass out and teachers get sick,” Gascon said.

In 2018, a group of teachers, parents and neighbors filed a lawsuit for “dereliction of duty” against the Town of Brookhaven, alleging toxins from the landfill were damaging their health. More than 30 teachers have been diagnosed with cancer since 1998, and 14 have died. “I firmly believe that if this [school] was in a different community it would have been closed a long time ago,” said E. Christopher Murray, the lawyer for the teachers and Hutley.

The stakes were raised in January of this year when Hutley announced at a press conference with Murray that she would also be suing the town. She blames pollution from the landfill for the death of her son, a former pupil at Frank P. Long Intermediate School.

Hutley’s 13-year-old son Javien Coleman passed away after a tragic two-year battle against non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma last October. Outside her home, a few streets from the school, there is a shrine to Javien. Decorated for each holiday, it is a place where the family can honor him with photos and his football jersey number #21. Inside, photographs of young Javien fill the walls and tables, keeping his memory and smile alive.

Hutley shared, “He never complained. He was such a strong individual.” Just one year after entering the school, Javien contracted this disease. He had extensive rounds of treatments, including a bone marrow transplant from his older brother. Hutley recalled how Javien was before his illness.

“He was so active, a strong little boy. There was no stopping him. He’d be outside everyday after school playing football or basketball. He loved playing [and] he loved school. He’d get up every morning early to go.”

After his diagnosis, Hutley remembers Javien investigating the history of the landfill and its dangers for himself on his computer. “It broke my heart,” she recalled. “He said, ‘If I would have known that, I wouldn’t have went to school there.’”

Cheryl Butler, Javien’s grandmother, added, “Had something been done when cases first happened, Javien would have still been here. What does it take? Another kid to die? Ten, 20 more kids to die?”

At the launch of her legal action on January 23, 2023, Hutley insisted, “The school really needs to be shut down. They are jeopardizing a lot of kids. Not just the kids but the teachers, the workers.”

Her lawyer noted that medical reports for Javien identified the presence of two toxic chemicals, Benzene and Trichloroethylene (TCE), in his body. “The type of toxins that have been found at Frank P. Long School are the types of toxins that can cause cancer,” Murray said. “Javien had no other predisposition to those types of cancer. And the type of cancer he developed is also something that is caused by environmental, as opposed to genetic reasons.”

CHEMICAL COCKTAIL

The Brookhaven community has the lowest life expectancy rate on Long Island at 73.2 years. In comparison, the average life expectancy for the whole of Suffolk County is 80.9 years. “It’s just sad. It’s one of the poorest communities on Long Island and you have no choice but to live near the dump and have a lower life expectancy,” said Isabella Gascon. However, it is difficult to distinguish the impact of pollution from other factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantage.

Based on criteria established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Frank P. Long Intermediate School does not have a statistically significant number of cancer cases, according to a 2019 health report by the New York State Department of Health, which looked at cases from 2004 to 2017.

Air sample tests were also conducted by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) to determine whether there were above-regulation levels of toxins at the school. The presence of long-term, including several carcinogenic, gases were found, as shown by the pie chart below. Individually, these carcinogens were not at high enough levels to cause concerns, according to NYSDEC.

However, chemical toxicologist Dr. Harold Zeliger believes the state is looking for answers in the wrong direction. “There are a large number of chemicals in that landfill,” he explained. “When you have low levels [of chemicals] causing problems . . . then you look for mixtures. And we have an incredible mixture here.”

Zeliger added, “A given chemical would not necessarily cause cancer or cause any respiratory effects. When mixed with other chemicals [it] indeed can cause such effects.” He believes a public health survey is needed to determine if people living close to the Brookhaven Landfill are experiencing more health side effects than those living elsewhere. “You have to look at it as a public health issue,” he said.

RACE AND WASTE

Brookhaven is not the first town to experience these problems. In 1982, residents of Warren County, North Carolina, a predominantly African-American community, joined together to oppose a landfill contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) near their homes. Their protest gave birth to the environmental justice movement.

After lawsuits and public hearings were not enough to prevent the landfill from opening, over 130 people marched two miles from Coley Springs Baptist Church to the site. There were 55 arrests on the first day, but they continued their fight for six straight weeks.

This led to a ground-breaking 1987 report by the United Church of Christ, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, which coined the phrase “environmental racism.” It found “race to be the most potent variable in predicting where these facilities were located—more powerful than household income, the value of homes and the estimated amount of hazardous waste generated by industry.”

The report set out a framework designed to protect workers, communities and ecosystems that remains relevant to the alleged pollution affecting the Frank P. Long Intermediate School and surrounding area.

“The environmental justice framework rests on the Precautionary Principle for protecting workers, communities and ecosystems,” it stated. “The Precautionary Principle asks, ‘How little harm is possible’ rather than ‘How much harm is allowable?’”

Twenty years after the original report, a follow-up study was commissioned, Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty, which revealed “racial disparities in the distribution of hazardous wastes [were] greater than previously reported.” According to Robin Saha, a principal author of the 2007 report, people of color had been “left-behind” by a combination of “redlining” and “historic white flight from the cities.

“These were places where industry found it easier and cheaper to set up waste facilities, because of the lack of strong political opposition that you might get in the suburbs or in wealthier areas.”

Saha said he was “surprised” the same patterns persist today. “In fact, they seem to have gotten a little worse,” he said. “I had expected that the environmental justice movement would have been pushing back on siting new facilities near Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) communities.”

OUTRAGE IN OHIO

The Sunny Farms Landfill in Fostoria, Ohio is one of the destinations set to receive Long Island’s waste after the closure of Brookhaven Landfill. Residents of nearby communities are frustrated and worried about the potential harm Long Island’s garbage will bring. The Ohio landfill already handles large volumes of waste from other areas.

“We currently bring in 7500 tons a day by rail from out of state, and our own local waste accounts for only 2% in our landfill…They [local government] want to expand to 12,000 tons a day — making us the largest landfill in the country,” said Lora Wolph, a member of the Greater Fostoria Environmental Coalition. “Our community will collapse if this doesn’t stop.”

She added, “We get contaminated soil, industrial and residual waste, toxic ash, medical waste, sludge, automotive fluff, and construction and demolition mixed with municipal solid waste. The gypsum drywall led to extremely high levels of hydrogen sulfide that led to illness and inability to go outside for years.”

The group has created a Facebook page dedicated to airing complaints and other dirty laundry related to the garbage dump. “The contaminate in the air has a smell that is reminiscent of burnt matches and burnt plastic,” Karl Walter posted on Facebook in 2021.

“I would like nothing more than to open a window and to take in some fresh air. That is if there was any fresh air outside to be had,” he continued.

Other groups with similar concerns have emerged: Citizens Against Lafarge’s Lordstown Landfill (Warren, Ohio), Ditch the Dump (Hamilton County, Ohio) and the Ohio Solid Waste Caucus. The East Palestine train derailment in February, which sent residents fleeing from toxic chemicals, has added to their concerns.

“Leaking railcars travel through our towns every day with little to no daily oversight,” Wolph said. “All they need to do is decrease the allowed daily tonnage to a reasonable amount and we’d have plenty of capacity for the small amount we produce locally.”

GARDEN FOR GROWERS

Aside from sharing the group’s collective voices and concerns, BLARG members founded a compost garden in 2021 in the center of North Bellport, approximately four miles from the Brookhaven Landfill. In the community garden sit several garden beds, a space for children to tinker with outdoor toys, a set of benches, tables and chairs, as well as their compost plot.

A community compost garden can help educate residents about sustainable living by providing a tangible example of how composting can benefit the environment. “We’re encouraging people to learn how to compost to reduce the products being dumped in the landfill, but also to enrich our community by planting fruits and vegetables,” said Khadijah Yanni, a member of BLARG. The local area lacked nutritious stores and was a “food desert” for healthy produce, she added.

The community garden started as a 90-day pilot program called the Anti Landfill Composting Collective, or ALCC, for the summer. In just a single summer, the community collected and composted 1,300 pounds of food scraps from 20 families. The garden is set to open for the Spring/Summer season on May 13.

The advantage of community composting is that it can help to reduce the amount of organic waste in landfills by providing space for local residents to compost food scraps, yard waste and other biodegradable materials. Composting creates a nutrient-rich soil amendment that can be used to grow healthy plants. And by using this soil instead of synthetic fertilizers, the community can reduce its reliance on non-renewable resources and decrease the amount of waste generated by synthetic fertilizers.

When organic waste decomposes in landfills, it releases methane, a potent greenhouse gas. By composting this waste, the community can also help to reduce the amount of methane released into the atmosphere, mitigating the impact of climate change.

“We have to change our culture,” Monique Fitzgerald said. “Right now we have a throwaway disposable culture where we produce waste with no plans for where it’s going to end up.”

‘A CONCEPT OF THE PAST’

In recent years, waste management has become a growing concern for many communities around the world. As landfills reach capacity and the impact of waste on the environment becomes increasingly evident, people are searching for new ways to dispose of their trash.

New York is trying to clean up its act. Every ten years, NYSDEC publishes a solid waste management plan. The most recent draft was published in April and is out for consultation until May 15. At its launch, David Vitale, division director of materials management at NYSDEC, boldly declared, “Waste is a concept of the past.”

One of the state’s goals is to pressure local administrations to develop a more circular economy and encourage extended producer responsibility, shifting responsibility for reducing waste, such as plastic, on manufacturers rather than consumers. But Vitale admitted, “The primacy for solid waste management rests with local governments. We are a home-ruled state. That’s how the laws are set up; That’s where the authorities are. The state doesn’t have that particular authority.”

With the Brookhaven Landfill set to close, Long Island’s nearly two million population is left to find an alternative waste management solution. The Town of Brookhaven, which has a gross annual revenue of over $60 million from the landfill, declined requests to comment on this article.

However, in February this year the town signed a 20-year lease with Coast Energy, a private developer, for the right to place 16,000 solar panels on 35 acres of capped landfill. Town Supervisor Ed Romaine claimed it was “a big step” towards creating an energy park.

Anaerobic digesters present another potential way forward. These mechanisms break down food waste and other organic matter, turning them into natural gases. The process would be beneficial to the environment not only as a means of recycling food waste but also as a provider of renewable energy. American Organic Energy began constructing an anaerobic digester in Yaphank in 2022, but it is not open for use yet.

Currently, none of the proposed solutions satisfy the local residents’ expectations. “I have been doing some research on other localities throughout the United States,” John McNamara, a Brookhaven resident and environmental activist, said. “We’re so far behind on the island. I think we need a whole different stance, our recycling rate is pathetic.”

DOWN TO ZERO

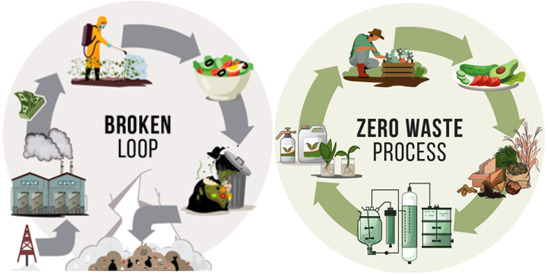

The concept of zero waste solutions has emerged as a promising option for many communities struggling with waste management issues. Zero waste is a circular approach that aims to reduce waste and eliminate the need for landfills by focusing on source separation, composting, and recycling.

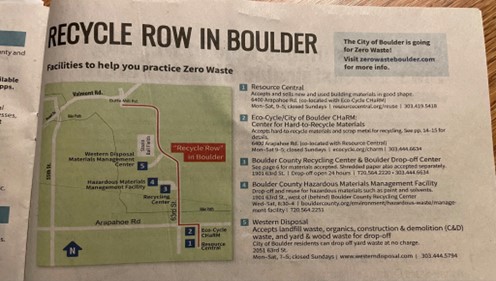

One community that has successfully implemented zero waste solutions is the town of Boulder, Colorado. The town had been struggling with waste management issues prior to the installment of Eco-Cycle, one of the nation’s oldest and largest nonprofit recyclers. Today it recycles and composts more waste than any town in Colorado and claims its lower emissions are equivalent to taking 28,000 cars off the road each year.

“Boulder passed a zero waste ordinance in 2010,” Frances Greene, a Boulder resident, said. “The city estimates that they’re diverting about 35% of waste from the landfill.”

In efforts to adhere to the zero waste ordinance, the city set up a comprehensive source separation system, providing separate bins for different types of waste. They also implemented a curbside composting program, which encouraged residents to compost their food waste.

Western Disposal, a waste collection company based in Boulder, collects trash, recycling and compostables. “When you sign up, they ask what size container you need for your trash, what size of container you want for recyclables and what size you want for compostables,” Greene said.

“There are multiple waste collection companies, but probably 70 or 80% of all the trash [in Boulder] is picked up by Western Disposal,” Greene said.

The company rolls out newsletters seasonally that include educational information and tips for residents who receive their services.

Perhaps most importantly, the community in Boulder has become more engaged and involved in waste management. Residents are more conscious of their waste and are taking steps to reduce it. Businesses are also becoming more sustainable, as they seek to reduce their waste and find ways to repurpose materials.

“I got their largest big bin for compostables, because I was going to do a lot of gardening,” Greene said. “I got their very smallest one for trash.”

Greene’s daughter, Jennifer, lives in Brookhaven. While in graduate school, Jennifer Greene worked at Recycle Ann Arbor in Michigan, where she noticed that residents eagerly cooperated in recycling initiatives. She would like Long Islanders to follow their example.

“The infrastructure was there for people to participate,” Jennifer Greene said. “Here there doesn’t seem to be public education going on. There don’t seem to be high rates of participation, the infrastructure isn’t really there to facilitate it.” That was “really discouraging,” she added.

Other cities have established their own plans for zero waste. The state of Colorado aims to recycle 35% of its waste by 2026 and 45 per cent by 2036. Boulder’s success has attracted attention from other communities struggling with waste management issues, which are looking for a model for how to implement zero waste solutions in their own towns and cities.

John McNamara spoke at a Brookhaven Town meeting in February 2021 about the example of Colorado Springs, which has a historically low recycling and composting rate of 15%, half the national rate of 32%.

However, the town has set up a recycling center which collects and sorts recyclable materials such as metal, plastic, and glass. The materials are then sold to local businesses to be repurposed into new products.

From this, McNamara discovered the landfill in Colorado Springs has been able to extend its life as the surrounding community implemented a recycling program featuring three different recycling systems, a program he felt could work in Brookhaven.

To begin a successful shift towards environmental conservation and preservation, McNamara believes the town must be educated first.“You have to educate the community and get them ready for this [change],” he said. “Things can be done in terms of legislation, but you have to work on the education piece.”

FIXING THE BROKEN LOOP

Scientists are also working on eliminating waste. A team of researchers, led by Benjamin Hsaio from Stony Brook University and The University of Queensland, have begun a project centered on low-cost zero waste technology. Although not yet complete, their project Nature-based Nanomaterial for Solutions to Climate Change aims to help farmers and local communities to combat climate change and enhance food-water-infrastructure security by transforming organic waste into high value products.

Credit: National Science Foundation/Benjamin Hsaio

Their plan will make use of underutilized agricultural waste, recycled papers and boxes, and food waste to create a new kind of nanocellulose-enabled bio-nano fertilizer for agricultural applications as well as biogels for infrastructural protection and reduction of the impact of drought. Through this project, the team will advance zero-waste technology.

As waste management continues to be a pressing issue around the world, it is clear that zero waste solutions can bring significant benefits to communities. By adopting a circular approach that focuses on source separation, composting, and recycling, communities can reduce waste, save money, and create a more sustainable future for themselves and the planet.

WASTED POTENTIAL

Many questions remain about what life will look like for local residents after the official closing of the Brookhaven Landfill. The Town of Brookhaven, industrial companies, and community activists have all taken steps to achieve what they see as the ideal outcome, but roadblocks still stand in the way.

Residents remember promises made about the landfill when it was first opened 50 years ago.

“I was shocked when I read the old 1970s newspaper articles about the plans for this new landfill to be opened and how and what was promised,” Jennifer Greene said. “‘It’s going to be a beautiful park with ski slopes:’ I heard people refer to that and I thought, ‘oh, you must be exaggerating.’ No, they really said they would turn this landfill into a beautiful park after it’s closed.”

There is no park in sight, only the mountain of Long Island’s waste and the communities in its shadow.

Margot Garant • May 11, 2023 at 11:50 am

This article is poignant, informed and the writer presents a very complicated issue with the ease of penmanship! BRAVO! Now let’s get the same result from a comprehensive new GREEN PLAN for managing Brookhaven’s waste!

John McNamara • May 5, 2023 at 1:55 pm

Excellent and very comprehensive presentation of a complicated subject! Well done!